VIEW ORIGINAL

Enduring hardship is intrinsic to life for the few who serve in the Infantry. Tackling demanding challenges and persevering through discomfort initiate a distinct sense of accomplishment. Motivated by this mindset, we set out to climb Mount Denali, continuing the U.S. Army’s legacy on North America’s tallest peak. The relationship was first forged in the 1940s while testing equipment under extreme conditions, enlisting experienced climbers such as Bradford Washburn to contribute their expertise. From the 1970s to present, the U.S. Army’s Northern Warfare Training Center (NWTC) sent expeditions consisting of instructors and Soldiers from Fort Wainwright, Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, and foreign militaries to test equipment and build confidence in cold weather and mountaineering proficiency. Beyond testing our resolve, we sought to apply knowledge acquired during military mountaineering courses at NWTC and Army Mountain Warfare School (AMWS), as well as operational experience of the 1st Infantry Brigade Combat Team, 11th Airborne Division, which included recent Joint Pacific Multinational Readiness Center (JPMRC) rotations. This article presents a comprehensive account of our preparation for and successful completion of the ascent.

The “Delta Alders” Training Strategy

As snow and clouds finally dissipated at our 9,717-foot camp on the Kahiltna Glacier, climbers from Valdez, AK, stopped and noticed our Delta Alders logo. To our shared amusement, they thought we were out of our minds when we said we recreate in the Delta Range. The Deltas offer accessible climbing, skiing, and snowmachining to the Fairbanks community. However, the range is known for unique challenges presented by dense alder groves, a variable continental snowpack, and isolation. In contrast, Alaska’s coastal mountains are popular for backcountry skiers due to their favorable snow conditions and dependable avalanche forecasts.

The Delta Mountains are on the eastern terminus of the Alaska Range, while Denali is part of the Central Alaska Range. The two ranges differ greatly in altitude and access. The highest peak in the Deltas is Mount Kimball at 10,300 feet, and most of the western glaciers are within a mile of the Richardson Highway. The Delta Range served as the perfect training ground for our expedition because of access, glaciology, avalanche considerations, weather challenges, and beginner-to-advanced climbing options.

1. Team Fitness and Dynamic

Aerobic fitness training is among the most important components of a successful climb. After years of physical readiness training (PRT), we focused on a training regimen parallel to that found in Training for the Uphill Athlete by Steve House, Scott Johnston, and Kilian Jornet. High-repetition strength training, coupled with endurance and climbing drills, led to routine circuits aimed at maintaining target heart rates and minimizing lactate thresholds and acidic effects in muscle. Although many Army leaders thrive at interval heart-rate training, this would not maximize performance. The five pillars of Holistic Health and Fitness remained at the forefront. Physical, nutrition, spiritual, mental, and sleep readiness proved critical in all aspects of pursuing Denali.

