Baselining

This article is designed to serve as a guide to assist junior officers in understanding their role within the overall convergence framework in either a battalion/brigade staff position or within their key developmental platoon leader or company commander role. It is in no way a comprehensive analysis of convergence and multidomain operations, nor a prescriptive approach of how to plan and conduct operations. The primary audience for this article is the future platoon leaders and company commanders currently or shortly entering their respective professional military education course.

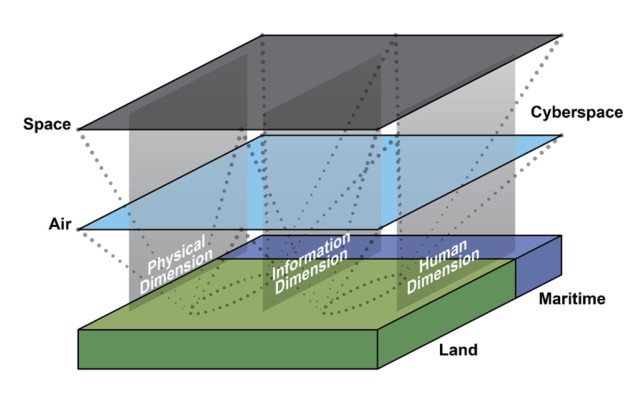

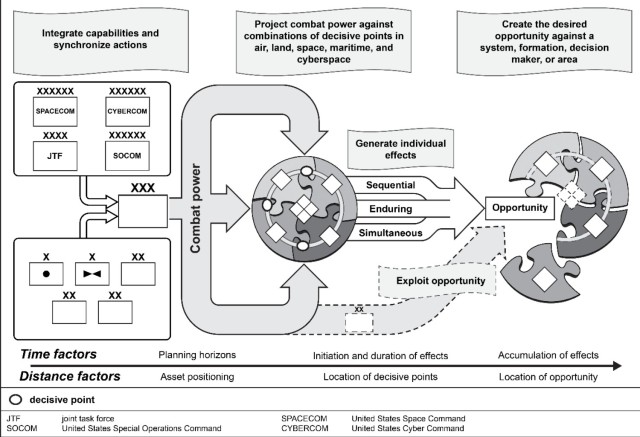

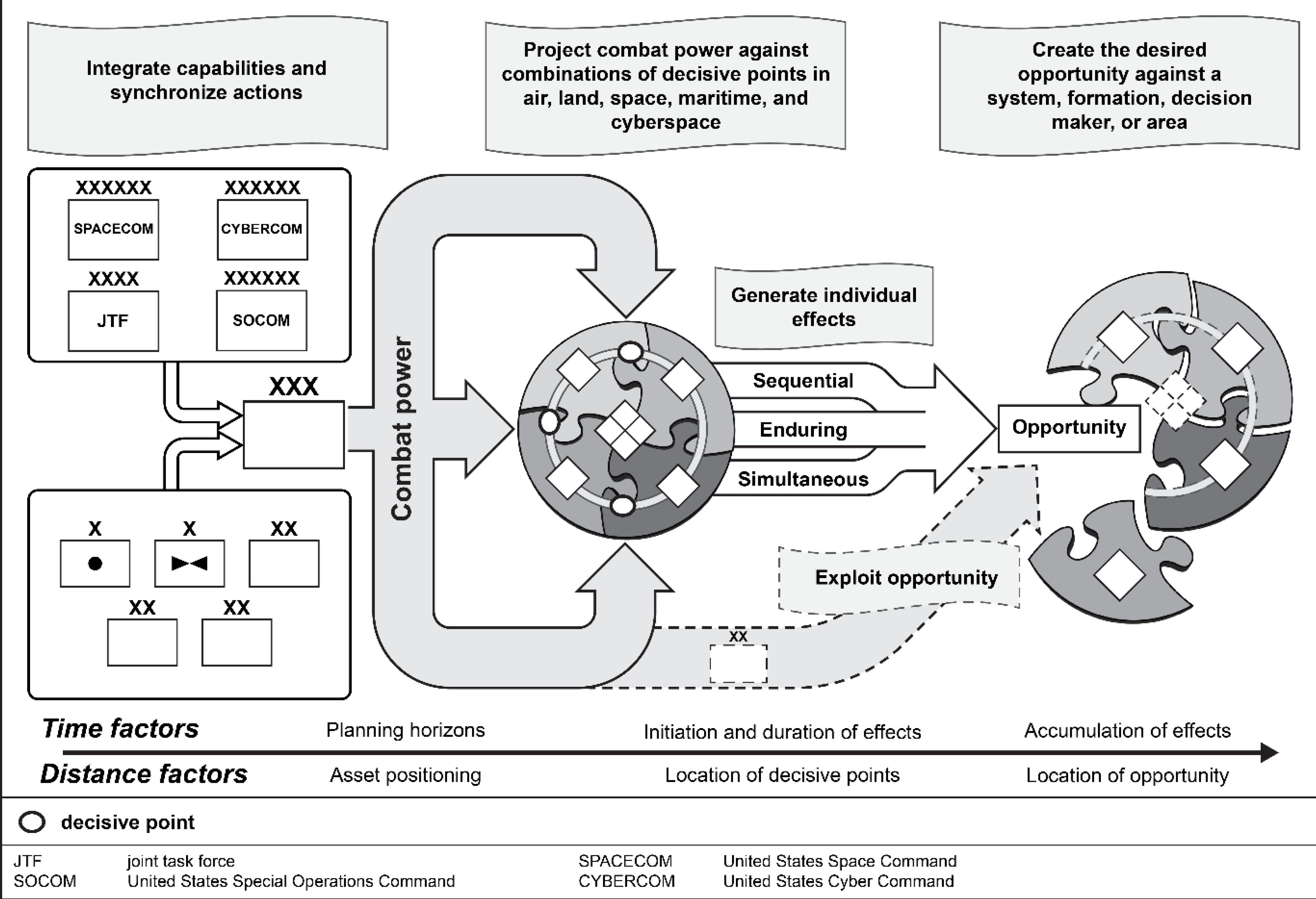

It is important to first know the doctrinal definitions for the following terms used throughout this article. A domain is defined as “a physically defined portion of an operational environment requiring a unique set of warfighting capabilities and skills.”1 Multidomain operations (MDO) are “the combined arms employment of all joint and Army capabilities to create and exploit relative advantages that achieve objectives, defeat enemy forces, and consolidate gains on behalf of joint force commanders.”2 Convergence is “an outcome created by the concerted employment of capabilities against combinations of decisive points in any domain to create effects against a system, formation, decision maker, or in a specific geographic area.”3

True to doctrinal form, these definitions encompass many ideas in a lot of words and can be difficult to understand upon their initial read. However, in more general terms convergence is the combination and synchronization of multidomain effects enacted on an adversary that aids in achieving overall mission success.

As junior officers, with respect to mission planning, we are taught largely through the lens of achieving decisive points in order to accomplish the mission. Platoons’ decisive points, however, are very often different from the company decisive point; and it’s on the officer at echelon to ensure they understand what their respective decisive point is and how it supports the overall mission of their higher echelon.

This discrimination of decisive points chiefly falls under the concept of main and supporting efforts. The main effort “is a designated subordinate unit whose mission at a given point in time is most critical to overall mission success.”4 A supporting effort is a subordinate unit “with a mission that supports the success of the main effort.”5 This is a counterintuitive statement, but the supporting efforts are the most important units in an operation. To use a sports analogy, this is akin to a quarterback throwing a touchdown to the receiver (the main effort) from 40 yards out. It takes the receiver time to get down the field, and the quarterback needs time to scan targets, make the mental calculations for the throw, and throw an accurate pass. The time they are given is the most important part, and that is given by the offensive line (a supporting effort). Without the supporting effort(s), the main effort would fail. This is where convergence and MDO come into play.

