Figure 1. Soldiers with 5-7 Cavalry, 1st Armored Brigade Combat Team, 3rd Infantry Division reference a training area map with strategic annotations while planning troop movements during exercise Combined Resolve 25-2 at Hohenfels, Germany on May 17, 2025. (US Army photo by U.S. Army Sgt. Fist Class Richard Hoppe)

Friendly force information requirements (FFIRs) are a powerful tool for informing decisions throughout an operation if routinely reviewed and refined as the fight evolves. During Warfighter 25-01, the 1st Armored Division did not review the FFIR until after the mid-rotation after-action review (AAR). The division’s initial approach to operations prioritized the speed of the armored brigade combat teams (ABCT) to gain a position of relative advantage compared to the enemy. After a difficult wet gap crossing that slowed the pace of operations, the enemy established their defense. They emplaced their long-range shooters and established a robust air defense bubble. The division’s emphasized speed as a key condition for success early in the operation. The division required a change in approach, but switching objectives for subordinate units would not suffice. The staff needed to challenge the assumptions that led to the prioritization of speed. After the first few days of execution the staff better understood the enemy but needed a better understanding of the necessary friendly conditions.

Thus, the 1st Armored Division switched its rapid approach to a more deliberate conditions-based approach. The Division Artillery Brigade focused on targeting the enemy’s air defenses, which enabled the Aviation Brigade to destroy enemy artillery, which provided maneuver space for the brigade combat teams (BCT) to gain the necessary ground to jump the general support rocket battalions into their next set of position artillery areas. This cycle repeated until the enemy’s air defense bubble collapsed, which enabled the Aviation brigade to conduct a mass attack and the BCT to rapidly maneuver across large swaths of land and envelop the enemy’s position. In a deliberate effort, 1st Armored Division effectively changed its approach in using the FFIR to inform a conditions-based approach that ultimately informed the commander’s decision-making ability to make rapid, informed decisions.

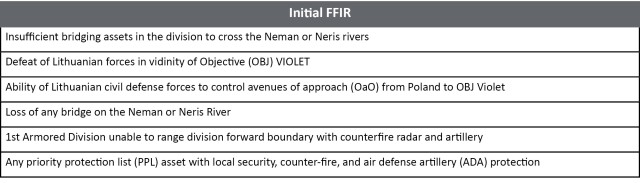

Figure 2. FFIR utilized by 1st Armored Division during the initial phases of Warfighter 25-01 (U.S. Army graphic)

The 1st Armored Division initially executed this change without deliberately readdressing the FFIR, which created a blind spot in planning and execution. The initial FFIR are listed below.

By this point in the operation, the division had already crossed both rivers and was opening a ground line of communication to our partners on OBJ VIOLET. The division conducted a daily assessment of the operation, but did not deliberately relook the assumptions made during the military decision-making process (MDMP) and determine if they needed to be readdressed.

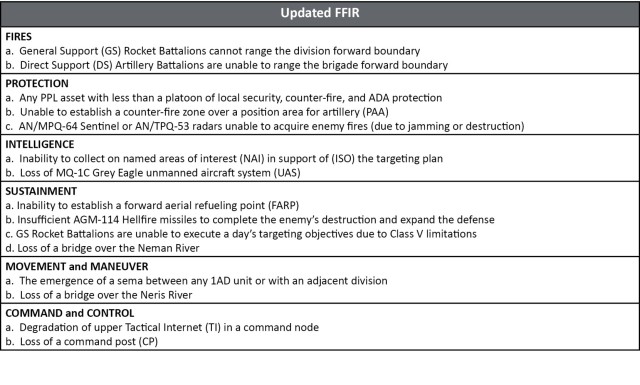

When the division’s leadership directed a deliberate reassessment of FFIR after the mid-rotational AAR, the division staff initially struggled with how to approach developing the new FFIR. After a brainstorming session, the team decided to approach it through the warfighting functions based on how the division wanted to fight. This is in line with Field Manual (FM) 5-0, Planning and Orders Production, which states, “A Commander’s Critical Information Requirement (CCIR) is specified by a commander for a specific operation, applicable only to the commander who specifies it, situation dependent and directly linked to a current or future mission, and time-sensitive.”1 The staff adopted this new approach and examined each warfighting function by risk to the overall operation. The intent was twofold, first to catch both problems that were bubbling before they erupted, and secondly to better understand if the division was positioned to seize opportunities as this would inform both the planners and current operations team to enable decisions. Additionally, the new FFIR prioritized concerns that would impact the artillery and aviation brigades over the maneuver brigades. The new FFIR are listed below:

The G35 team led the effort to develop the new FFIR, but coordinated with the functional cells for input on what would break this chain. This FFIR is not perfect and the G35 team should have included the G4 at the rear command post for better clarity on sustainment issues that could break this approach.

