During Warfighter Exercise (WfX) 25-01, the phrase “set conditions” was frequently used to describe prerequisites for initiating an action or transitioning between phases of the operation. While the importance of setting conditions was evident, there was often a divergent understanding of what specific conditions needed to be met and how to organize the planning cell’s efforts to enable them. Understanding which conditions should be time based and what actions should be driven by conditions is crucial to planning and executing large-scale combat operations (LSCO). This article explores how planning cells can organize efforts to anticipate requirements, preserve options, and exploit opportunities. A shared understanding of the specific conditions to support the commander’s intent for operations allows the planning cells to prioritize, coordinate, and adjust based on changes in a dynamic operational environment. Decisive military operations depend on fully informed staff integration and synchronization.

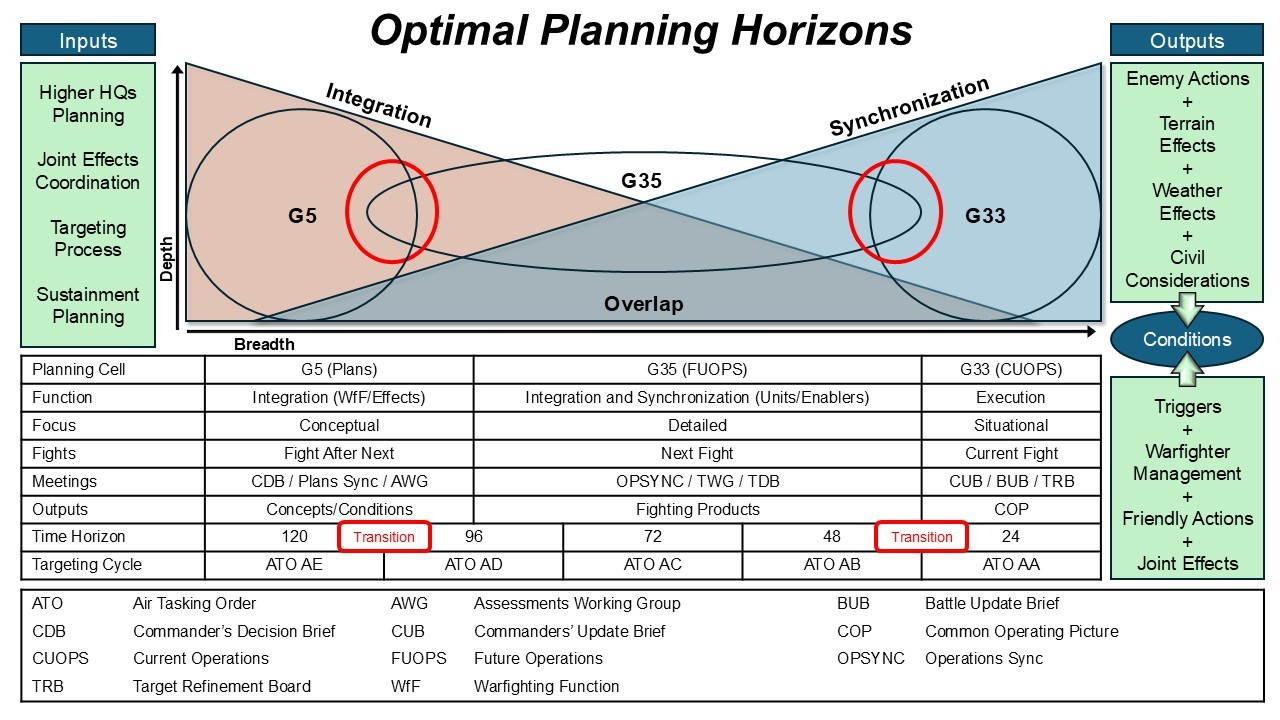

The effective execution of division operations relies on the seamless integration and synchronization of capabilities across different time horizons, with the G5 (Plans), G35 (future operations [FUOPS]), and G33 (current operations [CUOPS]) each playing critical roles in ensuring the division achieves operational success. The G5 focuses on long-term integration and condition-based planning. The G35 bridges the gap through mid-term, time-based synchronization, and the G33 ensures that plans are executed in real-time while adjusting to the changing operational environment. This article explores the distinct roles of these planning elements at the division level. In short, planning cells must pursue an optimal configuration that balances integration and synchronization.