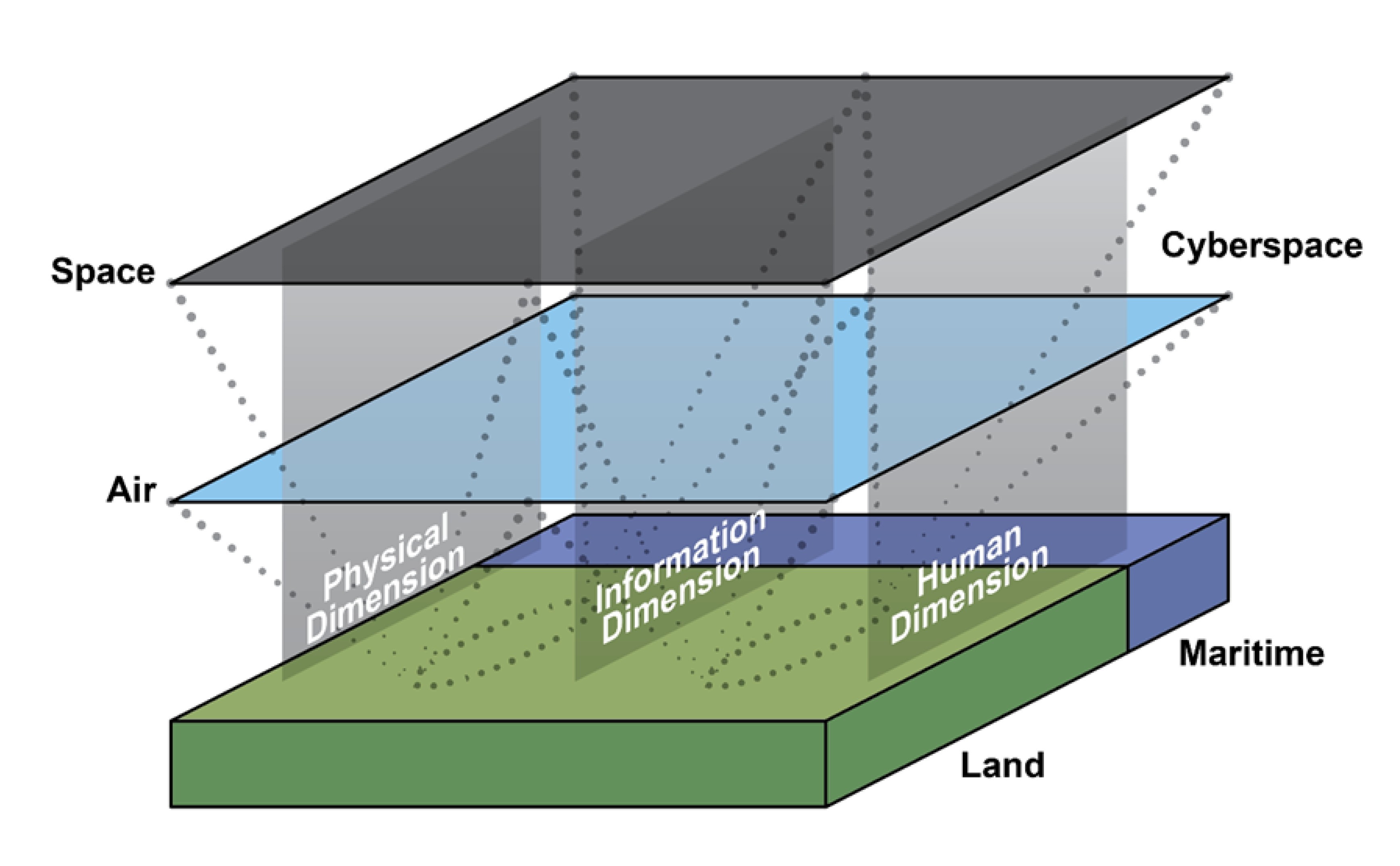

As defined in Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations, there are five domains: maritime, land, air, space, and cyberspace.6 As a junior officer, a general understanding of how the forces within those domains interact with the sum of its parts is important to understanding convergence and, subsequently, how convergence can lead to decisive points.

