If you’ve ever spent time around Table Rock Lake when the lake level is high after repeated heavy rainfall events, you may have noticed something curious. The water levels here start dropping before you see any change at nearby Beaver Lake or even the massive Bull Shoals Lake downstream.

The gradual drop in lake levels after reservoirs fill up might seem random, but it’s part of a deliberate pattern. Behind this carefully managed drop lies a story of geography, topography, engineering and a flood control strategy that protects thousands of people across northwest Arkansas and southern Missouri.

Although Table Rock has more storage than Beaver, it also receives more uncontrolled local runoff, meaning it will fill up nearly twice as fast for the same storm. This makes lowering Table Rock’s flood pool first, a priority.

VIEW ORIGINAL

White River Water Control

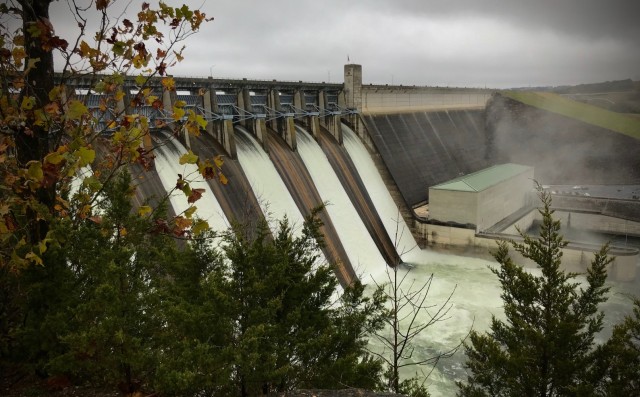

Table Rock, Beaver and Bull Shoals are three of five major flood control reservoirs located along the White River, each serving multiple roles. These include reducing flood risks, generating hydropower, supplying drinking water and offering popular spots for recreation. These three lakes sit like steppingstones along the main river’s path and work together as a coordinated system. The other two reservoirs, Clearwater and Norfork, also provide these important benefits but sit outside the main stem of the White River.

However, anyone familiar with lake level changes may notice a pattern: Table Rock tends to be drawn down first, well before Beaver and Bull Shoals. This is not a coincidence, it’s a deliberate part of a larger flood risk management strategy controlled by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Little Rock District.

The water control plan behind reducing floods in the White River Basin centers on Table Rock. Beaver, located near Rogers, Arkansas, is the first and most upstream reservoir in the chain. Farther downstream sits Table Rock near Branson, Missouri, followed by Bull Shoals near Mountain Home, Arkansas. During heavy rains, water flows downhill through this system, filling Beaver first, then Table Rock, and finally Bull Shoals.

That order is critical. Releasing from Beaver too early pushes the problem downstream before the system is ready to handle it. To prevent that, between heavy rains, engineers intentionally lower Table Rock’s levels faster than Beaver’s or Bull Shoals’. This “first to fall” strategy gives Table Rock room to catch rising floodwaters, helping prevent the river from spilling over its banks and threatening communities downstream.

VIEW ORIGINAL

If Table Rock didn’t make space first, additional water from Beaver could overwhelm the system, leading to dangerous flooding both locally and further downstream near Bull Shoals.

Table Rock acts as the middle "catch basin" in the chain due to its central location. Beaver releases water upstream, Table Rock absorbs that flow in the middle and Bull Shoals manages what remains downstream.

If USACE were to empty Beaver before Table Rock, it would disrupt this delicate balance. Since Beaver is upstream, any large release from it flows directly into Table Rock. If Table Rock hasn’t been drawn down enough to receive that surge, it could quickly reach capacity, forcing emergency releases and increasing flood risk downstream.

The same principle applies to Bull Shoals. As the final reservoir in the chain, it’s designed to hold water from both Beaver and Table Rock. If Bull Shoals is lowered too early, it may begin to refill rapidly once inflows arrive from upstream. Without careful timing, it could lose the ability to buffer floodwaters and be forced into high-volume releases, threatening downstream communities.

That’s why preserving Bull Shoals’ capacity, and managing Table Rock first, is essential. The system operates best when floodwaters are passed downstream in a controlled, stepwise fashion, maintaining enough storage in each reservoir to adapt to future storms.

White River Flood Control Development

These lakes weren’t built all at once. The construction of the Table Rock, Bull Shoals and Beaver were authorized through a series of Flood Control Acts passed by Congress. Bull Shoals got the green light first in 1938 and was completed in 1951. Table Rock followed with authorization in 1941 and completion in 1958 and Beaver was authorized in 1954 and completed in 1966.

Bull Shoals and Table Rock were prioritized earlier because, at the time of their authorization, controlling floods closer to larger populated areas and the main river channel was urgent. Building those dams first helped reduce the most immediate flood risks downstream.

By the time Beaver was authorized in 1954, the earlier dams had already significantly improved flood control. However, as northwest Arkansas grew in the mid-20th century, especially near Rogers and Springdale, the need for more drinking water and flood protection upstream led to Beaver Lake’s creation.

Today, all three lakes work as a team, managed by hydraulic engineers in the Little Rock District. They carefully monitor water levels, weather forecasts and river flows. Their goal is to keep communities safe, provide reliable water and support power generation while preserving these beautiful lakes for recreation.

While Table Rock, Beaver and Bull Shoals form the backbone of flood control along the White River, the system as it stands today isn’t exactly what engineers originally envisioned.

Between the 1920s and 1940s, engineers collected flood data that clearly demonstrated the need for additional dams to better manage the White River Basin. As part of early flood control planning, 11 more dams were proposed. Five in the upper White River Basin and six in the Black River Basin, which feeds into the White. These projects were intended to complement the existing reservoirs by adding extra layers of flood protection and improving overall water management.

However, a combination of funding shortfalls, public opposition and logistical hurdles ultimately prevented those dams from being built.

“The dams we have now along the White River provide only about 45% of the total flood control capacity needed,” said Mike Biggs chief of hydraulics & technical services branch for the Little Rock District. “The Black River Basin is actually our largest uncontrolled area. That’s important because Newport serves as the key regulating point, everything flows down to Newport, and that’s where we manage flood stages.”

This year, the Little Rock District recorded a stage of 33.3 feet at Newport, the third highest since the dams were first built in the region in the 1940s.

This level is comparable to the historic flood of 2011 which was also driven entirely by uncontrolled flows.

In the 1950s, the regulating stage at Newport was set at 25 feet during the winter and spring, and 21 feet to 18 feet during the agricultural season. Over time, legislative changes have adjusted these stages to the current levels: 21 feet, 14 feet and 12 feet, respectively.

Because the additional dams were never constructed, the current flood control system operates without those planned buffers. As a result, managing Table Rock and the other key reservoirs has become even more critical. It’s a strong reminder that while the White River flood control system is effective, it’s far from perfect. Its continued success relies on careful coordination, real-time decision-making, and the ability to adapt to changing conditions.

So, the next time you’re standing on the shores of Table Rock Lake, watching the water slowly recede after a storm, know that you’re witnessing more than a natural cycle you’re seeing a strategy in motion. This isn’t just a lake draining; it’s a calculated move in a decades-old engineering choreography designed to shield thousands from harm.

Social Sharing