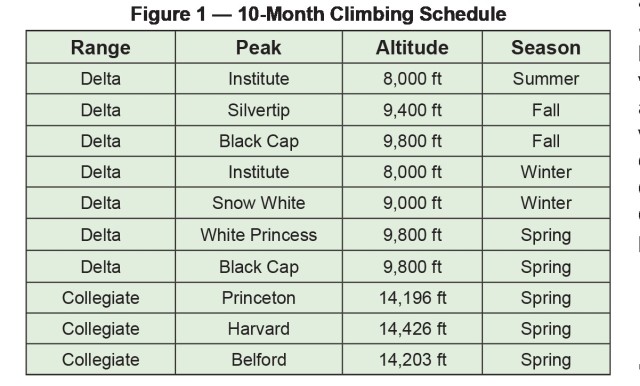

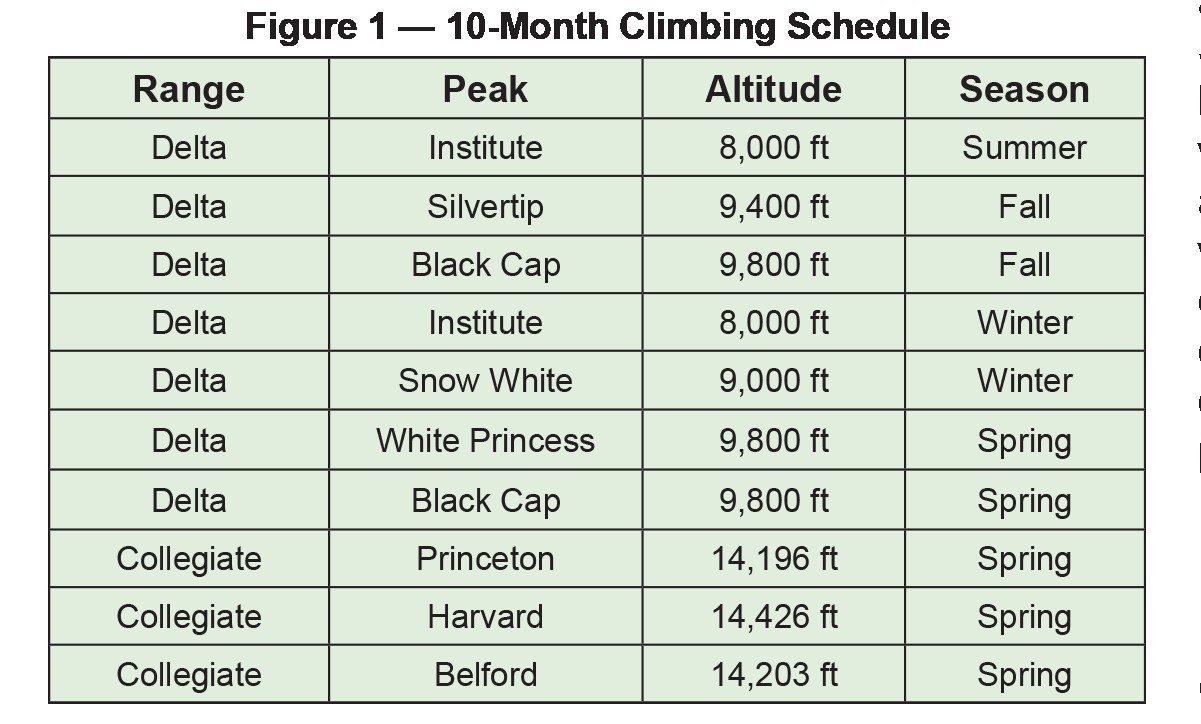

Our team training plan encompassed countless hours of high mileage in extreme conditions to overcome any obstacle encountered on Denali. We accomplished 10 training ascents, including a 22-hour trek of skiing and climbing on Snow White. Throughout training we kept pack weight at less than 30 percent of body weight and decreased sled weight according to the steepness of the incline, whether ascending or descending. Selecting dependable partners was critical, as you rely on each other for safety and sanity during demanding weeks roped together. Skiing with a sled on a rope team requires practice as each tug of the harness or slack caught beneath a ski can challenge even the most patient individuals.

2. Decision-making and Navigation in Poor Weather and Glaciated/Avalanche-Prone Terrain

The Deltas did not disappoint, with white-out travel on the Gulkana, Canwell, and Castner glaciers in addition to climbs through intermittent clouds. High winds forced us off Black Cap just 1,000 feet from the summit and kept us shoveling out our tent during -35-degree Fahrenheit (F) wind chills on Gulkana. Navigating through broken glaciers and around unstable icefalls demanded caution as we carved our path across the contours of Snow White. Avalanche activity and hair-raising “whoomphs” led us to turn back early from White Princess, while steep, icy couloirs on our second climb of Black Cap warranted solid climbing techniques and protection on the final ascent. This experience prepared us to navigate similar terrain and weather decisions on Denali.

3. Climbing and Skiing Techniques

We practiced crevasse rescue, injured climber descent, and fixed-line setup on gentle terrain near Fairbanks before moving to the mountains. We took advantage of skiing areas available at Fort Wainwright on weekly 10-15-kilometer ski trips with heavy packs and sleds to prepare ourselves mentally and physically.

4. Winter Climbing and Bivouacking on a Glacier

Climbing trips emphasized camp routines like probing, cache marking, building wind walls and other essential duties. Our experience in 1/11 IBCT (Arctic Wolves) provided extensive cold weather training each year, starting with introductions for new Soldiers and refreshers for seasoned ones. Training included collective live fires, a brigade field training exercise (FTX), JPMRC rotations, and activities such as snowshoeing, skiing, biathlons, snowmachine and Cold Weather All-Terrain Vehicle (CATV) driving, Arctic Winter Games, and the Polar Plunge through the winter season. These were combined with weekend Delta climbs in the winter months to prepare for extreme cold.

