On the eve of the 2023 Ukrainian counter-offensive, analysts viewed the operation as at a crossroads: “The next phase of the war will hinge, in part, on the ability of Ukrainian forces to retake territory by moving from attrition to maneuver warfare and to shift the offense-defense balance in favor of the offense.”1 From June to November 2023, however, multiple Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) brigades failed to penetrate the Russian Surovikin line along the Orikhiv-Tokmak Axis in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, advancing approximately 20km at the cost of 518 vehicles, including 91 tanks and 24 engineering vehicles.2 The wake of the failed 2023 Ukrainian counter-offensive left more than the loss of life and equipment. It reinforced the notion currently in vogue that maneuver warfare is dead.3

At the core of the current maneuver-attrition debate is the ability - or inability - of units to successfully execute the combined arms breach. This article uses the 2023 Ukrainian counter-offensive as a case study to reveal challenges for the Armored Brigade Combat Team (ABCT) in applying the US Army’s five breaching tenets on the modern battlefield. The AFU’s experience demonstrates the vital importance of detailed intelligence and appropriate task organization. The failed counter-offensive also highlights difficulties in applying the breaching fundamentals known as “Suppress, Obscure, Secure, Reduce, Assault (SOSRA),” synchronization, and mass within in the operational environment the AFU faced. Although the ABCT will fight within a different operational context, identifying Ukrainian challenges in applying the breaching tenets will enable its leaders to develop tactical and technical solutions to succeed in Large-Scale Combat Operations.

Russian Obstacles: The Enduring Importance of Detailed Intelligence

Following the AFU’s offensives which recaptured Kharkiv and Kherson Oblasts in 2022, the Russian Armed Forces (RAF) began construction of a complex defense system in Zaporizhzhia Oblast. By April 2023, the RAF defense system consisted of three major sub-systems, spaced 10km to 20km apart to prevent another breakthrough. After more than six months of preparation, the first two defense sub-systems were nearly identical.4 The third sub-system, however, resembled more of a constellation of disconnected fortifications. Here, the RAF prioritized resources to secure key terrain such as Tokmak, where they constructed defenses along its entire perimeter.5

Prior to the AFU’s counter-offensive, open-source reports described the composition of the first two sub-systems as: dragons teeth laid out in three rows; 300m to 500m of open area heavily mined; irregular trenches that support both infantry and vehicle fighting positions as well as dugouts and vehicle hide sites; another 300m to 500m potentially mined open area usually containing a woodline or other concealed area to enable resupply, observation posts, and anti-armor firing positions; and an anti-tank ditch with a three-layered dragons teeth obstacle immediately behind.6 These estimates focused on trenches and anti-tank ditches and only mentioned minefields. Nevertheless, RAF doctrine stated that engineers should emplace anti-armor minefields “200-300 meters wide and 60-120 meters in depth with four rows per minefield.”7 In the end, positions are held by soldiers, and analysists hoped poor RAF warfighter quality and morale would assist AFU operations. Accordingly, Ukrainian Brigadier General Oleksandr Tarnavskyi task organized the newly-created 47th Mechanized Brigade as the breach force in part due to its high morale, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) training, and Western equipment.8

