In January 2022, a US combined arms battalion consisting of one headquarters and headquarters company (HHC), two tank companies, one mechanized infantry company, and one forward support company (FSC) participated in exercise Allied Spirit 22 as part of a larger multinational brigade consisting of approximately 5,000 Soldiers representing eight nations. Exercise Allied Spirit is the Joint Multinational Readiness Center’s (JMRC) largest annual exercise at Hohenfels Training Area. The Rotational Training Unit (RTU) is typically either a US or multinational division headquarters with an allied brigade headquarters serving as the primary training audience. The brigade is typically comprised of a mixture of its organic battalions, a US Army maneuver battalion, and other multinational battalions from across NATO. During this unique rotation, the lessons learned at every echelon were indispensable to building partner capacity, enhancing interoperability, strengthening relationships, and enabling NATO’s preparedness for a future armed conflict in Europe. This article aims to describe and share some of the personal friction points and lessons learned during the multinational exercise from someone who participated in the exercise as a Combined Arms Battalion S3 and who is now a current Observer Coach/Trainer (OC/T) at JMRC. The lessons learned in this article are intended for maneuver battalion field grade officers, battalion staffs, and their senior enlisted advisors who are expected to take part in future multinational operations.

Task Organization

During exercise Allied Spirit 22, the concepts of multinational interoperability were stretched to the limits during the 9-day fight in an austere large-scale combat operations (LSCO) environment. This exercise saw a unique task organization consisting of the Latvian mechanized infantry brigade serving as the brigade headquarters with the subordinate battalion headquarters consisting of a German reconnaissance battalion, a Latvian mechanized infantry battalion, a German panzergrenadier battalion, a US combined arms battalion, a German field artillery battalion, and a Latvian support battalion. Additionally, there was a plethora of multinational enablers from various nations to include a US general support aviation battalion (GSAB), a Latvian air defense battery, an Italian tank platoon, Hungarian and Spanish civil affairs assets, Hungarian and Spanish military police, Dutch engineers, Lithuanian engineers, and a Lithuanian chemical platoon to name a few along with many others. The interoperability challenges at all levels from squad to brigade were numerous and wide reaching and provided an excellent learning laboratory in the fight against the infamous JMRC Opposing Forces (OPFOR).

For a unit planning on conducting multinational operations, leaders must look at how the organization will conduct the full operations process (plan, prepare, execute, and assess) through the lens of the three dimensions of interoperability: human, procedural, and technical. Though there have been many efforts to standardize operations and terminology amongst NATO members, there will still be inherent differences that leaders must work through at every level.

Multinational Interoperability: The Human Dimension

The human dimension is the bedrock and foundation to interoperability and is by far the easiest to get right. On the contrary, if the human dimension is done poorly, it can be disastrous. The human dimension is built on solid interpersonal relationships defined by mutual respect and a healthy dialogue. Mastering this domain requires time, effort, and patience to overcome language and cultural differences. If time allows, any pre-operational training or team building events should be maximized to better foster personal relationships. When all else fails, the human dimension will overcome any temporary gaps in the procedural and technical dimensions.

Figure 1. Key leaders from Latvia, Germany, and the US huddled around a map while operating in the JMRC box at Hohenfels Training Area as they discuss positioning for the defense. (Photo by Savannah Miller)

During the five months leading up to exercise Allied Spirit 22, as part of the US rotational force deployed to Lithuania within Operation Atlantic Resolve, the US battalion took advantage of its proximity to Latvia by sending multiple platoons and companies to conduct periodic training in Latvia. In October 2021, JMRC held the in-person Leader Training Program (LTP) event for Allied Spirit 22 and this venue provided an excellent opportunity for the multi-national participants to get to know each other, provide capabilities and limitations briefs, and develop a baseline understanding of the Latvian Brigade Commander’s intent. Over the course of the five months, strong relationships developed between the battalion leadership and the Latvian mechanized infantry brigade. These relationships were further solidified when the battalion sent a company team to Latvia to participate in a month-long Latvian training event that included live fire exercises at every echelon from platoon to battalion. In addition to developing relationships with the Latvians, the training schedule allowed for relationships to develop between the battalion and the US Army Security Force Assistance Brigade (SFAB) team assigned to the Latvian Brigade headquarters. Knowing that the SFAB Team would be embedded into the Latvian Brigade’s staff during Allied Spirit 22 allowed for discussions about how the SFAB would act as a cultural, linguistic, and technical intermediary (also known as a “swivel-chair”) if needed between the battalion and the brigade headquarters. In terms of relationship building and understanding the brigade commander’s intent for operations, the battalion emphatically assessed itself as well trained. With this, came the confidence that any challenges could be overcome with strong relationships.