5. Altitude Acclimatization

We chose not to acclimatize before climbing Denali, since any benefits would deteriorate by the start. Instead, we relied on a well-planned ascent and sought to test this approach and assess our reaction to high altitude during the train-up. We chose Colorado for high-altitude training due to its accessible 14,000-foot peaks. Starting in Leadville at 10,000 feet and climbing the Collegiate Peaks provided ideal conditions. We completed several day climbs and a multi-day trip, camping at 11,000 and 13,000 feet. In contrast, reaching similar altitudes in Alaska would require planning another expedition involving travel to a remote location with significant glacial and avalanche hazards.

6. Training Reflection: What to Add?

While all team members had experience with snow shelters, we did not practice camping in one together during training. Severe storms may damage tents, and the hard-packed snow on the upper mountain makes it essential to understand how to construct different types of snow shelters.

Equipment and Logistics

The Delta Alders team learned early on in our training that equipment and logistics were key components to success on Denali. All members had read about expeditions in the past that ended in catastrophe due to poor logistics or the use of incorrect information. This is the moment we learned the phrase, “You don’t climb your way up Denali, you camp your way up.”

We thoroughly analyzed trip reports from previous NWTC expeditions, memoirs from notable Denali expeditions, NWTC handbooks for cold weather operations, podcasts, and our own experiences above the Arctic Circle. Meticulous research built our model for calories expended and consumed daily, the quantity of water necessary to sustain exertion at high altitude, and substitutes to reduce bulk and weight in our sleds.

Food and Fuel

When we weighed in at Talkeetna Air Taxi Service, our equipment totaled 540 pounds, which equaled to 180 pounds per person that was distributed among sleds and packs. This was significantly more weight than other teams on the mountain and provided us with 30 days of food and fuel instead of the common 21 days. We calculated our fuel consumption rate while ascending, which totaled 5.2 oz of fuel per person per day (15.5 ounces per day for the team). We brought four gallons of fuel which could support 33 days on the expedition based on our consumption rate. We ultimately consumed 264 ounces over 17 days, with 248 ounces or 16 days of fuel remaining.

We determined that a 4,000-calorie intake daily would sustain us for the entirety of the expedition, including the more strenuous days. Our training trips demonstrated that the team favored morning and evening meals with larger snacks for lunch. The team experimented with suggested snacks, finding that hard breads like bagels are preferable as they do not freeze easily. Dehydrated meals supplemented with oils, dehydrated cheese, and bacon bits accounted for most meals. The additives allowed for more texture and calories at a minimal weight. CPT Kwait experimented and prepared “team meals” to help raise morale and increase calories at key points during the climb. These meals were pre-packaged or frozen regular meals like spaghetti and meatballs, pizzas, pancakes, and stir fry, to name a few. The eight team meals over the course of our ascent proved critical to our diet and sanity. It broke the monotony of dehydrated meals and improved our nutrition.

Kitchen

We used an MSR XGK stove along with an MSR Whisperlite for summit day to assist the XGK in boiling water at high altitude. This addition decreased our boiling time from 40 to 25 minutes at 17,000 feet. We brought one spatula, a 2.5-liter pot for daily use, and 4-liter pot for large meals. Two of our favorite pieces of gear were the cleaning brush/soap bottle and compact kitchen sink, which made cleaning and sanitizing our kitchen extremely easy. We could thoroughly wash kitchenware with ease and dump gray water outside with no mess.

Over-Snow Mobility

We decided to use skis instead of snowshoes for our ascent up Kahiltna Glacier, since years of training taught us the motion of skinning with a sled would be more efficient and natural. All team members had experience skiing and felt confident in our ability to ski as a rope team. For the expedition, we used skis that provided us with the most options, including warm AT boots, full length skins, optimum flotation, and control.

Finally, our standout gear was our Acapulka Delta sleds. These sleds are made from Kevlar composite which drastically reduced weight while retaining durability. The sleds came with a built-in, waterproof canvas cover, and full-length zipper making access and gear organization easy in harsh weather. The rigid poles and runners allowed the sled to track behind the skier and float on powder instead of bogging down in deep snow.