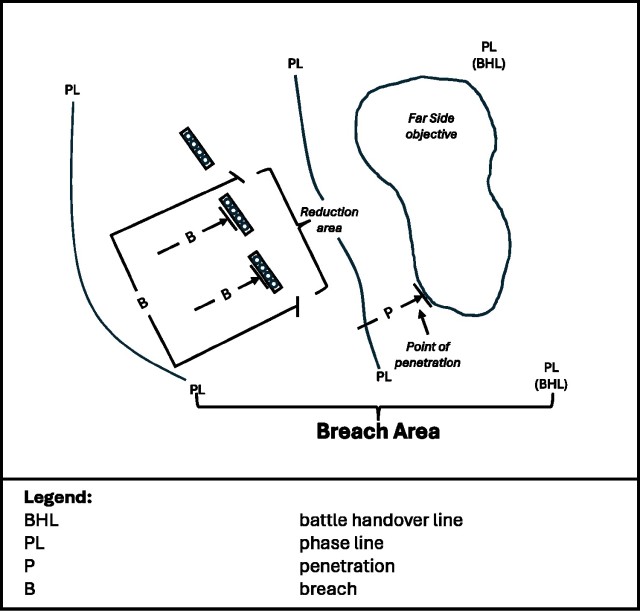

The location for the first breach area lay north of the village of Novodarivka because the minefields were less dense in this sector.9 Although the AFU’s intelligence estimate remains classified, Ukrainian leaders certainly miscalculated. Regarding the battlefield situation his unit encountered, Lieutenant Colonel Oleksandr Sak, the commander of the 47th Mechanized Brigade, stated, "Judging by the actions taken on 4 June 2023, the breach force maneuvered to the point of breach shrouded by the fog of war."

The subsequent failed breach at Novodarivka underscores the importance of detailed intelligence prior to conducting a deliberate breach against a determined enemy. Terrain analysis remains a fundamental element to maneuver planning, and information collection must holistically account for all aspects of complex obstacles. The depth of Russian obstacles required mixing several collection systems and employing multiple methods of reconnaissance to enable the breach force. Regarding mines in particular, critical information to collect includes location, composition, orientation, frontage, depth, types, fuses, and methods of employment.11 The AFU could collect on the point of breach but did not adequately collect on the length of the breach area. Although some AFU unmanned aerial system (UAS) operators had success identifying surface-laid mines through UAS electro-optical or thermal sensors, they could not identify buried or stacked mines, mines with non-metallic casings, mines in areas with considerable metal battlefield debris, and during thermal-crossover. In response, the AFU procured commercial UAS equipped with ground penetrating radar to survey sub-surface areas with some benefit.12

The discussion above only serves to demonstrate a current training and capability gap. The ABCT should integrate complex obstacle reconnaissance within training and experiment with commercial UAS equipped with ground penetrating radar. Commanders and their staffs at echelon should expect to request and integrate higher headquarters’ assets into collection plans to enable breaching operations. The failed breach is a sobering reminder that the breaching tenet “intelligence” cannot be reduced to obstacle intelligence, however. Thorough analysis of the enemy capabilities, composition, disposition, and courses of action are critical to support combined arms breach planning. Reconnaissance by fire can validate obstacle intelligence, cause the enemy to unmask assets, and enable the maneuver commander to assess how and how hard the enemy will fight. Most importantly, no unit should cross the line of departure without a near real-time intelligence update. Technology and tactics will continue to evolve, but the problem set of gathering accurate intelligence for the entire length of the breach area will remain.

Figure 1. Breach Area from ATP 3-90.4 Combined Arms Mobility, 10 June 2022 (U.S. Army graphic)

Appropriately Task Organize

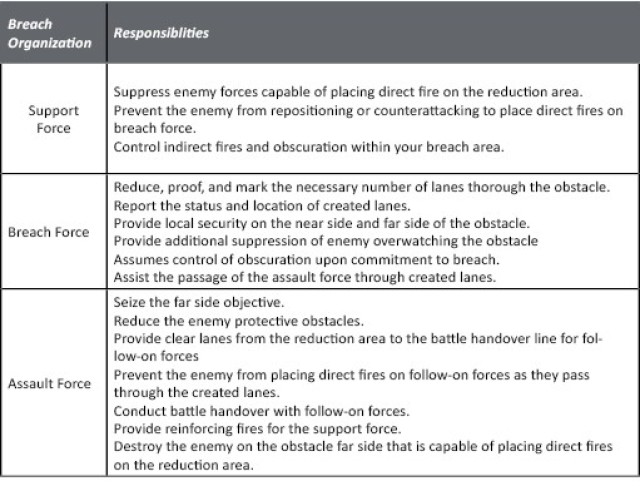

To apply the breaching fundamentals, the ABCT forms three task organized units to conduct a combined arms breach, namely the support force, the breach force, and the assault force.13 The support force isolates the reduction area and suppresses the enemy with direct and indirect fires.14 The breach force’s main purpose is to reduce, proof, and mark lanes through the enemy obstacle.15 Finally, the assault force destroys the enemy on the far side of the obstacle and seizes the far side objective (see Figure 2).16 The size and composition of each unit is determined through reverse planning, meaning units first determine the assault force requirement, then the requirements for the breach and support forces, respectively.17