However, the rotation exposed some of the holes in that thinking and preparation. During the reception, staging, and onward movement phase (RSOM), the brigade headquarters, unable to control the equipment arrival timelines for so many nations struggled to synchronize the generation of combat power. The result was that the brigade “powered down” the generation of combat power to each subordinate battalion. With the delayed arrival of one of the battalion’s trains that contained a significant number of Abrams and Bradley Fighting Vehicles (BFV), the battalion struggled to generate enough combat power to move into the assigned tactical assembly area (TAA) and then to the subsequent battle positions (BPs) as planned. Since the brigade headquarters had already moved into the Area of Operations (AO), the battalion’s “top 5” were challenged with the cultural and language barrier to articulate the friction and the risk to mission associated with deploying into “the box” in a piecemeal fashion.

Therefore, to prevent the embarrassment of a US unit not crossing the Line of Departure (LD) on time, the decision was made to deploy the battalion’s scout platoon as quickly as possible with what little combat power was available. That night in the middle of a snowstorm, the battalion scout platoon crossed LD with only five gun-trucks, none of its BFVs, and without artillery or mortar assets in position to support. Additionally, since the battalion tactical command post (TAC) and the main command post (CP) were not yet functional, the element deployed into the fight with no ability to communicate with the brigade headquarters or any adjacent units. The lead element was misdirected into some restricted terrain which in-turn led to a fueler being rolled-over. The decision was then made to halt movement for the night and wait until morning to try and get the lead elements into position.

Over the course of the next three days, the battalion struggled to get its combat platforms into the BPs to establish the defense. This lack of ability to project combat power forward resulted in a very significant gap in the brigade’s defensive line, which in turn caused a significant amount of friction across the brigade as its staff tried to figure out how to best close the gap and prevent enemy penetration.

There are several lessons I learned from those first three days of chaos, in particular the importance of mutually understanding the capabilities and limitations, the importance of liaison officers (LNO), how to put pride aside, and the importance of paying attention to the details in multinational sustainment operations.

Regarding spotty radio communication, I expected the Latvian leadership to inherently understand how a combined arms battalion fights. The battalion’s inability to articulate how conditions were not yet set was largely due to the fact the battalion staff was simply not used to dealing with an allied headquarters. Key leaders, including myself, wrongly assumed the Latvians would be able to see the problems as Americans saw them. Additionally, the battalion staff officers never went in person to provide their brigade staff counterparts with a recommendation for how to adjust the plan to cover the frontage gap with those battalions already in the box to enable our battalion to finish generating combat power.

Another lesson I learned was that even though LNOs were assigned to adjacent battalions, a battalion LNO was never assigned to be in the brigade main CP; and thus, the battalion staff relied too heavily on the SFAB to articulate any concerns. Even though the SFAB team was made up of an exceptionally talented group of Soldiers that worked tirelessly to assist the battalion, the team did not have as much of an intimate understanding of capabilities and limitations as a leader from our own formation would have. Admittedly, we did not want to swallow our pride and say that we were not ready to fight. Had we not been so concerned about the image of a US Army unit not making LD, the result would not have been such a massive desynchronization of the brigade. This in turn would have allowed the brigade to cover the battalion’s gaps and enable the setting of conditions for a concentrated deployment into the AO.