Understanding Condition Setting in Division Operations

• Condition Setting: In military operations, condition setting refers to the deliberate actions taken to create favorable circumstances for the successful execution of future phases of an operation. According to Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations, commanders and their staffs assess the operational environment and adjust priorities, change task organization, and request capabilities to create exploitable advantages, extend operational reach, and preserve combat power (reference “How We Fight”).(1) This means that before initiating actions or advancing to the next phase of an operation, certain conditions — such as logistics readiness, control of key terrain, or the degradation of enemy capabilities — must be met to enable mission success.

• Definitions.

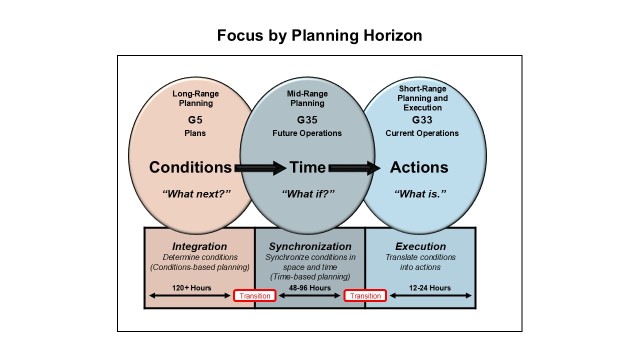

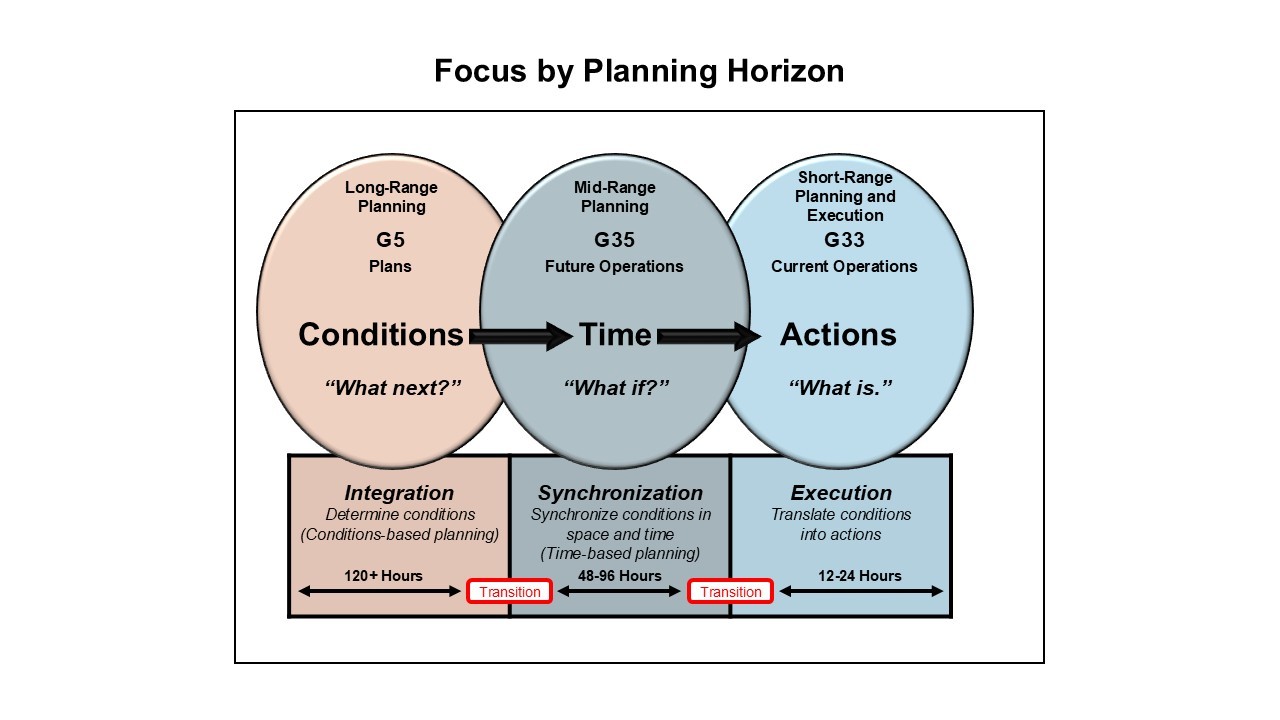

It is essential to establish a baseline understanding of integration and synchronization. FM 3-0 uses the concept of integration in multiple ways — the integration of warfighting function (WfF), capabilities, and the integration of units and enablers. From a practical perspective, integration brings everything to the fight coherently. Early integration is necessary due to the coordination required for outside joint and echelon-above-division assets and capabilities.