Although the 47th Mechanized Brigade’s complete task organization remains classified, Novodarivka and Rivnopil were the initial objectives and Robotyne was the final objective for the brigade to seize within the first 48 hours of the counter-offensive.18 Since the first two breach attempts failed, the planned composition of the assault force is unknown. The AFU committed a company-sized breach force consisted of two mine clearing vehicles, a section of Leopard 2A6 tanks, a platoon of M2A2 Bradley Fighting Vehicles, and four Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles (MRAPs) to create a single lane.19 Being wheeled vehicles, the MRAPs struggled to follow the tracked mine clearing vehicles and tanks and “several of the MRAPs bogged in, while the cleared lane was insufficiently wide for other vehicles to pass.”20 When the MRAPs began to become mired in the breach, two RAF tanks engaged the breach force at 800m. Surprisingly, there was no support force, and the AFU instead relied upon indirect fires to suppress the RAF defenders. Thus, each vehicle was destroyed before AFU dismounts destroyed the RAF tank section.21

With one company team immobilized in the breach, the AFU committed a second company team of similar composition to breach west of the first attempted breach area. Although the ground was firmer, an additional RAF tank section maneuvered on the breach force. The brigade command post watched the engagement via UAS feeds and employed indirect fires to disrupt the RAF tanks. Attempting to increase tempo, however, the AFU breach force did not proof or stay within the lane, causing every vehicle to become immobilized.22

Figure 2. Support, Breach and Assault Force Responsibilities from ATP 3-90.04, Combined Arms Mobility, 10 June 2022 (U.S. Army Graphic)

As seen above, the AFU did not properly assess the enemy or terrain. This led AFU leaders to form company teams with vehicles with different mobility restrictions, in turn causing these units to lose tempo in the breach. Mine clearing vehicles deployed mine clearing line charges (MICLICs), but the density and depth of the minefield was greater than AFU intelligence estimates. Thus, the breach force was not properly weighted. The failed breach attempts also highlight the requirement for the support force to effectively isolate the entire breach area with direct fires. The first 24 hours of the counter-offensive tragically demonstrates the importance of appropriate breaching organization.

Challenges to Integrate SOSRA

Leaders integrate the breaching fundamentals within the planning and execution of breaching operations. Frequently referred to by the mnemonic “SOSRA,” the breaching fundamentals consist of suppress, obscure, secure, reduce, and assault. The Ukrainian seizure of the Rivnopil shows the successful application of the breaching fundamentals to an operation. Nevertheless, the operational environment, to include RAF adaptation and Western equipment shortfalls, challenges the ability of US forces to successfully integrate SOSRA into breaching operations.

After nearly a week of fighting, the 47th Mechanized Brigade secured Novodarivka. AFU leaders determined that seizing Rivnopil, located due east of Novodarivka, would be necessary to secure IX Corps flank before continuing to advance south.23 The previous breaching attempts around Novodarivka had led to two companies’ worth of vehicles, to include 60% of Ukraine’s mine clearing equipment, becoming non-mission capable.24 Thus, the 31st Mechanized Brigade leaders decided on a different approach.25

Figure 3. B 1-37 AR conducts training with tank mounted mine clearing equipment in Grafenwoehr Training Area, February 2024 (Photo by CPT Samuel Parker)