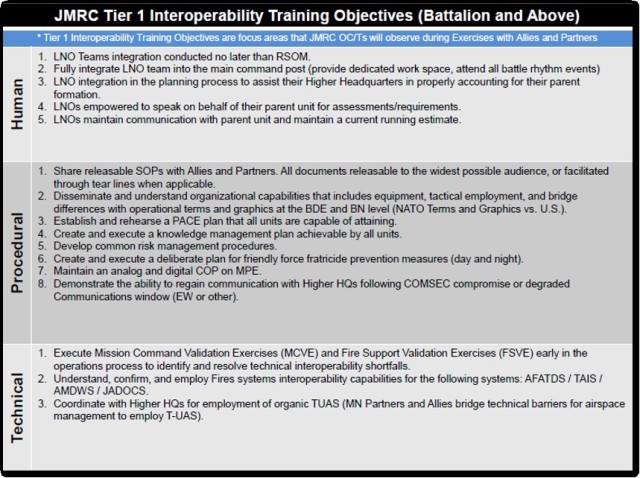

Figure 2. Allied Spirit 22 Interoperability Training Objectives (U.S. Army graphic)

Finally, during RSOM a more concerted effort should have been made to ensure the battalion’s sustainment warfighting function was fully communicating with the brigade S4 section and articulating the challenges and any required assistance during routine touchpoints. Regardless of the challenges faced in the human dimension, the solid relationships that were built prior to the exercise were relied on to make the mission happen despite the significant friction faced in the other two dimensions.

Multinational Interoperability: The Procedural Dimension

The procedural dimension encompasses “the how” of planning, preparing, and executing for all things of a warfighting nature. This dimension includes how units absorb and operate in accordance with standard operating procedures (SOP) as they relate to various aspects of doctrine. Inevitably, there will be differences in operational terms and graphics, definitions, planning processes and steps, briefing techniques and expectations, knowledge management methods, orders production and dissemination, rehearsal constructs, risk mitigation, fratricide avoidance, national agreements and caveats, and command and control procedures during execution.

As previously mentioned, during the five months leading up to the rotation, the battalion focused heavily on sending tank and infantry platoons to Latvia to train with that brigade. As a result, the company-grade maneuver leaders gained valuable first-hand knowledge of the capabilities and limitations of our Allies. These leaders became intimately familiar with the challenges inherent in a multinational task organization and developed sound training plans in preparation for the rotation. However, at the battalion-level there was a lack of emphasis to integrate the battalion headquarters and the forward support company (FSC) into those training events; nor was there a full appreciation for how the Latvian brigade staff would conduct the operations process.

The battalion’s key leaders quickly realized that the Latvian brigade headquarters did things very differently than what the US Army is accustomed to. With so many different units and so many ways of doing things, the Latvian brigade commander decided that he was going to pull in the battalion commanders and personally plan each phase of the operation. On the evening of the exercise’s third night, the battalion commanders and operations officers were summoned to the brigade plans tent to receive what we thought was going to be an operations order (OPORD) brief in preparation for an attack in two days. Instead of an OPORD brief, the battalion commanders gathered around an analog map for a three-hour council of war session to conceptually discuss each unit’s proposed actions during the attack. Once everyone came to an agreement, the brigade operations officer intended to codify everything that was said into a written order to be published over a secure system that would synchronize the operation with digital graphics being provided to each battalion. Obviously, this was very different than the typical OPORD brief that US Army leaders are accustomed to.

Figure 3. Key leaders from Latvia, Germany, and the U.S. huddled around a map while operating in the JMRC box at Hohenfels Training Area as the multinational brigade prepares for the final attack. (U.S. Army photo by CPL Uriel Ramirez)

Subsequently, the battalion staff’s unfamiliarity with the Latvian knowledge management process and naming conventions, caused the staff to lose precious planning hours as staff officers could not ascertain which order they were looking at due to the unfamiliar naming conventions that were being used. Once the correct OPORD was attained, it was found to be an exceptionally large document that was written in accordance with NATO standards, but it included terms and graphics that were formatted in a manner that the battalion staff had never seen before. This unfamiliarity caused the staff to lose even more precious time in trying to analyze what was written. Additionally, the OPORD was overly vague and came with minimal PowerPoint graphics that had unfamiliar intent symbols and markings. The written portion included minimal details regarding time and distance analysis, triggers, sustainment, and intelligence and fires synchronization. Realizing the battalion staff had to hurry and begin planning since the combined arms rehearsal (CAR) would be the next morning, the staff quickly went through a session of the military decision-making process (MDMP) to issue a battalion OPORD later that night.