Synchronization is the arrangement of military actions in time, space, and purpose to produce maximum relative combat power in a decisive place and time.(2) It increases in importance as the plan approaches execution. However, due to the longer lead time for integration, synchronization cannot be achieved during early planning efforts. This suggests a difference in roles between Plans, FUOPS, and CUOPS.

Condition Setting Across Planning Horizons

Condition setting requires understanding the current operational environment and anticipating how subsequent battles will unfold. U.S. Army doctrine emphasizes that higher echelons, such as corps and divisions, synchronize joint capabilities to create opportunities while weighing the main effort appropriately. Staff sections must understand the specific conditions that must be met to ensure the balance of factors favors friendly forces.(3) This synchronization of efforts across domains enables higher echelons to degrade enemy capabilities at multiple levels, setting conditions that allow subordinate units to focus their efforts on decisive points. This is how the staff creates conditions for an “unfair fight.” This is anything but simple in practice, since a plan is defined by restraints, constraints, and resource limitations as much as by conditions that must be achieved.

The G5 Plans cell has sufficient standoff from the objective to visualize conditions within an environment where all things — or perhaps most things — can be brought to fruition. Contrast this with the G35 FUOPS cell, which operates at a horizon that more acutely feels the pressures of operational realities. This pressure results from reduced time to react in the mid-range planning horizon, which precludes those actions that require standoff (such as air support requests, echelon above brigade effects, or even logistics support) that have not been appropriately anticipated. Within the mid-range planning horizon, concepts must be carefully synchronized and coordinated so that actions materialize from intent. Mid-range planning is where concept statements become planned actions. The language for this transformation is time, and the product is windows of overlapping conditions within which opportunities are created that can be exploited.

It is within the short-range planning horizon and execution where actual constraints are realized and intended windows of opportunity are discovered to be either conceptual or reality. Here, weather and the adversary will challenge the completeness of the plan. Even uncontested, Murphy will do his best to identify where a plan lacks resilience and those areas overlooked during planning. The G33 must see beyond the plan’s mechanics and dynamically execute the operation based on conditions, limitations, and intent.

Figure 1 — Focus by Planning Horizon

Organizing Staff Efforts Around Condition Setting

What does it look like to organize staff efforts around condition setting? Here are five staff actions that directly relate to condition setting:

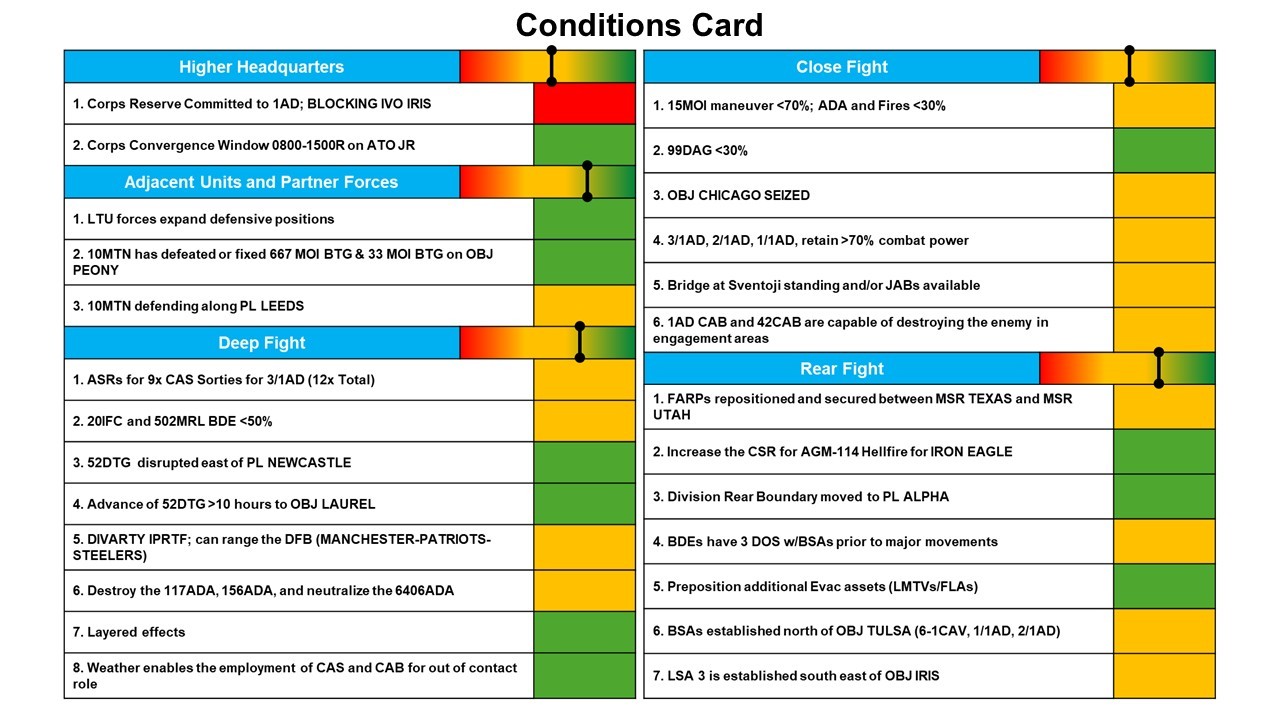

(1) Identify Critical Conditions for Each Phase of the Operation. At the outset of planning, the staff should clearly identify the specific conditions that must be met before transitioning to the next phase. These conditions might include securing critical terrain, achieving logistical readiness, or neutralizing key enemy capabilities. The running estimates created by each staff section must feed into this process, providing updated information on facts, assumptions, constraints, risks, and opportunities. This ongoing assessment enables commanders to adjust priorities and synchronize efforts to shape the battlefield effectively.(4) During WfX 25-01, the division staff understood the importance of reducing the air defense artillery (ADA) threat to enable attack aviation to defeat the enemy’s indirect fire capability as a condition for committing ground forces. The staff also realized that establishing forward arming and refueling points (FARPs) enabled sustained combat aviation brigade (CAB) operations. This example illustrates that one condition may lead to subsequent conditions that must be accounted for throughout planning and execution.

(2) Establish Decision Points Based on Conditions. The division staff must establish decision points that directly tie to the desired conditions to be set. This ensures commanders have clear criteria for when to move forward and what risk they are underwriting if the identified conditions are unmet. For example, if a key condition is the destruction of enemy air defenses to enable the CAB’s destruction of indirect fire assets, the decision to commit aviation units should be tied to the degradation of those enemy defenses. Understanding these conditions enables the division’s targeting effort to focus on the appropriate enemy capabilities with its surface-to-surface fires. Unleashing the full destructive power of the CAB on the enemy’s indirect fire capability sets conditions for our combined arms formations to maneuver on and destroy enemy formations or seize key terrain with reduced degradation of combat power.

(3) Synchronize Time-Based and Conditions-Based Actions. While conditions-based planning provides flexibility, time-based planning ensures that operations progress on schedule. Doctrine emphasizes that higher echelons retain control of scarce resources and use them at discreet times and places.(5) The staff must carefully synchronize both approaches by identifying when time dictates action. For example, certain windows of opportunity — such as favorable weather or fleeting enemy vulnerabilities — might force commanders to act before all conditions are fully met. In these cases, time becomes the driving factor, and the staff must adjust their plans to take advantage of the opportunity, even if specific conditions are incomplete.

(4) Use Deep Operations to Shape Future Conditions. Deep operations are critical for setting conditions for success in future close operations. According to FM 3-0, deep operations influence the timing, location, and enemy forces involved in future battles.(6) The staff must organize their efforts to ensure that deep operations — such as targeting enemy long-range fires or disrupting command and control nodes — are aligned with the overall conditions to be deliberately set. By weakening the enemy’s ability to defend or maneuver, deep operations pave the way for successful close combat, enabling the force to engage more favorably.

(5) Monitor Progress and Adjust as Necessary. Throughout the execution of operations, commanders and staff must continually assess whether the desired conditions are being met. FM 5-0, Plans and Orders Production, emphasizes the importance of monitoring the operational environment and adjusting the operational approach as needed.(7) If conditions are not being set as planned or the operational environment changes, the staff must be prepared to adjust timelines, reallocate resources, or develop new courses of action (COAs). This iterative process ensures that operations remain flexible and responsive to the evolving battlefield.

