The method used by American football teams to call offensive plays changed drastically in the early 2000s. Deemphasizing the huddle, numerous teams experimented with calling plays from the line of scrimmage. This technique, perhaps best exemplified by Peyton Manning and the Indianapolis Colts, allowed the quarterback to deliberately survey the defense and exploit weaknesses by getting the team in the optimal play. This change allowed the Colts to play at an increased tempo compared to offenses that huddled and disadvantaged defenses by not allowing time to make substitutions. Expanding on the no-huddle offense, Coach Chip Kelly and the Oregon Ducks further innovated by calling plays at the line of scrimmage via posterboard signals from the sideline. Rather than deliberately surveying the defense and selecting the perfect play, Kelly rapidly disseminated information to the offense and increased Oregon’s offensive tempo, even compared to teams that employed the Colts’ technique. Increased tempo exploited weaknesses in the opposing defense as their players could not communicate and ensure common understanding before Oregon started the next play. Inevitably, Oregon took advantage of defensive mistakes, oftentimes scoring long touchdowns at the expense of a defensive player who was out of position.

Emulating the Oregon Ducks, U.S. Army maneuver battalions can rehearse battle drills and pre-scripted “plays” during home station collective training to increase readiness for the rapid tempo required to fight and win in large-scale combat operations (LSCO). Recently, the U.S. Army has reorganized with the division replacing brigade combat teams as the unit of action.1 As divisions focus on tactical level operations, planning horizons at lower echelons contract.2 Gone are the days of counterinsurgency operations whereby battalions, companies, and platoons have days or weeks to plan a raid, humanitarian assistance drops, or other small unit operations.

U.S. Army organizations at the brigade level and below understand this dynamic and have made significant adjustments to increase tempo. Observer controller/trainers (OC/Ts) at the U.S. Army’s combat training centers (CTCs)emphasize the importance of issuing timely orders and building flexibility in tactical plans.3 A best practice highlighted by the Army’s Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC) OC/Ts is brigades adhering to the “1/3-2/3 rule” during a three-day battle period.4 This means that a brigade uses only 24 hours to plan and issue an order, giving subordinate echelons the ability to plan and rehearse over 48 hours at echelon before execution. This abbreviated planning timeline is akin to the early Indianapolis Colts no-huddle offense and its ability to utilize available time to survey the defense and call the optimal play at the line of scrimmage.

In this scenario, maneuver battalions are given the time necessary to run their own military decision-making process (MDMP) and implement the optimal plan for the current conditions in the operational environment. Undoubtedly, there are numerous situations in LSCO where this technique is appropriate and enables success. However, even the abbreviated timeline highlighted above does not align with the tempo at which divisions execute operational transitions and issue orders to brigades during warfighter exercises (WFXs) in LSCO scenarios. Therefore, in addition to proficiency in MDMP, maneuver battalions must be trained to execute battle drills when tempo dictates minimal time for preparation and no time to plan.

During WFXs, the changing nature of the operational environment (OE) often leads a division to issue fragmentary orders that drastically change a subordinate brigade’s task and purpose less than twelve hours before the execution of an operation.5 Given the simulated environment of a WFX, well-rested and all-knowing brigade staffs can quickly implement changes and ensure common understanding with “pucksters” serving as their subordinate battalion commanders as they are co-located within the same room. These “pucksters” are then immediately ready to execute as they have sole responsibility for maneuvering entire battalions and do not need to ensure common understanding at the company and platoon level.

Undoubtedly, this order dissemination process would be very different on a modern battlefield whereby a brigade had to contend with disparately located subordinate units, contested communications, sleep deprivation, enemy actions, and a litany of other issues. Even the best brigade would be hard-pressed to adhere to the 1/3-2/3 rule and issue a plan in under four hours, a full twenty hours quicker than the JRTC best practice highlighted above. Still, battalions, companies, and platoons would each need to undergo their own planning and orders dissemination process before common understanding of an optimal plan could be achieved. Instead, it is necessary that maneuver battalions develop a “playbook” and train on battalion-level battle drills or “plays” before experiencing combat. Like the Oregon Ducks posterboard play calls, a maneuver battalion playbook with one-word radio calls for numerous operations would allow battalions to rapidly disseminate a feasible plan and ensure common understanding down to the platoon level. This playbook postures the battalion for success when tempo dictates that near-immediate action is necessary. As stated by GEN George S. Patton there are occasions in LSCO in which, “A good plan violently executed now is better than a perfect plan executed at some indefinite time in the future.”

