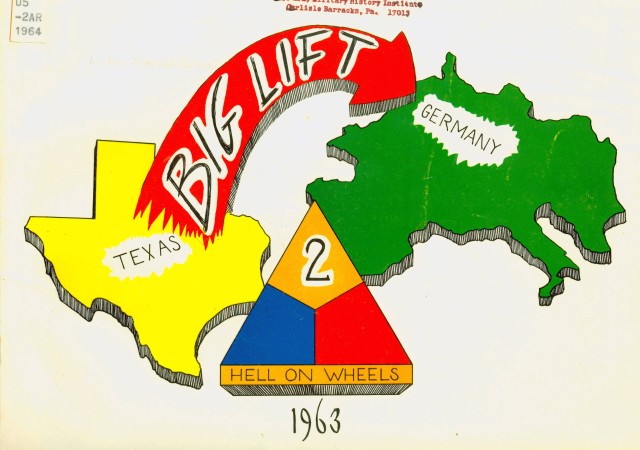

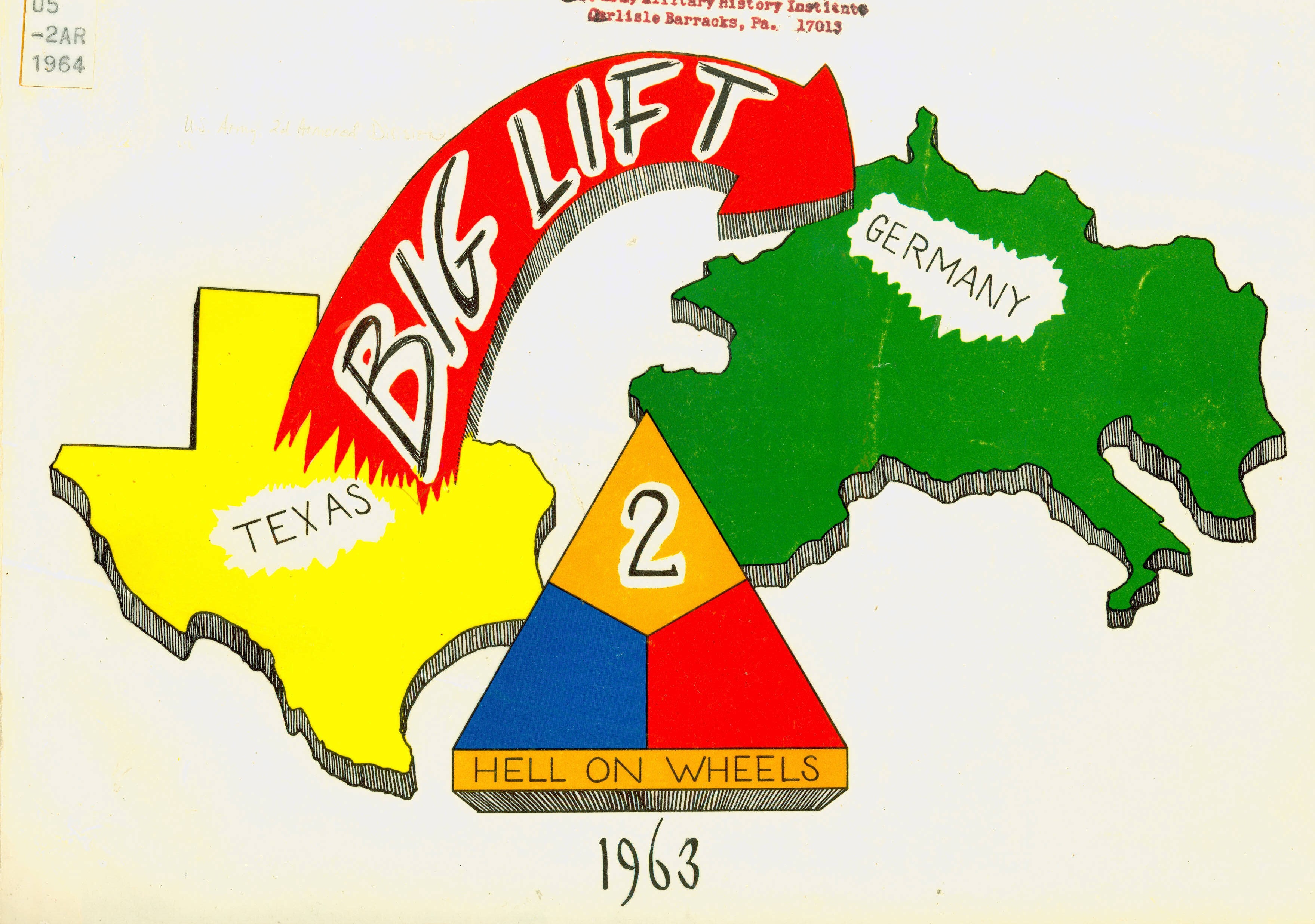

In the early morning of October 22, 1963, soldiers of the 2nd Armored Division at Fort Hood, Texas, lumbered up with their gear and individual weapons to an assembly of large cargo aircraft from the Military Air Transportation Service. Their destination was the front-line of the Cold War's Central Europe.