The next morning as the key leaders arrived for the brigade CAR, we were surprised to see once again the battalion commanders being pulled around a table to go through another council of war in the exact same manner as the day prior. Once again, each commander discussed in vague terms the actions his battalion would take. The brigade commander would then initiate a wargame to discuss branch plans and sequels over the map. Once again, the brigade staff developed a second, full OPORD and issued it in the same manner as before. Taking the lesson learned from the previous day, this time we made sure to trace a copy of the brigade’s analog graphics so that we had the same common operating picture as the brigade staff. Their system for planning was clearly different than anything we had seen before.

From this experience came multiple lessons learned regarding procedural interoperability. First, I should have exposed the battalion staff to NATO doctrine, terminology, and orders formats beforehand to avoid the lost planning time it took to decipher the orders during the stress of the fight. Secondly, the battalion staff should have had a better understanding of the higher headquarters’ knowledge management processes and naming conventions so that time wasn’t wasted either looking for the order or planning off the wrong document. Third, this was another example of the importance of having an experienced LNO at the brigade headquarters who should have also been involved in planning on our behalf. Had an LNO been dedicated to the brigade headquarters, he could have gathered the OPORD, gotten copies of graphics, and prepared the battalion staff for the expectations and briefing formats for the key leader touchpoints. Fourth, had questions been asked about how the brigade staff conducts the planning process, the battalion staff would have been better prepared to initiate parallel planning with minimal guidance as the brigade conducted their planning. Fifth, the focus of the commanders’ dialogues was largely centered around maneuver and fires. However, since most of the multinational formations were either light, motorized, or made of light tracks, they had little experience in sustaining a large combined arms battalion over that length of time.

There was little consideration for ammunition and fuel resupply across the brigade’s AO. During the entire rotation, the battalion was severely hindered by sustainment across all classes of supply and had the battalion staff known the structure of the meetings (specifically the warfighting functions synchronization meetings), the battalion S4 would have been better prepared to pose the question of how sustainment was going to be conducted across the brigade. With that understanding, he could have offered sound recommendations to the Brigade S4 along with the Latvian Support Battalion based on everyone’s collective experiences. Additionally, the battalion should have integrated its FSC into the Latvian Support Battalion’s planning process and an LNO should have been assigned to be co-located into their battalion headquarters. Finally, if I had better understood how the brigade commander and his staff intended to synchronize operations, I could have provided recommendations for detailed graphic control measures that were tied to terrain features instead of intent symbols to maximize combat power at the brigade’s decisive point and avoid fratricide. Though the maneuver companies had spent a great deal of time conducting vehicle identification, the risk of fratricide was exponentially elevated with multinational units being task-organized at the platoon and company-levels.

Multinational Interoperability: The Technical Dimension

The technical dimension focuses on the ability to communicate through the various systems and equipment required to conduct operations. These systems include voice and digital systems and must consider the capabilities and limitations of radios, computers, global positioning system (GPS), fires networks, and airspace coordination systems all while trying to ensure security and reduce digital signatures to avoid enemy targeting. Without an ability to communicate effectively and securely, a multinational organization will risk quickly becoming desynchronized and unable to react to the changing conditions on the battlefield.

By and large, the battalion at echelon struggled the most with the technical dimension. Critically undermanned in the battalion S6 section, the battalion was consistently challenged with communications. Due to the incompatibility of the ASIP radios with the Latvian higher headquarters, two Tactical Satellite (TACSAT) radios were used to effectively communicate with the brigade headquarters. However, for the adjacent units, the battalion staff relied heavily on some rather inexperienced officer LNOs acting as a swivel chair within the adjacent battalion headquarters. Though the battalion staff was able to communicate, the language and cultural differences coupled with too many “communicators” made the conversations ineffective. This inability to conduct rapid and efficient cross coordination with adjacent units added to the de-synchronization of the brigade and an inability to gain a true intelligence picture of enemy actions on the ground.

The lack of preparedness and training for the battalion staff and companies on how to properly fill radios with the correct encryption caused constant issues. The S6 section experienced challenges with conducting retrans operations as the lack of pre-combat checks (PCC) resulted in missing equipment that left the battalion unable to deploy the battalion retrans section until the seventh day of the exercise. Additionally, none of the Joint Battle Command-Platform (JBCPs) had the proper US Europe Command (EUCOM) image as they still had the US image from before the deployment, therefore, they were incompatible for operations in Europe. Not to mention, because of one printer being broken during the movement into the area of operations (AO), the battalion staff had to rely on runners and face-to-face conversations with hand-written OPORDs and manually drawn graphics to synchronize all battalion operations.