How Can Battalions Do This?

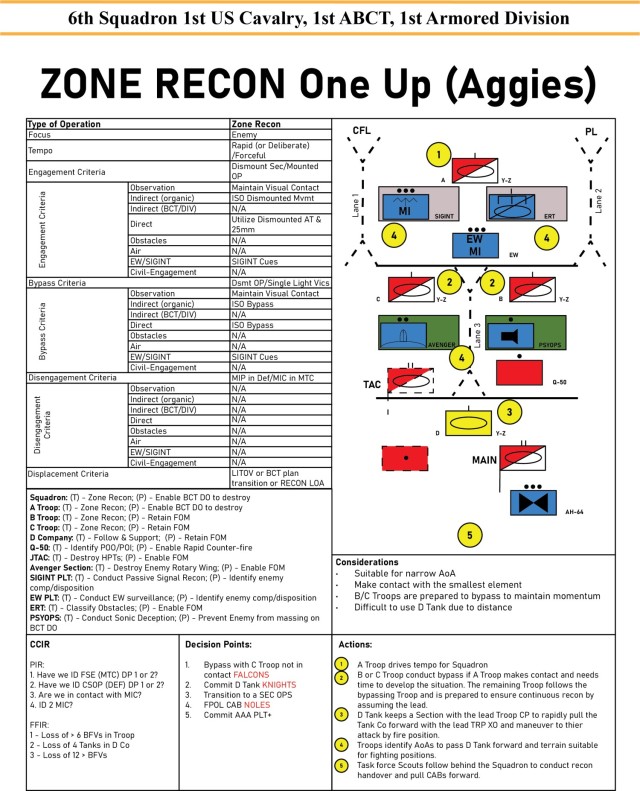

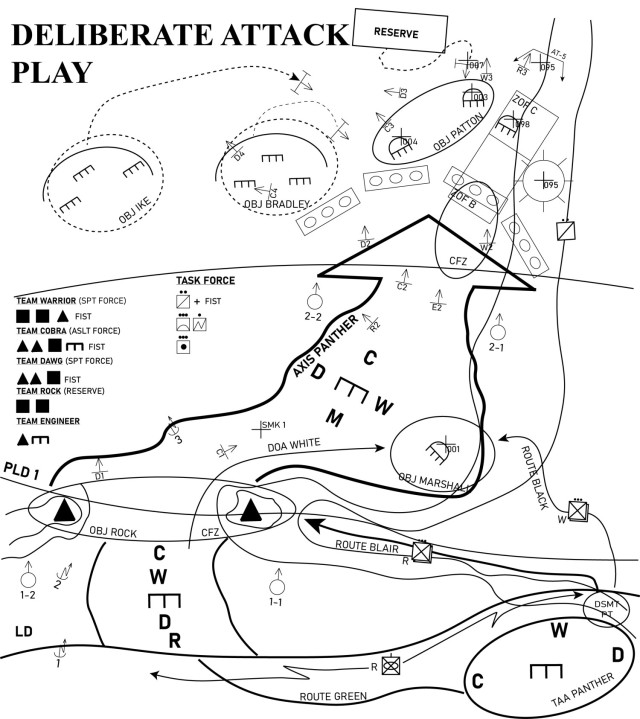

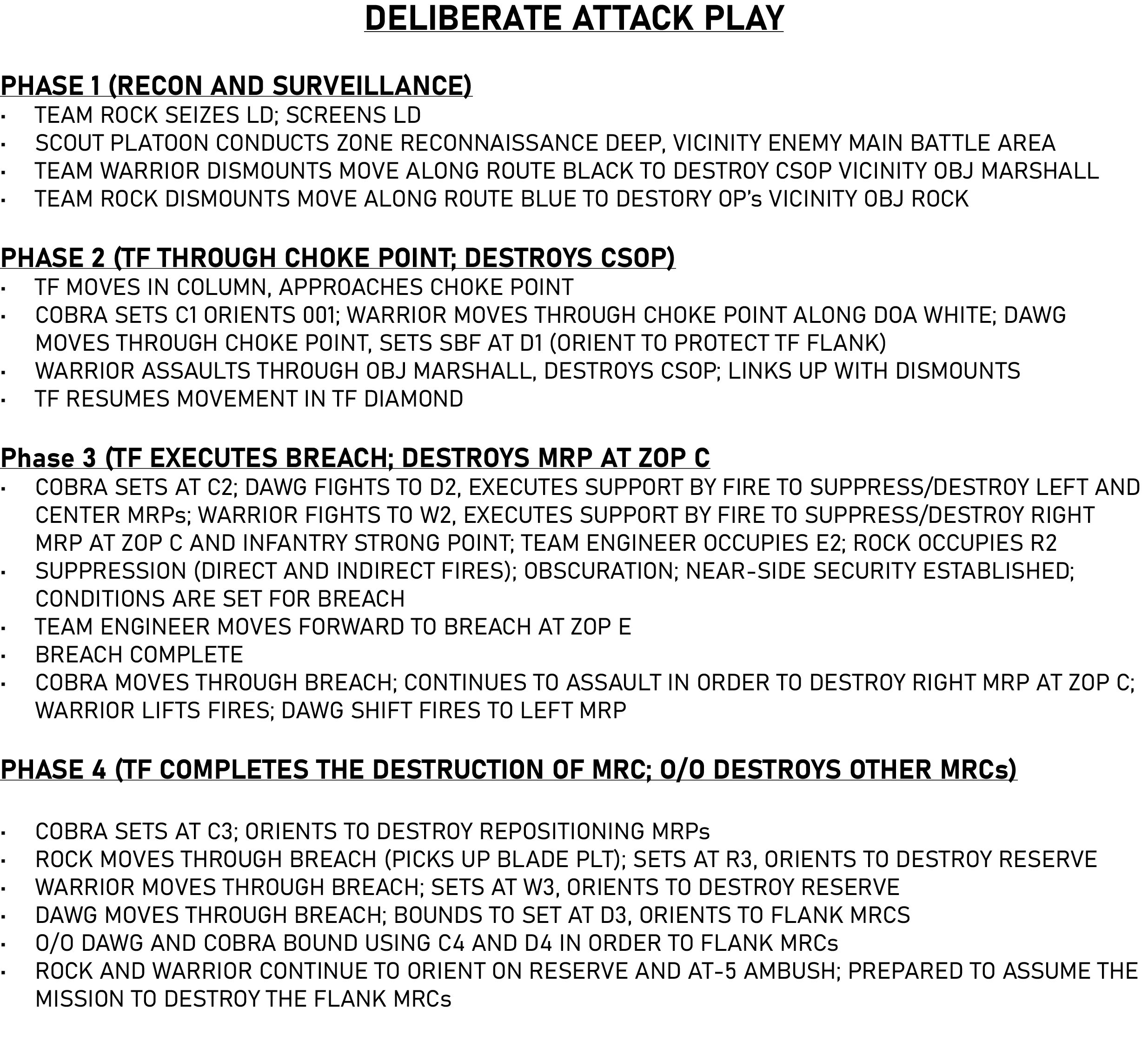

Maneuver battalions must make changes to their home station training plans if they hope to successfully implement battle drills during CTC rotations or war. The first step is to utilize working groups to develop a battalion playbook to illustrate how the battalion organizes and executes its typical mission sets. At a minimum a maneuver battalion playbook should include a “card” or “play” on hasty attack with a flanking maneuver left, hasty attack with a flanking maneuver right, frontal attack, movement to contact, hasty breach, defense of a linear obstacle, and a mobile defense. A cavalry squadron playbook should include “plays” for screen, guard, zone reconnaissance, the reinforcement of a cavalry troop by the tank company, passage of lines, and reconnaissance handover between troops. These working groups must include representatives of all warfighting functions so that each “play” outlines a coherent scheme of intelligence collection, fires, protection, and sustainment in addition to the scheme of maneuver. Once developed, battalion leader professional development (LPDs) can be held to review the product and ensure common understanding of each play down to the platoon level. Leaders must understand that this is not the right way in which the battalion will execute these missions in any scenario, only a template used to ensure immediate common understanding when MDMP is not feasible. Finally, staffs must understand that, in execution, they are still responsible for rapidly distributing updated graphic control measures, fire support control measures, identifying triggers, and producing any other fighting products the commander deems necessary to adapt the “play” to the operational environment in which it will be executed.