Over the next 64 hours, the division, two artillery battalions, and assorted transportation units from around the country made the day-long flight across the Atlantic. An air strike force went as well. Altogether, the planes made over 200 flights, ferrying some 15,000 personnel and nearly 500 tons of equipment, one quarter of which belonged to the Army. It was the largest movement of troops by air to that date.

The deployment had been ordered by the U.S. government in consultation with its NATO allies to stem a likely attack by Warsaw Pact forces into West Germany. The scenario, however, was entirely notional. Instead of being met by hundreds of enemy tanks, the incoming troops were greeted by a 250 pound cake in the shape of a tank. The operation was, in fact, a preplanned exercise, aptly named BIG LIFT. Its actual purpose, as Defense Secretary Robert McNamara announced in a September 23 press conference, was to "provide a dramatic illustration of the United States' capability for rapid reinforcement of NATO force."

Upon arriving in Europe, the soldiers made their way to strategically located depots where they collected a wide array of heavy equipment. The Army had stored the items -- enough for two divisions and ten combat support elements -- following the 1961 Berlin Crisis, when the East Germans unexpectedly built a wall through and around the city to seal off their side from the West.

They were to be available for U.S. troops that would be airlifted to Germany, should another crisis occur. After collecting the materiel, the 2d Armored met up with elements from the U.S. Seventh Army, the field command in Europe, for a week-long NATO exercise that simulated an attack along the border between East and West Germany. The exercise took place in West Germany between Darmstadt to the south and both Marburg and Hersfeld to the north. V Corps, under the command of Lt. Gen. Creighton W. Abrams, served as higher headquarters for both sides. Abrams was also the exercise director.

The 3rd Infantry Division played the enemy (ORANGE) force. Elements of the 8th Infantry Division, the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment, and a reinforced Panzer Grenadier Battalion from the III German Corps served as the friendly (BLUE) force. Altogether, nearly 46,000 personnel, 900 tanks, and hundreds of trucks and armored personnel carriers participated. The Air Force flew 759 sorties in support as well. Ultimately, BLUE proved victorious, but not before it was nearly overrun by ORANGE and suffered heavy damage in the partially choreographed battles.

In conjunction with the actual exercises, VII Corps, which operated along the West German/Czechoslovak border to the south of V Corps, conducted a command post exercise. The Corps simulated the steps it would take in an emergency, when the 4th Infantry Division and support elements would deploy rapidly to its zone from the United States, collect prepositioned equipment, and conduct operations.

Following the exercises in the north, troops there returned the prepositioned equipment, performed maintenance, and rested a few days. Some units participated in live-fire exercises. Between November 12 and 21, most of the U.S. based force redeployed stateside, but about 550 personnel remained to assist Seventh Army with repositioning and repairing the weaponry. The last soldiers returned home by December 4, two weeks ahead of schedule. The initial cost for the exercise was $5.8 million, but later estimates that included payments to Germans for property damage ran $9 to $20 million.

In terms of its fundamental objective -- to deploy a large force quickly overseas that would collect prepositioned equipment and use it in field exercises -- many experts at the time considered BIG LIFT a success.

In a speech slated for November 22, President Kennedy planned to tout it as proof that the nation was "prepared as never before to move substantial numbers of men in surprisingly little time to advanced positions anywhere in the world."

The address, however, was never given. Earlier that day the president was gunned down by an assassin. Not everyone concurred with Kennedy's broader assessment of the effort. Some observed that the Seventh Army had to devote tremendous resources to prepare the prepositioned equipment for the exercises; that these weapons -- mostly older M48 tanks and M-59 armored personnel carriers -- were obsolete; that the deploying units had months to plan for the event; and that they had been able to augment their staffing some 30 percent above normal.

Because of this, critics claimed, BIG LIFT was not an accurate test of strategic airlift. General Paul L. Freeman, Jr., Commander, U.S. Army, Europe in 1963, later referred to it as the "big hoax." In spite of these concerns, the underlying concept behind BIG LIFT became a cornerstone of U.S. military strategy during and following the Vietnam War. In 1968, the Army moved two brigades and support units stateside where they were to be available for rapid deployment to Europe during an emergency.

To maintain their readiness, the military (beginning in 1969) held regular exercises dubbed REFORGER (Redeployment of Forces to Germany) during which the troops were airlifted to Europe, collected prepositioned equipment, and participated in NATO field exercises, much as had occurred during BIG LIFT. These exercises demonstrated the capability, strength, and resolve that helped the United States and our NATO Allies eventually to win the Cold War.

ABOUT THIS STORY: Many of the sources presented in this article are among 400,000 books, 1.7 million photos and 12.5 million manuscripts available for study through the U.S. Army Military History Institute (MHI). The artifacts shown are among nearly 50,000 items of the Army Heritage Museum (AHM) collections. MHI and AHM are part of the: Army Heritage and Education Center, 950 Soldiers Drive, Carlisle, PA, 17013-5021.

Social Sharing