Each domain has myriad assets that can operate within it. Sea assets can be a single submarine or entire battle carrier group, while land assets can be a combined arms battalion or an entire infantry airborne brigade conducting a vertical envelopment. Air assets include fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft or assets echelons above brigade like the recently retired Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System (JSTARS). Space assets are varied and greatly influence all other domains as things like global positioning systems, target acquisition, and electromagnetic warfare originate there. Finally, cyberspace includes critical assets like the Internet of Things (IoT), the electromagnetic spectrum, and computer systems and processes.

At the conclusion of this article, I hope to provide greater clarity of the convergence window of opportunities to those junior officers who are ultimately the implementors of staff plans as the Army, rightfully, places greater emphasis on convergence.

The Why

For two decades the Army engaged almost completely in counterinsurgency (COIN) operations in the Middle East and Central Asia. U.S. presidents, dating back to former President Obama, though, aimed at pivoting the United States and Department of Defense (DoD) towards the Indo-Pacific Command area of responsibility to ready itself and keep pace with the growing Chinese presence in the region.7 At the conclusion of the war in Afghanistan in 2021, the Army affirmed its need to transition from a COIN mentality to one of large-scale combat operations (LSCO), which are “extensive joint combat operations in terms of scope and size of forces committed, conducted as a campaign aimed at achieving operations and strategic objectives.”8 LSCO in its most basic form is peer-to-peer, or near-peer to peer, warfare — a type of war the United States did not have to fight during its global war on terrorism days. An innate aspect of LSCO, from an economic perspective, is that we live in a resource-constrained environment. The days of the U.S. having simultaneous and continuous overmatch capability in air, space, and sea domains, and being able to provide assets consistently with minimal consequence, are largely gone.

During LSCO, assets must be assigned and protected by their supporting unit, or they risk destruction. Additionally, the amount of assets available by domain is subject to exogenous factors like crew rest, maintenance, flight hours, or enemy anti-access/area denial. With economy of force in mind, convergence then becomes paramount to mission success because it means that commanders and their planners have a finite amount of time and resources to execute the commander’s vision.

For junior officers, this means that their platoons and companies must be ready at a moment’s notice to execute a plan that may be only “good enough.” Platoon and company-level leaders must conduct parallel planning with their higher staff to determine what their decisive points may be; likewise, battalion and brigade staffs must inform their subordinate units of their planning efforts and keep them abreast of what assets are available and at what times.