As the support force maneuvered to the breach area, an AFU artillery battery provided suppression. An AFU tank section established an attack by fire position and began to engage RAF fighting positions. The defending RAF company was therefore suppressed both by indirect and direct fires. The 31st Mechanized Brigade then employed smoke to obscure two AFU infantry platoons maneuvering in squad-size elements along a treeline to the east of the objective. Believing this to be the breaching force, the RAF oriented on the infantry. Meanwhile, a third infantry platoon executed a covert breach west of the objective, reducing obstacles and creating multiple dismounted lanes. By causing the RAF company to orient away from the breach area and increasing their artillery rate of fire, the AFU support force successfully secured the breach area. After completing the breach, the AFU infantry platoon transitioned from being the breach force to the assault force to maintain the initiative.26 The RAF company rapidly retrograded from their defenses, and the 31st Mechanized Brigade passed forward the 36th Marine Brigade which seized Rivnopil.27

By the end of June, the RAF began to adapt their tactics. First, the RAF departed from their doctrine concerning minefield depth, increasing the standard depth from 120m to 500m. The RAF also deliberately constructed obstacles to destroy mine clearing equipment to include stacking multiple anti-tank mines to increase net explosive weight and placing containers of napalm approximately every 18m across and 40m deep.28 A translated RAF after action report dryly noted that after encountering incendiary land mines, “the [AFU] offensive resumed only after 3-4 days, while its intensity, composition of forces and funds decreased.”29 Additionally, the RAF increased the use of loitering munitions such as the Zala Lancet to target armored vehicles as well as increased the density of UAS to provide redundant sensing.30 Attack aviation was also relocated closer to the forward line of troops and placed on a 30 minute alert status.31 Finally, RAF electronic warfare (EW) assets proliferated to both limit AFU communications and protect RAF from AFU UAS.32

Due to many factors to include multiple failed breaches, RAF adaptation, lack of air superiority and UAS proliferation, and finite manpower, ammunition, and equipment, AFU leaders shifted from company teams conducting mechanized combined arms breaches to dismounted sapper teams reducing obstacles.33 Senior Ukrainian leaders such as General Valerii Zaluzhnyi believed the solution to restore maneuver lay in technology.34 Technological solutions, however, result in counter-measures. As military analyst Stephen D. Biddle asserts, “Force employment had played a more important role than either technology or preponderance for twentieth century warfare.”35 Therefore, although military hardware matters, doctrine will have a greater role in enabling success on the battlefield.

ATP 3-90.4 Combined Arms Mobility states “the purpose of suppression during breaching is to protect forces that are reducing obstacles and maneuvering through the reduction area.”36 The RAF defense of Novodarivka demonstrates the need for direct fire suppression throughout the depth of the breach area and the value of counter-battery fire. Perhaps due to the examples listed in doctrine, leaders tend to focus on direct and indirect fires, neglecting the role of non-kinetic fires to disrupt enemy command and control. Non-kinetic fires can also facilitate the suppression of enemy air defenses, which enables friendly air support during the breach if air superiority is not achieved. Thus, commanders and staffs must leverage capabilities in multiple domains to achieve suppression.

More significantly, however, US Army breaching doctrine overlooks the role of shaping actions prior to suppression. Between the decision to breach and the execution of the breach, maneuverists must identify enemy critical vulnerabilities and exploit them. Prior to initiating their attack on Rivnopil, the AFU targeted RAF lines of communications. Not only was RAF physical combat power eroded, but so too was their morale. The RAF company immediately retreated when the AFU assault force appeared on their western flank.37 As enemy defenses gain depth and complexity, the importance of shaping operations also increases.

Obscuration is used to prevent enemy observation and targeting.38 During the counter-offensive, however, only 3% of AFU fires missions included smoke. Smoke missions prevented AFU higher headquarters from battle-tracking and coordinating their units via UAS. Therefore, as some observers have noted, “Commanders persistently prioritize maintaining their own understanding of the battlefield over laying down smoke and concealing their personnel’s movements.”39 Mission command and proficient staffs enable decentralized command and control. The larger challenge for the ABCT is to generate sufficient smoke for enough time. In addition to cannon and mortar fired smoke rounds, units must train to deploy vehicle launched smoke grenades and smoke pots. Units may also consider converting their M1 Abrams tanks to diesel fuel to safely employ the smoke generator. Significantly, the AFU demonstrated that obscuration relates not only to the physical dimension but also the mental. At Rivnopil, the AFU cleverly used smoke to deceive the RAF and conduct a covert breach. Thus, both smoke fire missions and deception play an equally important role in preventing the enemy from divining the location of the breach force.