Figure 2 — Example Conditions Card

Aligning Planning Efforts — Finding an Optimal Configuration

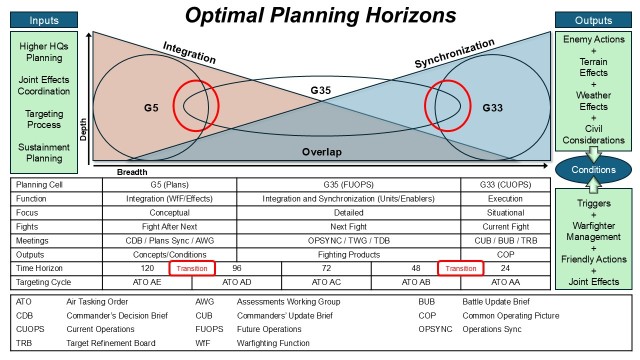

A division staff must follow a structured approach that integrates both time and conditions-based planning to organize efforts around condition setting effectively. This involves identifying what conditions must be met and a shared understanding of when time dictates actions regardless of conditions. Organizing the staff’s efforts around condition setting starts with defining the focus for integrating cells during the three planning horizons. The optimal planning configuration will balance integration and synchronization across planning horizons with the three integrating cells.

Figure 3 — Optimal Planning Horizons

Conditions and transitions are inherently linked.(8) Transitions occur in many forms during LSCO: between types of operations, from phase to phase, between mission command nodes, or from the base plan to a branch or sequel. Managing transitions is critical to maintain tempo and enable decision dominance.

The staff’s framing of the running estimate reflects the focus of each planning horizon. A look at each running estimate across integrating cells illustrates the separate-but-complementary focus of each planning horizon. The example below shows how these estimates inform condition setting across horizons.

The optimal planning horizon is one where each planning cell can apply maximal time, effort, and personnel to their function, focus, and fight in a way that creates effective meetings with quality outputs. Due to the depth and breadth of planning possibilities, there is an inherent balance between specialization and overlap. The plan’s transition between cells is the critical event to manage the balance. When any of these areas shifts out of balance and the transitions need to be timelier or better executed, the result is one of the suboptimal planning horizons.

The G5 initiates planning in the domain of 120-72 hours. This planning cell is best positioned to integrate capabilities and enablers based on the longer lead time planning required for joint effects, targeting, and sustainment. The G5 develops the initial set of favorable conditions necessary for mission success.

The G35 conducts planning between 72-24 hours and is at the overlap of integration and synchronization as expressed through the fighting products –– the synchronization matrix, the execution checklist, and the conditions card. They translate theoretical conditions into planned, time-based actions given a forecast of forces available and the operating environment. As a result, the FUOPS cell experiences a bi-directional pull toward plans and current operations. This reduces the ability of the FUOPS cell to generate depth in integration or synchronization. In other words, the FUOPS cell’s most important contribution is the breadth of planning efforts that link the end state to the current state.

G33 then translates the time-based plan into actions given the operational realities. They accomplish this by using situational understanding to develop a common operating picture and create a shared understanding between subordinate units and the staff.

The Plans-FUOPS and FUOPS-CUOPS transitions must be detailed battle rhythm events that manage the knowledge transfer between cells. Informed by a seven-minute drill, each transition must have a measurable outcome expressed through transition products. The most important attributes of the plan’s transition are consistency in format, detail, and the level of coordination presented in a tangible format. A successful transition enables the continued development of the plan as it approaches execution.

The running estimate is another product the planning cells can use to maintain balance through the planning horizons. Each planning cell must maintain a running estimate that clearly and concisely articulates its function, focus, and fight. Each running estimate should be a shared, collaborative, and easily accessible document that maximizes knowledge management and minimizes the obstacles to parallel planning. This is especially important when command posts and planning cells are disaggregated or dispersed Figure 4 highlights how each running estimate should have a different but complementary focus.

Figure 4 — Framing the Running Estimates

Planning Pitfalls. FM 5-0 examines seven common planning pitfalls.(9) While every planner should avoid these, it is beneficial to recognize that certain cells are more susceptible to some pitfalls than others.

Planning cells most susceptible to planning pitfalls:

• Lacking commander involvement – G35 FUOPS

• Failing of the commander to make timely decisions – G5 Plans

• Attempting to forecast and dictate events too far into the future – G5 Plans

• Trying to plan in too much detail – G5 Plans

• Using the plan as a script for execution – G33 CUOPS

• Institutionalizing rigid planning methods – All

• Lacking a sufficient level of planning detail – G5 and G35

Recognizing the pitfalls that each cell is most likely to encounter allows for evaluating suboptimal planning horizon configurations that are likely to occur throughout the planning effort.

