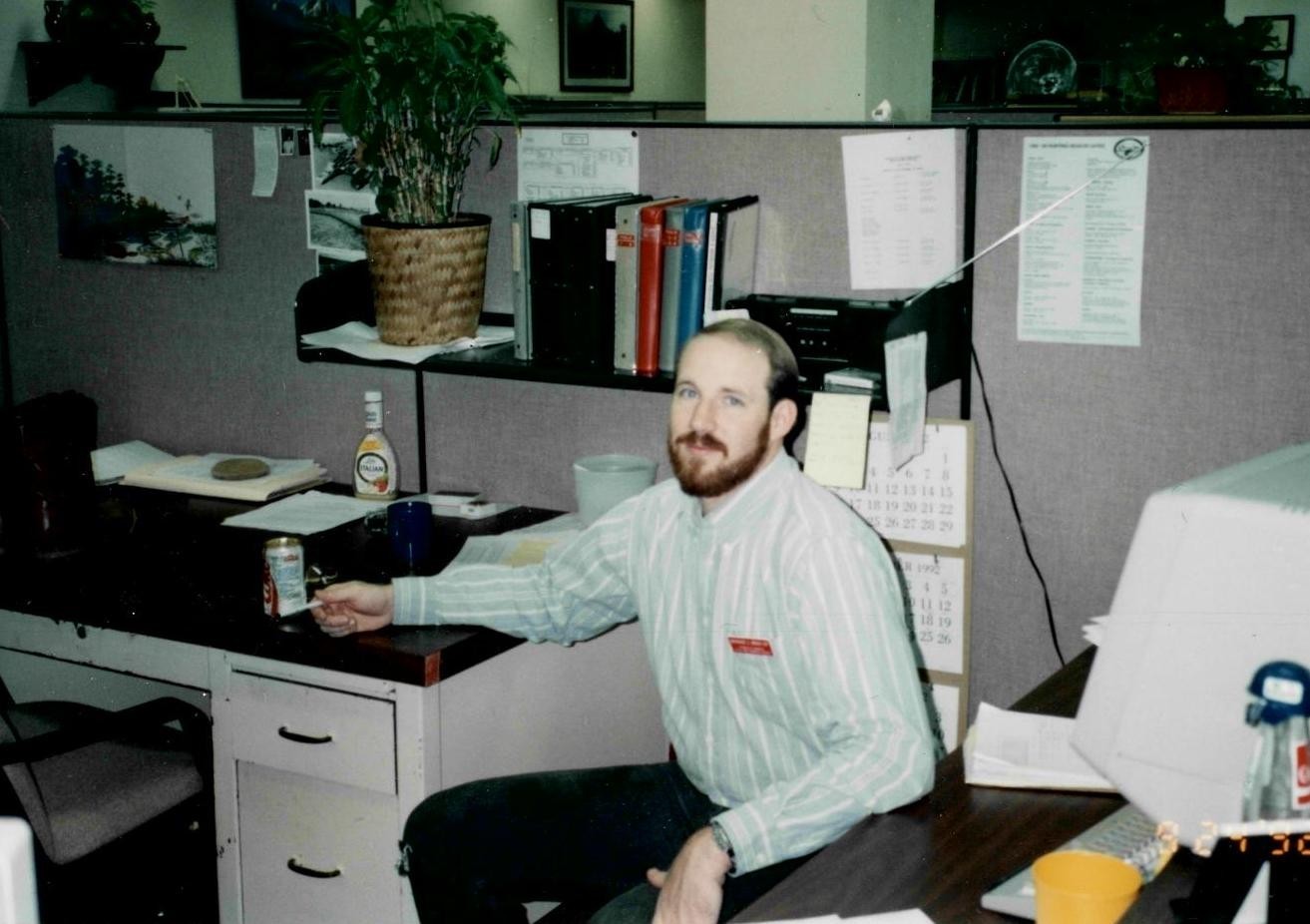

If you’ve ever spent five minutes with Mike Biggs, you learned two things almost immediately: he cared about people and he took the mission seriously. That combination shaped a 38-year career with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, defined not just by technical excellence but by steady leadership and a genuine commitment to the teams and communities he served.

Biggs never fit the quiet-engineer stereotype; a fact colleagues noticed almost immediately.

“Being an extrovert is kind of weird for an engineer,” he said with a laugh. “That’s why I know what everybody else’s shoes look like!”

That quick humor, paired with an approachable style, was part of how Biggs connected with the people around him.

For him, engineering was never just about numbers and plans. It was about responsibility, relationships and showing up for the people who depended on the work, all qualities colleagues say they will remember most.