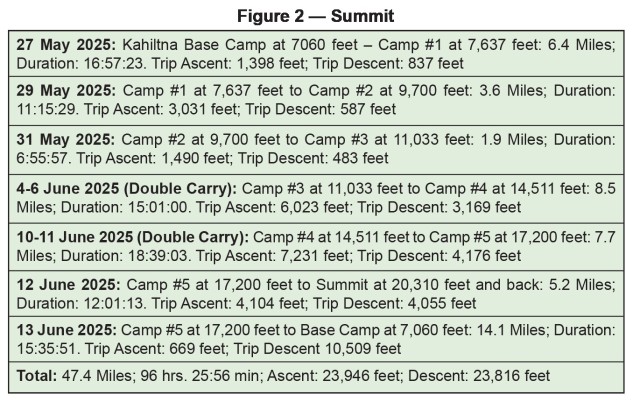

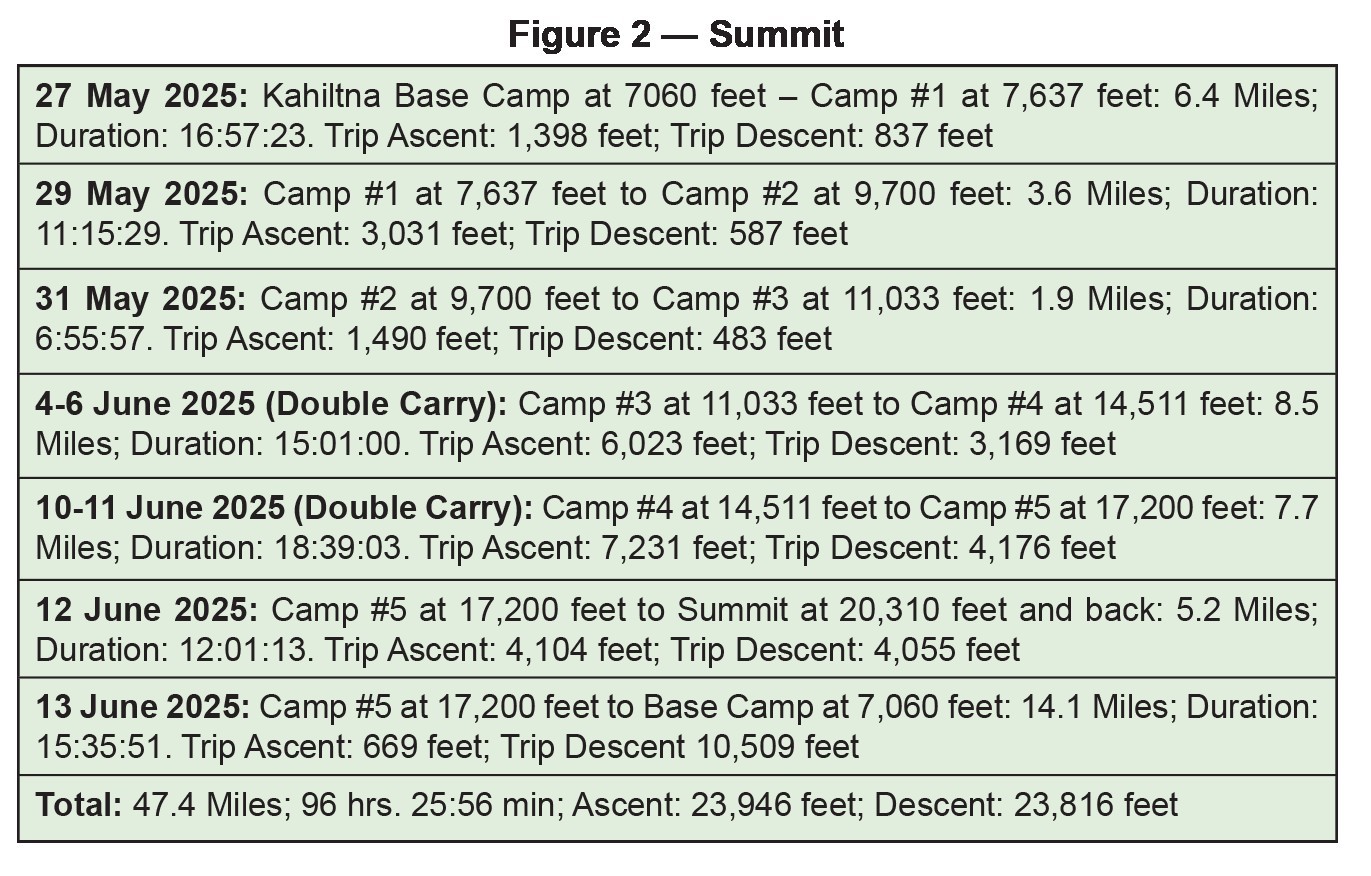

Regardless of preparation, we experienced challenges along our journey from the lower Kahiltna Glacier at 7,060 feet up to the summit at 20,310 feet, and the 14.1-mile trip back to base camp.