It is not enough for battalions to produce and distribute the playbook, they must also put it into practice during training. Time must be dedicated on the battalion training calendar for multiple companies to rehearse “plays” collectively under the command and control of a battalion command post. Tactical exercises without troops (TEWTs), the close combat tactical trainer (CCTT), and reduced force exercises are outstanding techniques to conduct this training within realistic resourcing constraints. Multiple iterations of situational training exercises (STXs) comprising force-on-force scenarios are invaluable in improving a battalion’s ability to succeed on short notice as they allow leaders to make mistakes, learn, and retrain. Ensuring that these events receive the same focus and prioritization as live-fire exercises greatly increases a battalion’s capacity for agility and it’s ability to react quickly within the bounds of the commander’s intent.

What Can Division and Brigade Headquarters do to Enable Success at the Battalion Level?

Battalions cannot develop playbooks in a vacuum as they must be nested within the context of how their brigade and division intends to fight. For example, an armored or armored strike division that is unlikely to employ more than one infantry battalion in an air assault does not need multiple maneuver battalions prioritizing air assault operations in collective training. Conversely, an armored strike division cannot assume an adequate number of subordinate battalions will master the combined arms breach absent guidance and oversight. Divisions must clearly prioritize and articulate the tasks that subordinate brigades and battalions must be prepared to execute. Brigades must do the same for battalions and companies. This articulation can be done through “how we fight” products and LPDs but must be reinforced through actionable, relevant annual training guidance. Training guidance cannot simply regurgitate all regulatory annual training requirements but must prioritize areas in which subordinate organizations must excel, areas where they must perform to standard, and- most importantly- areas where units can assume risk and remain untrained. Divisions and brigades that simply list all regulatory requirements absent prioritization are pushing risk decisions down to lower levels. Some portion of training will still be omitted or conducted at a substandard level, but those prioritization decisions will be made by company grade officers and junior noncommissioned officers rather than senior leaders.

Furthermore, divisions and their subordinate brigades must ensure their unit culture inculcates effective and adaptive LSCO-oriented training. In the words of former United States Army Europe and Africa (USAREUR) commander LTG (R) Arthur Collins Jr. – himself no stranger to leading Soldiers during transition periods between wars – “skillful senior commanders can bring their armies into battle under favorable conditions, but it is the small unit leaders who win the battle.6 All Army organizations perform a host of necessary activities that may degrade from training if not managed appropriately. These activities include- but are not limited to- personnel actions, inspections, promotion boards, supply activities, planned and unplanned maintenance, unit social functions, and community outreach. These requirements exist to ensure a unit remains administratively prepared to perform its mission, therefore senior leaders must consistently message the importance of warfighting. If unit commanders fail to place the appropriate emphasis on high-quality, battle-focused training, then even the most well-developed playbook has little value.

While division and brigade leaders work to establish appropriate training environments, battalion-level leaders must do their part and meet their higher headquarters in the middle. These lower echelon commanders must manage administrative requirements without missing the “forest for the trees” by focusing on what is urgent rather than what is essential. LTG Collins observed that even as far back as the 1970s, many battalion commanders and their staff officers complained about a lack of training time and the crushing weight of excessive training requirements issued by higher headquarters.7 Yet, in his experience, such units simply suffered from a failure to prioritize resources (especially time) or emphasize appropriate training – these commanders let their training manage them rather than managing their training.8 With effective playbooks in hand, battalion and company commanders must reinvigorate emphasis on combined arms training through the execution of the STX lanes, TEWT iterations, and other methods described above.

What Other Doctrine, Organization, Training, Materiel, Leadership and Education, Personnel, and Facilities (DOTMLPF) Changes are Required?

Above the division level, the larger U.S. Army can help facilitate adaptation through additional changes across the DOTML-PF spectrum. From a personnel standpoint, much has already been written about the fiscal and family stability benefits of adopting a U.S. Army divisional system that required less permanent change of station.9 An additional benefit of increased Soldier stability is that it enables battalions to capture lessons learned from collective training and implement standard operating procedures (SOPs) that are understood at echelon. Currently, battalions peak in combat readiness every two years after a CTC rotation; however, they are rarely able to build on that level of readiness and continue to progress over the following two-year cycle. Instead, massive leader and Soldier turnover means that the battalion must rebuild systems and processes from the ground up. The need to continue to train, qualify, and recertify new crews, sections, and platoons leaves little time to train above the company echelon until the next CTC rotation, thereby restarting the cycle again. Reducing Soldier moves through a divisional system would mitigate this cycle through increased unit familiarity with SOPs, less turnover and training required for additional duties, and more efficient leader onboarding due to post and unit familiarity.