A Career That Started with Family

Biggs’ career with USACE began not with a long-term plan, but with a family decision that changed everything.

After graduating from Louisiana Tech University in 1987 with a degree in civil engineering, Biggs accepted a job in Houston, Texas. Shortly afterward, his grandfather suffered a stroke. Living in Little Rock with Biggs’ grandmother, he needed care and Biggs’ parents asked if he would consider coming home to help.

So as any good son would do, he declined the job offer in Houston, applied to the Little Rock District and was hired.

“That’s how I ended up in Little Rock,” he recalled. “And that one decision turned into a 38-year career.”

Finding His Own Way as a Leader

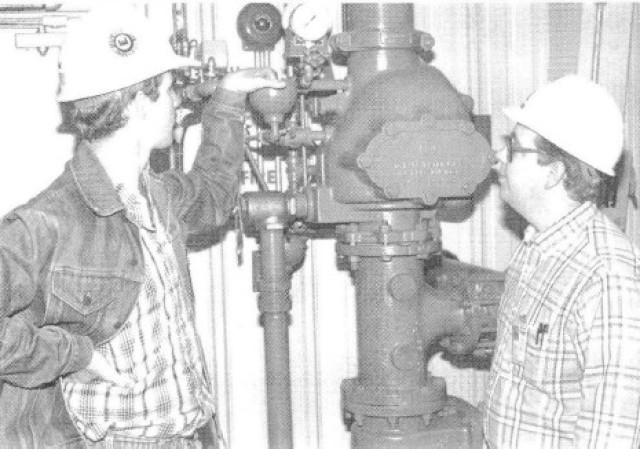

Biggs had already worked as a student aide in the Geotechnical Branch during the summer of 1986, but becoming a permanent employee the following year came with a steep learning curve. When he was first hired, the workplace culture looked very different than it does today. There was a level of hazing that felt almost military in nature, and at times it could be rough for someone just starting out in their career.

That early experience shaped Biggs’ leadership philosophy for years to come.

“Going through that, I decided right then that was not the way I wanted to do things,” he explained. “I wanted to mentor my team in a different way.”

From that point on, Biggs became a firm believer that mentorship is not optional and that leaders have a responsibility to support and develop their teams in a healthy way. That belief was reinforced over time by mentors such as Henry Himstedt, Jorge Gutierez and Marty Hammer who helped guide his growth as a leader.

Later in his career, Biggs spent time in project management, what he jokingly refers to as “the dark side.” That experience broadened his perspective beyond technical work.

“I learned a lot,” he reflected. “I got to see the kinds of positive team interactions that created a well-rounded and successful product.”

Biggs credits Himstedt, Hammer and Gutierez with helping shape his leadership approach and reinforcing the importance of collaboration, communication and respect, values he carried with him when he returned to the Hydraulics & Technical Services Branch and eventually became branch chief.

A Career Defined by Breadth and Impact

Over the years, Biggs worked across nearly every corner of the district. His career included time in Geotechnical Engineering, Project Management, Reservoir Control, Planning and Hydraulics and Hydrology. Along the way, he contributed to major efforts such as the Dark Hollow Study, the White River Minimum Flows Study and portions of the Montgomery Point Lock and Dam construction.

In 2015, Biggs became chief of the Hydraulics and Technical Services Branch, completing a journey that began as a geotechnical intern and evolved into leading one of the district’s most critical technical teams.

When Biggs reflects on his career, the White River Minimum Flows project stands out as one of his most defining accomplishments. The effort was complex, controversial and required years of persistence through an intense federal approval process.

“At first, I didn’t think it made sense,” he admitted. “As a flood fighter, it just didn’t make sense to me.”

However, as the planning process moved forward, the data consistently told a different story. The project proved beneficial both regionally and nationally and did not compromise USACE’s flood control mission. Still, securing approval was far from easy.

“At the time, a lot of people tried to kill the project including the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works,” Biggs said. “We used to jokingly call him ‘Dr. No’, because his job was to say no,” he laughed.

All joking aside, Biggs was quick to add that the role of ASACW carried enormous responsibility.

“In all seriousness, they have a very hard job,” he noted. “They’re implementing the will of Congress and the administration and that means carefully vetting special funding projects like minimum flows.”

Despite the challenges, the team continued to push forward. They believed in the work, in the numbers and eventually got it approved.

Looking back now, Biggs says the project exceeded expectations.

“It did everything and more than it was supposed to do,” he said. “I’m really proud we stayed the course.”

While continuing to learn and grow throughout his career, Biggs also volunteered for emergency response missions, deploying nationwide to support hurricane and earthquake recovery efforts.