The Summit

Base Camp to Camp #1

After a surreal flight into the lower base camp, we were greeted with warm conditions and poor visibility. We chose to move during the night and early morning hours to begin our trek, avoiding the peak hours of solar exposure on the glacier and minimizing the risk of snow blindness, sunburn, and overheating. We immediately completed the first leg (6.4 miles) in 17 hours with an ascent of 1,398 feet and descent of 837 feet.

Throughout the 16-day expedition, the snow and ice conditions challenged our team as we skied while towing a heavy sled. The steep slope and sea of cavernous holes that could swallow a person without hesitation were not obstacles to underestimate. Being roped is hard enough while wearing crampons, let alone skis and sleds that force the body to bend and bow like an accordion. It became clear that glissading would be a crucial discipline, especially during night and early morning travel when a crisp, hard crust covers the snow. Patience and temperament proved critical for our team to be successful.

As we established Camp #1, elation set in that we had progressed beyond those at base camp. Weather reports continued to display mild temperatures but poor visibility. Navigational wands littered the route, but our team had confidence in our primary navigator (CPT Kwait). While facing terrible whiteouts in the Deltas, we pulled together to conduct proper situation analysis and make joint decisions to move slowly and safely to succeed in our efforts.

Camp #1 to Camp #2

On 29 May, the team moved from Camp #1 to Camp #2, covering 3.6 miles of glacier in 11 hours and 15 minutes to reach 9,700 feet. However, adverse weather conditions crippled efforts for days. Alpine team members must quickly grasp their camp duties, roles, and responsibilities. When on a mountain like Denali, misunderstandings, errors, or failing to fulfill responsibilities can jeopardize the entire team’s safety. Snow accumulated quickly while we set up camp, but we maintained our composure despite these conditions. All three of us had completed the U.S. Army Ranger Course so discomfort was nothing new. Being stationed at Fort Wainwright had also exposed us to similar challenges.

Following the principles ingrained through challenging Army experiences, we dug out camp five to six times a day during the bad weather. Several days passed until we glimpsed the surrounding terrain and realized our camp was too close to a dangerous headwall of heavy ice and snow from a nearby Bergschrund. When possible, we needed to move to our next destination, Camp #3.

Camp #2 to Camp #3

On 31 May, Team Delta Alders arrived at Camp #3 (11,033 feet). We traveled a difficult 1.9 miles for seven hours, towing sleds with weights up to 168 pounds across slope angles as high as 42 degrees. Camp #3 witnessed a considerable low-pressure weather system that moved in from the nearby Bering Sea. Historically, the worst storms in Denali’s history began with similar low-pressure systems competing with high-pressure systems, which built perfect storms for deadly alpine conditions. Extreme winds can cripple movement, disabling acquisition of shelter, fuel, rations, and even water.

Camp #3 to Camp #4

Days passed before further movement due to snow accumulation, high winds, and temperatures dropping near -5 degrees F. From 4-6 June, our team executed our planned double carry to Camp #4. We equipped our heavily loaded bags and began moving up to a deadly area known for its blue ice. Our team knew it was dangerous to sit static and risk frostbite as we encountered wind gusts from 35-40 mph, creating a wind chill of -34 to -43 degrees F. Delta Alders completed our first carry, caching selected gear around 14,200 feet before returning to our snowed-in camp and preparing for the next day’s move to Camp #4.

We cached skis at Camp #3 since the conditions on Squirrel Point and Windy Corner can be challenging without ski crampons. The risk of fall is high, and the previous day another climber fell to their death skiing down Squirrel Point. This news reinforced the importance of safety on such dangerous terrain. When we reached Camp #4 at 14,511 feet, we saw a shocking scene. Despite multiple avalanche slides and hidden crevasses on the slopes of the buttress, skiers accepted substantial risk in their recreation. National Park Service (NPS) representatives at camp expressed concern for these climbers as well as the high number of frostbite and altitude sickness cases this season thus far. Other camp members sunbathed in the open and chatted energetically with neighbors about their future endeavors. Our Delta Alders team accepted a quick invitation to drop gear and replenish water and snacks while basking in the warm sun. The trek between camps 3 and 4 during 4-6 June included moving 8.5 miles for 15 hours, ascending 6,023 feet.