The Combined Arms Doctrine Directorate (CADD) can also assist battalions in revamping collective training plans in its next update to FM 7-0, Training. FM 7-0 accurately defines battle drills as, “a collective action where Soldiers and leaders rapidly process information, make decisions, and execute without a deliberate decision-making process.” However, its description of lane training indirectly reinforces the notion that battle drills are only executed at the company level and below. Lane training is defined as, “A company and below training technique designed to practice, observe, and evaluate individual tasks, collective tasks, or battle drills. It allows the unit to focus on the critical tasks, allows for consistent and uniform assessments, and maximizes the use of available time.” As lane training is the prescribed medium for training battle drills, and, by definition, lane training is not executed at the battalion and brigade level, one can presume that battalions and brigades do not execute battle drills and instead conduct a deliberate decision-making process at the outset of every operation. Furthermore, while FM 7-0 includes several helpful vignettes that describe how units can plan and execute training, nearly every vignette is codified at the platoon or company level. The inclusion of vignettes and techniques to effectively train multiple companies or whole battalions would be a beneficial addition. An example might be lane training where two companies conduct a movement to contact against the battalion’s third company, scout platoon, and mortar platoon. The first element can be controlled by the battalion’s main command post while the second element is controlled by the battalion tactical command post or mobile command group. With reduced time committed to planning, the battalion could conduct multiple iterations of lane training in a given day, before flipping sides and repeating the event the next day. Iterative training events like this allow leaders and units to experiment, learn from mistakes, adjust SOPs, and build the trust necessary to execute mission command. Arguably, training of this nature would be more beneficial in combat than the rote progression through smaller echelon live-fire training that most units currently prioritize.

Conclusion

Today’s leaders must evolve training methodologies to prepare to win the first battle of the next war. As the operational environment becomes increasingly dynamic, maneuver battalions must be able to adapt and respond with speed and agility. The development of battle drills, playbooks, and rigorous home station training programs can provide a critical foundation for success in this context.

By leveraging these approaches, battalions can foster a culture of initiative, decentralization, and mission command, where units are capable of rapid action to dictate tempo in a changing environment. This, in turn, can enable divisions to seize and maintain the initiative, exploit weaknesses in enemy defenses, and ultimately achieve victory.

As the U.S. Army continues to transform, leaders and trainers must prioritize innovation, creativity, and experimentation in their approach to training and readiness. By doing so, the Army can ensure that its maneuver battalions are equipped with the skills, knowledge, and adaptability necessary to succeed in the most demanding operational environments.

Major Chris Garlick is a Command-and-Control Observer/Coach/Trainer in Operations Group Charlie, Mission Command Training Program at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. His previous assignments include Cavalry Squadron Executive Officer, Cavalry Squadron Operations Officer, Security Force Advisor Maneuver Team Leader, and Armor Company Commander.

Lieutenant Colonel Dave Devine is a Brigade Operations Observer Coach/Trainer on the Bronco Team at the National Training Center, Fort Irwin, California. His previous assignments include Brigade Executive Officer, Cavalry Squadron Executive Officer and Operations Officer, Security Force Advisor Troop Commander, and Cavalry Troop Commander.

Notes

1 Pomerleau, M. February 13, 2023. “Division Headquarters Will Now Accompany Brigades to Combat Training Center Rotations.” Defense Scoop. Accessed August 18, 2025. https://defensescoop.com/2023/02/13/division-headquarters-will-now-accompany-brigades-to-combat-training-center-rotations/

2 Reed, William, and Jose DeLeon. 2024. “The Agile U.S. Army Division in a Multidomain Environment.” Military Review, 39.

3 Lee, James, and Anthony Formica. 2024. “Setting the Conditions for Brigades and Battalions to Succeed in LSCO through Staff Overmatch.” The Crucible- The JRTC Experience Podcast, July 17, 2024. https://www.jrtc.army.mil/podcast/.

4 Ibid.

5 Center for Army Lessons Learned. 2024. FY23 Mission Command Training in Large Scale Combat Operations Key Observations. Center for Army Lessons Learned, 13.

6 Collins, A. (1978). Common sense training: A working philosophy for leaders. Presidio Press.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Hurst, J. 2023. “Move Soldiers Less: A Divisional System in the U.S. Army.” War on the Rocks, August 30, 2023. Accessed August 18, 2025. https://warontherocks.com/2023/08/move-soldiers-less-a-divisional-system-in-the-u-s-army/

Social Sharing