On top of the communications friction, the relentless OPFOR pressure forced the staff to jump the main CP multiple times. Since the training plan had not placed a significant amount of emphasis on procedures for setting up and tearing down the main CP, Soldiers were relatively inexperienced at this task, and it only complicated the communications problem-set. Initially, the main CP was internally and externally robust and took too long to establish, however, it was quickly learned that the key to rapid emplacement and displacement centered around non-commissioned officers (NCOs) developing a systematic process to efficiently pack and unpack the minimum essential items to establish a small and mobile main CP.

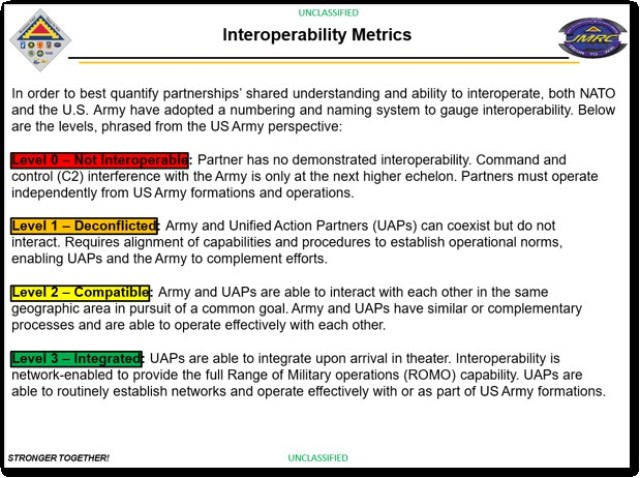

Figure 4. Allied Spirit 22 Interoperability Metrics (U.S. Army graphic)

As in the other two dimensions, the key lessons I learned in the technical dimension were numerous. First, more emphasis should have been placed on experimenting with how to bridge the gap with technical compatibility. I should have established a communications working group to garner lessons learned from other organizations such as the Tactical Voice Bridge, the Android Tactical Assault Kit (ATAK) “Green Kit” (which is a series of components and devices used to bridge the communications gap between the different Allied radio systems), or looked at cross-leveling from within to distribute frequency modulated (FM) Radios to the higher headquarters and adjacent units. Second, regarding PCCs and pre-combat inspections (PCIs), instead of taking a myopic approach by focusing our attention on equipment for the individual Soldier and the combat fighting platforms, we should have prioritized the inspection and packing of the main CP along with the radio equipment and retrans systems. Third, the training plan should have placed a larger emphasis on conducting maintenance on communications systems and forced the platoons to send JBCP messages during motor stables. Also, the battle rhythm should have made it routine to setup both the internal and external main CP to build repetition and to identify shortages and place them on order with enough lead time before the exercise. Lastly, key leaders should have had extensive discussions with the rest of the brigade leadership on the command & control architecture and fully discussed the procedures we would execute for various contingencies, such as communications security (COMSEC) compromise and jamming.

Conclusion

By the end of the 9-day exercise, the battalion as a whole gained an education in multinational interoperability and took home countless lessons learned in the human, procedural, and technical dimensions from which to build follow-on home station training plans. More importantly, the challenging exercise solidified an incredible bond between the Allied units that participated in the exercise, and it gave our Soldiers a concrete understanding of what it means to fight alongside Allies in large scale combat operations. Despite the challenges, I learned the greatest lesson: that leaders must work exorbitantly hard to build and maintain relationships with our Allies during training; so that when everything is going wrong and systems start failing, simplicity and teamwork will get us to the objective and win. Hopefully, these lessons will prevent your unit from making the same mistakes.

MAJ Chris Perrone is the Deputy Task Force OC/T for the Timberwolf Team at the Joint Multinational Readiness Center (JMRC) in Hohenfels, Germany. His previous assignment was as a combined arms battalion operations officer and executive officer in the 1st Infantry Division, Fort Riley, Kansas.

Social Sharing