The enemy routinely targeted friendly air defense systems. The protection team revalidated the prioritized protection list daily through the protection working group and decision board. A whole staff approach to developing the FFIR can inform this process as it visualizes what will become more important over time and informs the PPL decisions made by the working group and decision board. A continual refinement of the FFIR would have highlighted that the key to the aviation brigade team’s operation was time on station. As the division progressed, forward aerial refueling points (FARP) became integral to increasing time on station before the aviation brigade could jump forward. There is risk associated with any decision, but prioritizing securing a FARP even if it meant pulling combat power from the close fight would have enabled the division’s ultimate rapid maneuver forward. The FFIR is not an all-encompassing list, but a forcing function to force the staff to think through how the operation will unfold and where decisions will need to be made. As the plans team develops branches and sequels the division staff need to reassess the FFIR. A properly fleshed out FFIR shows that the division staff understands the operating environment.

The FFIR is just one example of how division staff needs to relook its products throughout an operation and not assume that everything is complete with orders production. The collection manager routinely reassessed the priority intelligence requirements and associated indicators throughout the operation, but understanding the enemy is only one half of the equation when it comes to a decision. The decision maker needs to understand, “is information the commander and staff need to understand the status of friendly force and supporting capabilities.”2 The FFIR is not a stagnant product and reassessing it forces the staff to relook their running estimates and if they enable decision making.

Figure 3. Updated FFIR based on guidance obtained from FM 5-0, Planning and Orders Production (U.S. Army graphic)

This connects back to the Division’s critical path. The assessments working group (AWG) should be determining whether the assumptions made throughout the planning process remain accurate. This is in line with what the Mission Command Training Program (MCTP) recommends in their fiscal year (FY) 2023 key observations that one of the outputs of the AWG is to, “update, change, add or remove critical assumptions.”3 This assessment will ultimately inform whether the division staff will need to form a cross-functional team (CFT) lead by one of the integrating cells to address those issues identified by the AWG. The assessment working group should help the staff better understand the operational environment.4 Implicit in this is understanding the assumptions initially made during the planning process about the operational environment. The staff needs to challenge those assumptions based on the actual experience operating in that environment. This can then feed the working groups and decision boards throughout the day.

The division commander can approve the output of this staff work during the Commander’s decision board. This will inform the division commander’s understanding of the operational environment, which he can communicate to the subordinate commanders during the Commander’s visualization. A critical path that focuses on specific issues is important, but the Division staff can ‘lose the forest through the trees’ if it does not reassess its assumptions that underpinned the original plan. The FFIR is one element of the original plan that should be readdressed, but it is not the only factor that the staff should routinely readdress throughout the operation. The Division’s planners should be responsible for facilitating the reassessment of planning assumptions during the AWG, which can be split between the G5 team and the G35 team depending on the time horizon.

MAJ Christopher M. Salerno is the G35, 1AD. His previous assignments include Maneuver Captain’s Career Course Small Group Leader, Fort Moore, GA; Troop OC-T, Cobra Team, National Training Center, Fort Irwin, CA; Troop and HHC Commander, 2nd ABCT, 1st Cavalry Division, Fort Cavazos, TX; and Platoon Leader, 1-89 CAV, 2nd IBCT, 10th MTN Division, Fort Drum, NY. His military schools include Armor Basic Officer Leader’s Course; Maneuver Captain’s Career Course; and Naval War College. MAJ Salerno has a Bachelor of Science degree in Business Management from Boston College; a Master of Science degree in Organizational Leadership from Columbus State University; and a Master of Arts degree in Defense and Strategic Studies from the United States Naval War College.

Notes

1 Field Manual 5-0, Planning and Orders Production, (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 2022), 5-57.

2 Field Manual 5-0, Planning and Orders Production, (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 2022), 1-85.

3 Mission Command Training Program, “FY 23 Mission Command Training in Large-Scale Combat Operations Key Observations,”

4 Field Manual 6-0, Commander and Staff Organization and Operations, (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 2022), 4-35.

Social Sharing