Suboptimal Configurations

Figure 5 — Suboptimal Planning Horizons

A suboptimal planning configuration is any planning horizon array that needs to be balanced. The illustrations shown in Figure 5 highlight examples when one or more planning cells operate outside their intended function, focus, or fight. Note that each shape represents the bandwidth of the planning cells as constrained by work capacity, time available, and planning priorities. Because planning possibilities always outweigh available planning bandwidth, the staff must have a direction aligned with planning priorities. The ability to see yourself and recognize suboptimal configurations enables the division staff to realign planning priorities to return to the optimal configuration.

• “Collapsed Horizons.” Collapsed horizons represent a suboptimal planning configuration where the focus of each planning horizon breaks down, resulting in a lack of cohesion and a reactive operational stance. This is the most common suboptimal planning horizon. In this scenario, the planning horizons merge unintentionally, often due to a high operational tempo, which may prevent proper integration of joint and interagency resources or timely condition setting. Consequently, the division’s targeting efforts become more reactive than proactive, responding to immediate threats without the flexibility to exploit long-term opportunities or shape the battlefield ahead of maneuver forces. The resulting fixation on the current fight limits the ability to coordinate for high-level, joint resources and effects that typically require advance planning and disrupt connections with higher headquarters and adjacent units. When horizons collapse, the staff becomes constrained and unable to allocate resources effectively or maintain operational depth, leading to delayed decisions and an increased risk of facing dilemmas instead of imposing them on the enemy.

• “Planning Deadspace.” Planning deadspace occurs when the Plans cell attempts to conceptualize too far out and creates conditions that do not link to the FUOPS cell’s planning fidelity — typically observed by gaps in the synchronization matrix (SYNCMAT) or one that presents an unfeasible plan. This creates a gap between the end state and current actions. Some indicators of this suboptimal planning horizon include planning efforts that are never executed, underdeveloped branch plans, and the absence of decision points that provide sufficient standoff to adjust the plan. Another clear indicator is that the Plans-to-FUOPS transition attempts to transition a plan that does not logically link with current time-based conditions. When there is planning deadspace, the execution lacks an understanding of the broader context of the operation. Therefore, the division forgoes opportunities and does not anticipate requirements based on the gap between Plans and FUOPS.

• “Head in the Clouds.” Planning efforts are not connected with the conditions for execution. This typically occurs when the plan does not evolve with the conditions in the operating environment. Some indicators of this suboptimal planning horizon are when fighting products and decision support tools are incomplete or irrelevant and decisions are made in execution that forgo future opportunities. Another contributing factor that leads to this suboptimal configuration is when a staff rigidly adheres to the optimal planning configuration rather than recognizing when it is necessary to maximize effort on specific planning efforts.

• “Planning Silos.” This is the most recognizable suboptimal planning configuration. It can occur in degraded communication windows, distributed locations, poor command post layouts, different planning cells obtaining information from various sources, or one or more planning cells focusing on disparate planning priorities. Planning silos leads to duplication of effort, limited depth in the final plan, a lack of shared understanding, and an inability to see ourselves. Some indicators of this suboptimal planning horizon include redundant planning efforts, clumsy or non-existent transitions, and a lack of communication between planning cells.

• “Disconnected from Reality.” This is the least likely but most dangerous suboptimal configuration. The CUOPS cell has the least flexibility to deviate from its function. The CUOPS cell has an outsized role in keeping the division connected to operational realities by providing broad situational awareness. Some indicators of this suboptimal planning configuration include duplication of planning effort, limited depth in execution decisions, and a lack of shared understanding between headquarters, staff sections, and subordinate units. The easiest way to become disconnected from reality is to execute the plan like a schedule, resulting in “fighting the plan and not the enemy.”