Figure 4. U.S. Army Reserve Soldiers from the 449th Mobility Augmentation Company, 478th Engineer Battalion, 926th Engineer Brigade, 412 Theater Engineer Command, based in Fort Thomas, KY., fire an inert mine clearing line charge during a Gate III validation exercise on Fort Knox, KY., February 12, 2018 (U.S. Army Reserve photo by SFC Clinton Wood)

The proliferation of loitering munitions challenges the ability for the breach force to secure the point of breach and maintain local security on the near and far side of the breach. Suppression may limit enemy UAS operators and obscuration will degrade UAS first person viewer capability. Depending upon the frequency spectrum being jammed, counter-unmanned aerial system (C-UAS) systems may impact both friendly UAS and communications systems. Therefore, the intelligence estimate of enemy loitering munition employment is critical to enable the commander to make risk-informed decisions.

Reduction remains a challenge both for the AFU and the ABCT. Even before the RAF started to construct obstacles targeting the capabilities of mine clearing equipment, both AFU breaching forces had vehicles that were immobilized by mines in the breach at Novodarivka. As the counter-offensive progressed, RAF companies began emplacing hundreds to thousands of anti-tank mines and “stacking three TM-62M mines on top of each other specifically to destroy … the mine-rollers and trawls used by breaching vehicles and tanks.”40 Regardless of RAF counter-measures, an ABCT would be heavily challenged to reduce and proof lanes given the operational environment faced by the AFU during the counter-offensive.

The restructured US Army Engineer Battalion comprised of three Combat Engineer Company - Armored (CEC-A) brings a total of six Assault Breacher Vehicles (ABVs), each capable of firing two M58 MICLICs and equipped with either a surface mine plow or blade, as well as six trailer-pulled M58 MICLICs. Each MICLIC creates a lane 100m in length. However, if multiple MICLICs are required due to the minefield depth, an ABV moves 25m into the path created by the first MICLIC and fires its charge. This extends the lane approximately 85m, not 100m. Therefore, one lane through a 500m obstacle requires six MICLICs. Additionally, MICLICs have limited effects against multiple types of mines to include prong AP mines, magnetic mines, top-attack mines, and delay-time fuzes.41 According to a US Marine Corps study on breaching during Operation Desert Storm, MICLICs had a 60% detonation rate and left approximately 25% of the mines intact, making the proofing of lanes necessary.

M1 Abrams tank-mounted mine clearing blades (MCB) and mine clearing rollers (MCR) have their own limitations. The MCB is capable to both breach and proof lanes. It has three depth settings of 8in, 10in, and 12in, but requires 18in of soil depth to be effective; it does not perform well in rocky terrain. When the MCB is lowered, the tank should move no faster than 10 mph, and the main gun should be traversed to the side to avoid damage should a mine detonate.42 Also, the lifting straps are nylon, so wire obstacles or explosions can easily sever the straps; manually lifting the plow takes approximately 10 minutes. If the mold board extensions are damaged or missing, mines may fall into the path of the tank’s tracks.43 The MCB is a vital piece of equipment which must be mounted and trained constantly for leaders to understand their capabilities and limitations.

The MCR is used to detect the beginning of a minefield and to proof the lane. Weighing 10 tons, the MCR requires an M88 recovery vehicle for installation onto a tank. Once installed, the tank’s mobility and speed is greatly reduced, and the tank has an increased likelihood of becoming mired in muddy or soft terrain. After detonating four to six mines, the MCR is no longer serviceable. One study found that both of 1st Marine Division’s attempts to proof lanes with the MCR were unsuccessful during Operation Desert Storm.44 Just like the MCB, operators must train with the MCR to develop proficiency.