Camp #4 to Camp #5

Once we arrived at Camp #4, bad weather once again persisted over several days. We thoroughly compared weather reports by consulting sources from the NPS, NWTC, and, most reliably, MSG Donnelly’s wife, Mara, who pulled multiple weather stations’ data on demand, giving comparisons for us to analyze. We had countless conversations about weather windows, equipment and ration load plans, and anticipated rates of movement while reaching higher altitudes. Deeper conversations carried on about altitude sickness, including recognition and treatment of life-threatening High Altitude Cerebral and Pulmonary Edema. As the Army had entrenched in our thinking for years, we prepared ourselves for worst-case scenario.

After days of preparation in anticipation of movement, weather reports displayed a three-day window for a summit. On 10 June, our Delta Alders team began to double carry to high camp at an altitude of 17,200 feet. This was the first time our team felt the lack of oxygen at high altitude. Digging the cache at high camp required multiple breaks and a continuous rotation of personnel. The use of pointed shovels as opposed to the typical flat snow shovel assisted in breaking through the icy snowpack.

As we reached the fixed lines during our return to Camp #4, we learned that an avalanche had buried two personnel. The NPS officer informed us that the rescue was underway, and we later learned only one climber survived. This news reminded us of the seriousness of our expedition. We prepared our campsite, packed out the minimal equipment necessary for a successful summit bid, and moved out to establish Camp #5 at 17,200 feet.

Camp #5 to Summit

The sketchy, 39- to 47-degree slope of the Autobahn traverse reduced movement to a crawl. Many teams traversed this famously dangerous feature on 12 June 2025.

Guided services and NPS personnel provided fixed-rope protection on this section of the mountain. Our team clipped into two sections on the traverse due to minimal crampon purchase with less-than-ideal axe placements. After hours on the Autobahn, we moved through historic landmarks such as Archdeacon’s Tower, the Football Field, and up Pig Hill to arrive at the summit ridge.

The weather this day was more than ideal for the summit bid, providing calm winds and sunny skies. However, the mountain still warranted caution as the usual avalanche activity clattered in the distance. As we slowly cut through the crusty snowpack, terrain feature after feature passed. Our minds filled with memories from the dozens of books we had read. This area of the mountain is filled with historic success, disaster, rescue, and heroism. Stories laid out in Colby Coomb’s Denali’s West Buttress: A Climber’s Guide revealed themselves in real time as we passed historic landmarks. Our confidence surged, and success seemed inevitable.

As we progressed along the switchbacks of Pig Hill, the climb became easier, and the summit felt within reach. Thousands of feet gave way to hundreds. A dream of ours that seemed out of reach 10 months ago was now an attainable goal in front of our faces. As the steps and long drawn breaths brought us closer, we climbed amongst Denali’s mountaineers to reach our high place on the summit of the tallest peak in North America — our prize was secure. We congratulated another team who we had become familiar with while we enjoyed the sweet taste of boiled water made from crusted snow thousands of feet below. We hoisted flags and captured numerous pictures and videos, feeling the sense of achievement.

After just over an hour on the summit, we re-focused on the next mission, a safe descent down to high camp. Over the next 22 hours, we traveled 14.1 miles, descending more than 10,500 feet to arrive at the lower base camp where we started our adventure.

The successes from our team’s experience echoed through formations in the 11th Airborne Division and served as a testament that hard work, accountability, committed discipline, and grit will lead to victory. There are many other key components that build a team like this one. The Delta Alders team traveled 47.4 miles over 96 hours, ascending 23,946 feet, and descending a total of 23,816 feet. We earned the respect of other climbers throughout our trek as we maneuvered the largest, heaviest sleds on the mountain, and stories echoed of the “Rangers” who summited in 16 days when faced with 10 days of poor conditions that later brought an early close to the entire mountain, an event that has not occurred in decades.

Climbing Denali was remarkable, and the support we received from the Arteries of Alaska Military Mountaineering (Steven Decker, Karl Slingerland, and Peter Smith) and climbing partners like SFC Jared Massey and SSG Jon Swope, made it even more extraordinary. The Army no longer uses the mountain to test equipment as it has specialized chambers nationwide to replicate extreme conditions and provide better equipment for Soldiers. Now, the U.S. Army’s relationship with the mountain is better suited for strengthening its greatest asset. This undertaking challenges military mountaineers to put absolute trust in their teammates, persist through adversity, meticulously plan for contingencies, apply technical skills in the field, make critical decisions under pressure, and ultimately endure hardship that is intrinsic to our profession and crucial to the future of military mountaineering.