Recovering — Getting Back to Optimal

Combat operations will naturally ebb and flow. Horizons will begin to collapse as operational tempo increases. It is critical for staff sections to quickly recognize the pull towards suboptimal configurations and deliberately fight to get back to the optimal configuration. The staff should use periods of decreased tempo to reestablish planning horizons. A deliberate economy of force in planning will assist with recovering from suboptimal configurations. For example, the Plans cell should solicit additional planning guidance and/or seek additional decisions from the commander to reestablish horizons. The FUOPS cell may need to transition plans early to increase the depth of planning at a greater distance from current operations. The CUOPS cell can increase the use of the rapid decision-making and synchronization process (RDSP) and deliver radio orders to create planning space for the FUOPS and Plans cells. When a staff determines it is in any suboptimal planning horizon, recovery requires the planning cells to regain balance by reconnecting actions with time-based conditions and concepts in a bottom-up sequence. As the plan transitions between horizons, add time to concepts and situational understanding to time-based products as plans transition between horizons.

Key Insights

The following 10 takeaways can immediately be implemented to balance integration and synchronization in planning:

(1) Do not synchronize too early; do not integrate too late.

(2) Recognize when the staff is in a suboptimal configuration and fight to get back to optimal.

(3) Integrating cells must prioritize their function, focus, and fight (do what they do best).

(4) Integration means different things in each horizon; integrating cells must integrate.

(5) Each horizon contributes to the running estimate in a unique way.

(6) Integrate and synchronize simultaneously but avoid chasing a perfect plan. A 70-percent complete plan now may remain viable where a 100-percent plan would be too late. Anticipate that refinements at the next horizon will complete the plan. Therefore, focus on transitions between horizons and allow time for subordinate refinements.

(7) Design the staff around deliberate condition setting.

(8) Add time to concepts and situational understanding to time-based products as plans transition between horizons.

(9) It is important to understand conditions even if they are not the ones you want.

(10) Maintaining planning horizons enables the commander to anticipate requirements, exploit opportunities, and preserve options. This is crucial to achieving decision dominance and imposing dilemmas on the enemy. Conversely, collapsed planning horizons eliminate options and increase the probability of facing dilemmas.

Conclusion

Balancing integration and synchronization across the planning horizons is critical to achieving success in LSCO. 1st Armored Division staff insights from Warfighter 25-01 highlight the importance of setting conditions at each stage of the operation, ensuring that each planning cell focuses on its unique role while maintaining seamless coordination with other staff sections, especially during transitions. Successful operations depend on recognizing when planning horizons become suboptimal and actively working to restore balance through careful management of both time-based and conditions-based actions. The optimal configuration for planning horizons requires designing staff efforts around condition setting with a clear understanding of when to prioritize integration and when to focus on synchronization. This balance of focus ensures flexibility, mitigates the effects of suboptimal planning configurations, and enables decision dominance. Ultimately, it results in planning efforts that empower commanders to impose complex dilemmas on the enemy and achieve operational success by anticipating requirements, exploiting opportunities, and preserving options.

Notes

1 Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations, October 2022, 1-53, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN36290-FM_3-0-000-WEB-2.pdf.

2 Ibid., 3-18.

3 Ibid., 2-80.

4 Ibid., 1-53.

5 Ibid., 2-80.

6 Ibid.

7 FM 5-0, Plans and Orders Production, November 2024, 4-95, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN42404-FM_5-0-000-WEB-1.pdf.

8 FM 3-90, Tactics, May 2023, 8-134.

9 FM 5-0, 1-113.

MAJ Samuel Fujinaka is currently a G35 plans officer for the 1st Armored Division at Fort Bliss, TX. He has a Bachelor of Science from the United States Military Academy at West Point, a Master of Business Administration from Georgetown University and a Master of Operational Studies (MOS) from the Command and General Staff Officer Course at Fort Leavenworth, KS. His previous assignments include commanding a battery in the 1st Infantry Division at Fort Riley, KS, and a headquarters and headquarters battery for 1st Infantry Division Artillery.

MAJ Audley Campbell is currently a G5 planner for the 1st Armored Division at Fort Bliss. He has a Bachelor of Science from New Jersey City University, a Master of Public Administration from Rutgers University, an MOS from the Command and General Staff Officer Course, and a Master of Arts in Military Operations from the School of Advanced Military Science (SAMS) at Fort Leavenworth. His previous assignments include troop command in the 1st Infantry Division at Fort Riley and serving as an Infantry Captains Career Manager in Human Resources Command (HRC) at Fort Knox, KY.

This article appears in the Winter 2025-2026 issue of Infantry. Read more articles from the professional bulletin of the U.S. Army Infantry at https://www.benning.army.mil/Infantry/Magazine/ or https://www.lineofdeparture.army.mil/Journals/Infantry/.

As with all Infantry articles, the views herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of War or any element of it.

Social Sharing