Equipment limitations pose a significant problem for the ABCT to reduce the density and depth of obstacles as seen in Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Once the AFU successfully breached, the RAF deployed “mines with artillery, ISDM Zemledeliye mine-laying systems, and even drones, such as the POM-3 and PFM-1 antipersonnel mines….[which] are used to refill lanes cleared by Ukrainian sappers and to mine roads behind Ukraine’s front lines.”45 An RAF obstacle platoon consisting of three GMZ-3 mining vehicles can lay a 1,200 meter three-row minefield of 624 mines in 26 minutes.46 Thus, units may need to reduce and proof lanes multiple times. The key issues with tank-mounted mine clearing equipment are that it restricts mobility and firepower, has limited endurance, and lacks mass. Although the US Marine Corps faced the same constraints with mobility, firepower, and endurance in Operation Desert Storm, a number of M1 Abrams tanks towed a Mk 58 trailer containing a single MICLIC.47 Similarly, the Ukrainian experience demonstrates the need to build additional mass and capability with explosive and mechanical mine reduction equipment to enable combined arms breaching.

According to one think tank, after the initial failed breach attempts, the AFU transitioned to small-unit dismounted assaults “to maintain a high tempo of ground attacks and attrite Russian forces in the process to achieve an operational breakthrough.”48 Still, the AFU failed to generate sufficient tempo to penetrate RAF defenses. Even during the AFU’s successful breach at Rivnopil, however, the RAF retrograded to subsequent positions, and AFU advances remained 700m to 1200m each week. The AFU were unable to successfully breakthrough in part because the assault force did not transition to execute a follow-on breach quickly enough to keep the RAF off-balance. Thus, to maintain initiative and tempo when penetrating multiple obstacle belts, sustained breaching may require a unit to rapidly transition from the assault force to the support force.

The Ukrainian experience shows that SOSRA remains an essential framework to plan and execute the combined arms breach. Indeed, AFU failures can be traced back to violating a breaching fundamental. The evolving operational environment, however, creates multiple challenges for the ABCT to apply SOSRA to breaching operations. Although finding solutions to current tactical or technical shortfalls is valuable, it is more important for leaders to apply a maneuverist mindset to combined arms breaching by exploiting enemy vulnerabilities and placing them in a combined arms dilemma.

Synchronization: The Key to Combined Arms

ATP 3-90.4 Combined Arms Mobility describes the importance of synchronization as a breaching tenet within the context of the support, breach, and assault forces. Synchronization, which is achieved through detailed reverse planning, clear sub-unit instructions, effective command and control, and combined arms rehearsals, ensures actions occur at the appropriate time.49 Synchronization should not be reduced to the timing of suppression and obscuration, however; it must also relate to the effects of these actions on the enemy. As discussed above, the two breaches near Novodarivka at the beginning of the counter-offensive failed largely due to the lack of a direct fire support force and no obscuration. Still, despite synchronizing breach force direct fires with indirect fires, the 47th Mechanized Brigade was unable to prevent the RAF from destroying the breach force.

Therefore, rather than narrowly applying synchronization to direct and indirect fires, leaders must consider the synchronization of all friendly warfighting functions (WfFs), consisting of command and control, movement and maneuver, fires, intelligence, sustainment, and protection, as well as the desynchronizing of enemy WfFs.50 Intelligence is its own breaching tenet, but degrading the enemy’s intelligence capability serves an equally important role. As another example, sustainment has a critical role in ensuring resources are available to the support, breach, and assault forces during all phases of the operation. Additionally, vehicle recovery plans are critical to prevent breach lanes from being blocked by immobilized vehicles. Shaping operations near Rivnopil which targeted RAF sustainment had both physical and moral effects on the defending company, and enabled 31st Mechanized Brigade’s assault. Thus, commanders and staffs must look beyond synchronizing friendly action and aggressively tear apart the enemy’s system.

The Problem of Mass

From July through November 2023, the primary method to reduce obstacles was with dismounted sappers operating as small teams during twilight. Since the AFU used armored vehicles mainly in defensive roles to retain terrain, the RAF began to employ loitering munitions on a larger scale. “At first, our problem was mines. Now, it’s FPV [first person viewer] drones,” said a 47th Mechanized Brigade platoon leader.51 Although the AFU had ceased conducting mechanized combined arms breaches, the operational environment presented an enduring challenge of how to mass breaching assets while being constantly sensed and targeted.