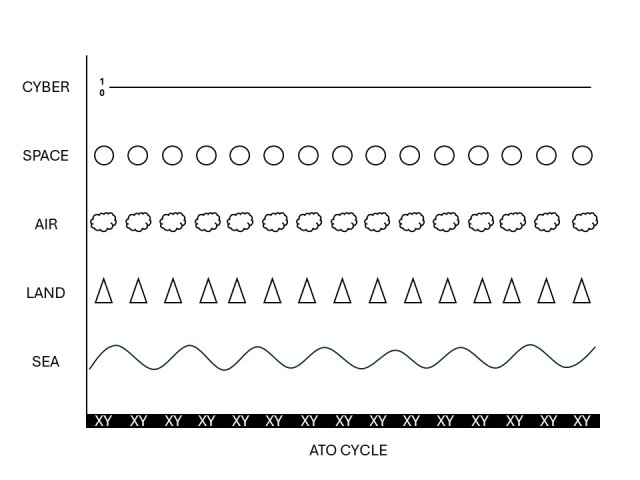

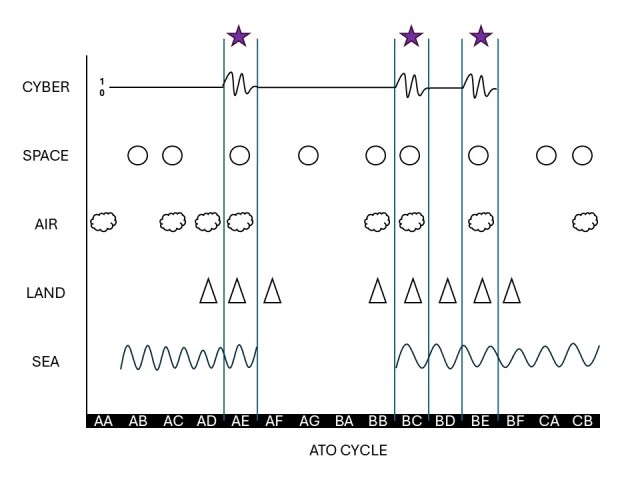

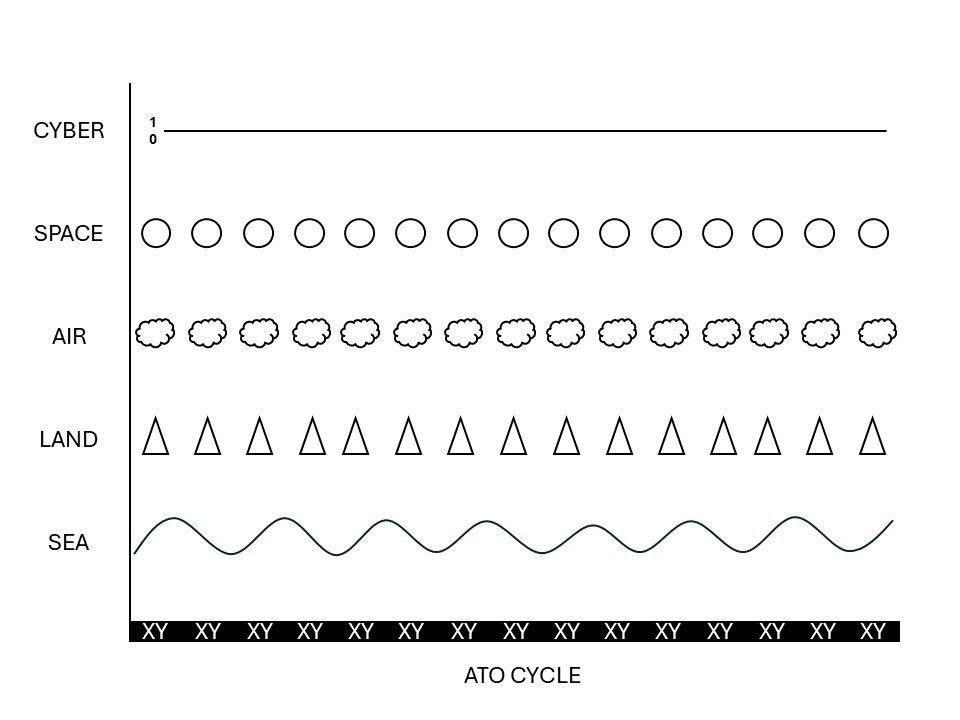

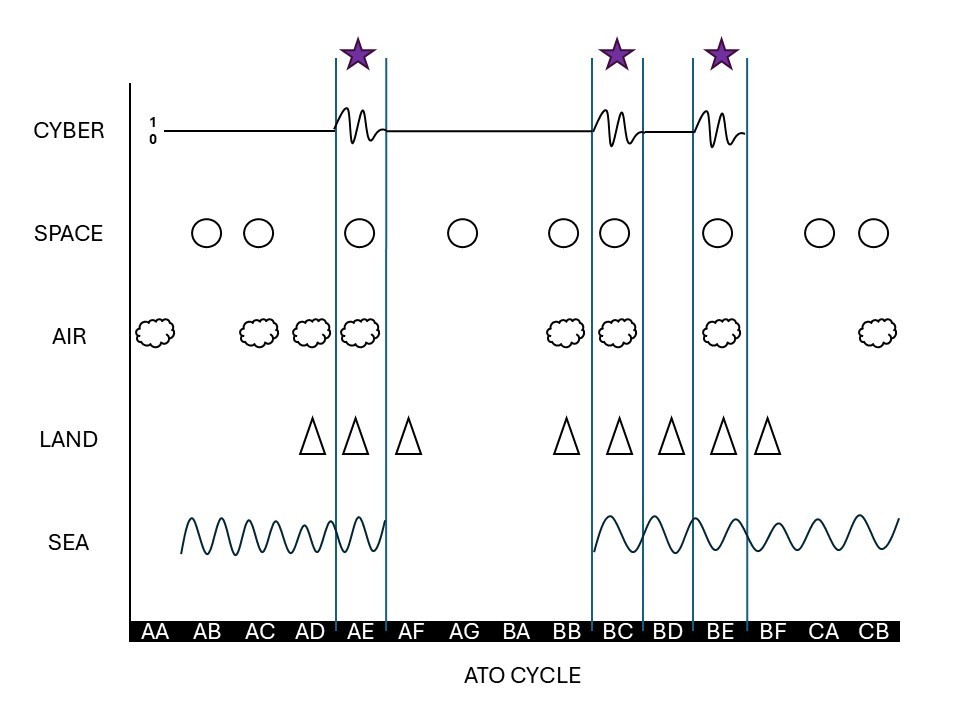

FM 3-0 illustrates how the operational environment generally applies to the battlefield (Figure 1) as well as demonstrates a convergence outcome example (Figure 2).9 However, there is not a combined diagram to show both, nor one that is easily understandable. In this endeavor, I created a diagram (Figures 3 and 4) to help bridge this gap and more easily show the relationships between MDO, convergence, and decisive point planning.

In Figure 3, the diagram is broken down into an X axis with the air tasking order (ATO) cycle, and the Y axis with the five domains. Essentially, the ATO cycle is the governing document on which assets are available at which times and for how long. Within the area of the X and Y axis are icons denoting non-specific assets within each domain and their application in that ATO. In a perfect world, this would mean all resources are available at all times; as previously stated though, we operate in a resource-constrained environment, so this is impossible. Figure 4, therefore, attempts to show how convergence can be applied in a realistic, albeit simplified, way that highlights planning and preparation of the battlefield, execution of the decisive point, and the follow-through of an operation.

Implementation

For example, let’s say an Army corps is conducting operations in preparation for an attack across the international boundary of a fellow NATO state that has been attacked by its aggressive neighbor and seized multiple provinces of its territory. Both the NATO state and the aggressor state are considered peers militarily to the United States. Using Figure 4, we can assume that the ATO cycles prior to the first purple star (a decisive point) are spent in planning and preparation: The Navy is positioning