“When USACE shows up, the big red castle is a source of comfort,” he said. “People know things are going to get done.”

Biggs acknowledged that supporting deployments can be challenging, particularly when team members are away for 30 to 60 days at a time. However, he viewed the experience as invaluable.

“Employees come back with new skills and strong working relationships with people from other districts,” he said. “That experience matters.”

Jim Marple, chief of emergency management for the Little Rock District, said Biggs has been someone people could always count on not just as a leader and problem solver, but as a great friend.

“Mike was never one to shy away from speaking up when it mattered and always brought clarity and common sense to even the toughest situations,” Marple said.

Managing Water When There’s No Easy Answer

For Biggs, the most rewarding part of leading the Hydraulics & Technical Services Branch was watching his team navigate increasingly complex and high-stakes water management decisions during an era of unprecedented hydrologic extremes.

During his tenure, the district experienced repeated major flooding events along with periods of flash drought. Across those conditions, the branch was responsible for balancing flood control, hydropower, recreation, drinking water supply and environmental considerations… often simultaneously.

“There’s no free chicken,” Biggs explained. “If you want more water for one purpose, it has to come from somewhere else.”

Biggs said the challenge, and reward, came from seeing his team master water control plans and apply them across a wide spectrum of operating conditions, while carefully weighing long-term impacts and unintended consequences.

One of the most significant efforts during that time was the implementation of an interim risk reduction measure at Beaver Lake, which Biggs said affected the entire White River system. The measure blended best practices from more than 50 years of operation, drawing from water control plans approved in 1966 and 1998, and moved the district toward a more risk-based decision model.

Despite the growing demands and competing interests, Biggs said the district successfully managed the full range of conditions these projects can face.

“We’ve handled huge floods and droughts with no dam failures and no unplanned deviations,” he said. “That’s a credit to the people doing the work every day.”

Even after decades of flood response and emergency operations, one moment still stands out.

“The Gate 20 issue at Dardanelle scared me more than anything else in my career,” he said.

Faced with a problem they had never encountered before, the team worked in real time to find a solution, securing the gate within 36 hours and avoiding impacts to Arkansas Nuclear One, Clarksville’s water supply and navigation.

“The team did a stellar job,” Biggs said. “I couldn’t have been prouder.”

Advice He Hopes Sticks

Biggs encourages the next generation of engineers to approach their work without fear of mistakes, emphasizing that growth comes from trying, learning and accepting constructive feedback.

One experience early in his career left a lasting impression. After completing a design for a slack water harbor at Russellville, the project was returned by the ASACW.

“I’ll never forget it…Dr. No sent it back and said it was over designed, and it wasn’t right,” Biggs recalled.

At the time, clear guidance did not exist, so Biggs based the design on what he believed was the best solution. His supervisor, Ken Carter quickly identified the issue and told him it needed to be corrected.

“Ken got chewed out by the ASACW, but he never blamed me,” he said. “He told me it was their job to challenge the work and that my calculations were sound and reproducible, even though the design wasn’t right for that particular project, and he stood by that.”

Biggs said the experience reinforced an enduring lesson.

“As long as you’re being ethical and following sound principles, whether you’re building a budget or designing a dam, don’t be afraid to act,” he advised.

He credits that mindset with fostering a culture where innovation could thrive. During his tenure, the H&H office produced three USACE Innovator of the Year award recipients, a headquarters-level honor Biggs attributes to a team that felt empowered to try, learn and improve.

Edmund Howe, chief of the H&H section attributes much of his own success to Biggs’ leadership.

“I owe a lot to Mike, he not only took a chance giving me the keys to his H&H shop, but he also told me to drive fast and take chances,” Howe said. “Mike led with trust and a sense of humor, and we always discussed differing or similar perspectives respectfully.”

Howe credits Biggs' unwavering confidence in his ability to weigh different options in decision-making as a key factor in reshaping his outlook, both professionally and personally.

Looking Forward, Not Back

As he heads into retirement, Biggs is looking forward to becoming a master gardener. He credits fellow Little Rock District employee, Cherith Beck, for guiding him along the way, jokingly referring to her as his “organic sensei.” He is also looking forward to exploring beekeeping, joining the Arkansas Apiary Society and spending more time with his family and grandchildren.

Most of all, he’s ready to let go of watching the radar.

“I don’t need to worry about when it’s raining anymore,” he said. “The team’s got it from here.”

Reflecting on his career, Biggs sees stepping aside as the final responsibility of leadership.

“I’m now the least qualified guy who walks into the room…and that’s exactly how it should be. It’s time for the next generation.”

Social Sharing