The core issue for the ABCT is having the minimum force of explosive and mechanical breaching assets required to reduce obstacles in depth while being targeted. The limitations of MICLICs, MCBs, and MCRs necessitates them being used together. Currently, the ABCT has a limited number of this mine-clearing equipment which supports a limited number of lanes and can easily be targeted by UAS. Although there are intriguing technologies to enable force protection, such as vehicle-mounted UAS jammers and anti-thermal paint, it is more important for units to control their physical and electromagnetic signature. As the AFU experience at Novodarivka showed, the breach force must mass sufficient mine-clearing assets for the length of the reduction area or it will be destroyed in the breach.

Conclusion

The 2023 Ukrainian counter-offensive demonstrates that a critical capability to enable maneuver remains the combined arms breach. The ABCT will fight within a different operational context. Nevertheless, the AFU’s experience suggests that to successfully breach in large scale combat operations (LSCO), the ABCT must 1) build capability and competency to conduct detailed reconnaissance for the entire depth of the breach area; 2) appropriately weight the support, breach, and assault forces; 3) emphasize shaping operations to enable the breaching fundamentals as well as increase the capacity to reduce obstacles in depth; 4) seek ways to synchronize all friendly warfighting functions and desynchronize the enemy’s; and 5) increase both mechanical and explosive breaching assets to prevent a mismatch between obstacle depth and equipment.

Two hundred years ago, Carl von Clausewitz asserted that although the defense is the stronger form of war, the offense is the most decisive.52 The “maneuver warfare is dead” debate distorts this assertion and overlooks the role of the combined arms breach, which remains as important as it is difficult. Today, the ABCT must monitor trends in current conflicts, think critically about how it will execute breaching operations, and strenuously train with the tools it currently has to successfully maneuver.

Captain Austin Bajc currently serves as the Company Commander of Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 37th Armor Regiment, 2nd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Division, Fort Bliss, Texas, following previous command of A Company, 1st Battalion, 37th Armor Regiment, and assignments as the Heavy Weapons Troop Executive Officer for Q Troop, 4th Cavalry Regiment, and Scout Platoon Leader for O Troop, 4th Cavalry Regiment, both in Rose Barracks, Germany. Captain Bajc’s military education includes the Armor Basic Officer Leaders Course, Army Reconnaissance Course, Cavalry Leader's Course at Fort Benning, Georgia, and the USMC Expeditionary Warfare School in Quantico, Virginia, and he holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in History from Virginia Military Institute.

Notes

1Seth G. Jones, Alexander Palmer, and Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “Ukraine’s Offensive Operations: Shifting the Offense-Defense Balance,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 9 June 2023, 13.

2David Axe, “On One Key Eastern Battlefield, The Russians Are Losing 14 Vehicles For Every One The Ukrainians Lose,” Forbes, 14 November 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidaxe/2023/11/14/on-one-key-eastern-battlefield-the-russians-are-losing-14-vehicles-for-every-one-the-ukrainians-lose/?sh=2c3351115838

3Randy Noorman, “The Return of the Tactical Crisis,” Modern War Institute, 27 March 2024, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/the-return-of-the-tactical-crisis/

4Seth G. Jones, Alexander Palmer, and Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “Ukraine’s Offensive Operations: Shifting the Offense-Defense Balance,” 4.

5Daniele Palumbo and Erwan Rivault, “Ukraine war: Satellite images reveal Russian defences before major assault,” BBC News, 21 May 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-65615184

6Seth G. Jones, Alexander Palmer, and Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “Ukraine’s Offensive Operations: Shifting the Offense-Defense Balance,” 8; Gerry Doyle, Vijdan Mohammad Kawoosa and Adolfo Arranz, “Digging in: How Russia has heavily fortified swathes of Ukraine,” Reuters, 27 April 2023, https://www.reuters.com/graphics/UKRAINECRISIS/COUNTEROFFENSIVE/mopakddwbpa/

7Lester Grau and Charles Bartles, The Russian War of War: Force Structure, Tactics, and Modernization of the Russian Ground Forces, (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Foreign Military Studies Office, 2016), 305.