Notes

1 Bradford Washburn and Lew Freedman, Bradford Washburn An Extraordinary Life (Portland: WestWinds Press, 2005).

2 SSG Matthew E. Windstead “Army Team begins Mount McKinley Climb,” Army News Service, 11 June 2012, https://www.army.mil/article/80175/Army_team_begins_Mount_McKinley_climb/.

3 Michael Wood and Colby Coombs, Alaska A Climbing Guide (The Mountaineers Books, 2001), 120.

4 Steve House, Scott Johnston, and Kilian Jornet, Training for the Uphill Athlete: A Manual for Mountain Runners and Ski Mountaineers (Ventura, CA: Patagonia, 2019).

5 Minus 148°: The Winter Ascent of Mt. McKinley by Art Davidson provides great additional information on the subject. Joe Wilcox’s White Winds: America’s Most Tragic Climb shares another firsthand experience of the largest disaster in Denali’s history.

6 Colby Coombs and Bradford Washburn, Denali’s West Buttress: A Climber’s Guide to Mt. McKinley’s Classic Route (Seattle: The Mountaineers Books, 1997).

7 “Why Did The 2025 Climbing Season End So Abruptly?” Mountain Trip Guides to the World’s Mountains, https://mountaintrip.com/trip-reports/why-did-the-2025-climbing-season-end-so-abruptly/.

CPT Edward M. Kwait currently serves as a training officer for the Army Mountain Warfare School in Jericho, VT. His previous assignments include serving as commander of Deadhorse Company, 1st Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Brigade Combat Team (IBCT), 11th Airborne Division, Fort Wainwright, AK; officer in charge of Training Branch, Northern Warfare Training Center, 11th Airborne Division, Fort Wainwright; and scout platoon leader, heavy weapons platoon leader, and operations officer in 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment, 1st IBCT, 10th Mountain Division, Fort Drum, NY. CPT Kwait is a graduate of the Infantry Basic Officer Leader Course, Maneuver Captain’s Career Course, Ranger Course, Reconnaissance and Surveillance Leaders Course, Air Assault Course, Basic Airborne Course, Mountain Warfare Course, Rappel Master Course, Basic Military Mountaineering Course, Advanced Military Mountaineering Course, and Cold Weather Leaders Course. He earned a bachelor’s degree in Kinesiology from Temple University and attended Alaska Avalanche School Level I and II. He also authored “The Case for Cold Regions and Mountain Operations,” which appeared in the Winter 2022-2023 issue of Infantry.

CPT Roy J. Schindler currently serves as commander of Ares Company, 1st Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment, 1st Brigade Combat Team, 11th Airborne Division, Fort Wainwright, AK. He previously serves as a scout platoon leader in Cherokee Company, 1st Battalion, 4th Infantry Regiment, Joint Multinational Readiness Center, Hohenfels, Germany. CPT Schindler is a graduate of the Basic Military Mountaineering Course, Mountain Planners Course, Ranger Course, and Reconnaissance and Surveillance Leaders Course. He earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from Norwich University.

MSG Corey J. Donnelly currently serves as the operations sergeant major for 5th Squadron, 1st Cavalry Regiment at Fort Wainwright, AK. His previous assignments include serving as a first sergeant in the 4th Infantry Division, Fort Carson, CO; a Ranger instructor in the 5th Ranger Training Battalion; and gunner-squad leader in the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), Fort Campbell, KY. MSG Donnelly is a graduate of the Master Leader Course, Maneuver Senior Leader Course, Sapper Leader Course, Advanced Military Mountaineering Course, Basic Military Mountaineering Course, Ranger Leader Course, Advanced Leader Course, Fast Rope Insertion and Extraction System (FRIES) and Special Patrol Insertion and Extraction System (SPIES) Master Course, Rappel Master Course, Basic Leader Course, and Air Assault Course. He earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration from American Public University.

This article appears as a bonus article for the Winter 2025-2026 issue of Infantry. Read more articles from the professional bulletin of the U.S. Army Infantry at https://www.benning.army.mil/Infantry/Magazine/ or https://www.lineofdeparture.army.mil/Journals/Infantry/.

As with all Infantry articles, the views herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of War or any element of it.

Social Sharing