8“In Ukraine, a war of incremental gains as counteroffensive stalls,” The Washington Post, 4 December 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/12/04/ukraine-counteroffensive-stalled-russia-war-defenses/

9Dr Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, 8.

10“In Ukraine, a war of incremental gains as counteroffensive stalls,” The Washington Post.

11ATP 3-90.4, Combined Arms Mobility, 3-7.

12Mingus Pozar, Tony Huggar, and Matteo Muehlhauser, “Russian Large Scale Combat Operations (LSCO) in Ukraine,” Emergent Threat, Training, and Readiness Capability, 24 August 2023, 5-8.

13ATP 3-90.4, Combined Arms Mobility, 3-10.

14ATP 3-90.1, Armored and Mechanized Infantry Team, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, October 2023), C-7.

15Ibid.

16Ibid.

17ATP 3-90.4, Combined Arms Mobility, 3-18.

18Dr Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, 5; “In Ukraine, a war of incremental gains as counteroffensive stalls,” The Washington Post.

19Dr Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, 9.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23Ibid, 12.

24 “In Ukraine, a war of incremental gains as counteroffensive stalls,” The Washington Post.

25 “Frontline report: Ukraine takes tactical heights in Rivnopil with minimal engagement,” Euromaiden Press, 27 June 2023, https://euromaidanpress.com/2023/06/27/frontline-report-ukraine-takes-tactical-heights-in-rivnopil-with-minimal-engagement/

26 Dr Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, 13.

27 “Frontline report: Ukraine takes tactical heights in Rivnopil with minimal engagement,” Euromaiden Press.

28 Recommendations For Combat Against The Enemy Operating In Tank And Mechanized Columns, (Rostov-on-Don, 2023), 48.

29 Ibid, 48.

30 Recommendations For Combat Against The Enemy Operating In Tank And Mechanized Columns, 35; Dr Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, 19.

31 Recommendations For Combat Against The Enemy Operating In Tank And Mechanized Columns, 27.

32Recommendations For Combat Against The Enemy Operating In Tank And Mechanized Columns, 14; Dr Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, 18.

33 “In Ukraine, a war of incremental gains as counteroffensive stalls,” The Washington Post.

34David Ignatius, “Ukraine’s counteroffensive ran into a new reality of war,” The Washington Post, 7 December 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/12/07/ukraine-counteroffensive-russia-war-drones-stalemate/

35Stephen Biddle, Military Power: Explaining Victory and Defeat in Modern Battle, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004), 5.

36ATP 3-90.4, Combined Arms Mobility, 3-8.

37Dr Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, 13.

38ATP 3-90.4, Combined Arms Mobility, 3-8.

39Dr Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, 22.

40Michael Kofman and Rob Lee, “Perseverance And Adaptation: Ukraine’s Counteroffensive At Three Months,” War on the Rocks, 4 September 2023, https://Warontherocks.Com/2023/09/Perseverance-And-Adaptation-Ukraines-Counteroffensive-At-Three-Months/

41ATP 3-90.4, Combined Arms Mobility, B-6 to B-9.

42Thomas Houlahan, “Mine Field Breaching in Desert Storm,” Journal of Mine Action: Vol. 5 Iss. 3 (2001), 27-29.

43ATP 3-90.4, Combined Arms Mobility, B-17 to B-19.

44ATP 3-90.1, Armor and Mechanized Infantry Company Team, C-21.

45Thomas Houlahan, 28.

46Michael Kofman and Rob Lee.

47Lester Grau and Charles Bartles, 305.

48Thomas Houlahan, 29.

49Konrad Muzyka, Konrad Skorupa, and Ireneusz Kulesza, “Rochan’s report: Ukraine counteroffensive Initial assessment (June-August 2023),” Rochan Consulting, September 2023, 56.

50ATP 3-90.4, Combined Arms Mobility, 3-11.

51FM 3-0, Operations, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1 October 2022), 2-1.

52Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 358.

Social Sharing