an aircraft carrier; Army forces are receiving equipment from the port or preposition stock; Air Force bombers are planning routes stateside; the Space Force is providing insights on optimal time and range for satellites in near-Earth orbit and low Earth orbit; and Cyber Command personnel are preparing to disrupt portions of the electromagnetic spectrum within the affected provinces. But once ATO “AE” starts, domains align in their asset capability and implementation, and the corps commander orders a show of force with limited engagements for specific units. These units and their staffs have anticipated this convergence window and execute, achieving the first decisive point.

After this ATO window, those Army units consolidate gains and prepare for follow-on operations. As ATO “BC” approaches, units at echelon within domains are again planning and preparing, but this time when the convergence window opens, the corps commander orders a deception operation to make the adversary’s commander believe the U.S. will not attack where he’s expecting them to, thus achieving decisive point two. Using the momentum from the successful deception operation, the commander effectively pivots to his main effort (a brigade combat team [BCT] with the full weight of the other four domains’ assets behind them) in ATO “BE” to breach and destroy the enemy commander’s main force, achieving decisive point three and overall mission success.

There is significantly more nuance behind this basic narrative as well as time between operations and planning, but the idea remains the same: Convergence to achieve the decisive point equals mission success. In this example, the BCT is the quarterback/receiver combo with their task to conduct the breach, but without the supporting efforts of the limited objective units, the units conducting the deception operation and the assets available at echelon in each domain, the main effort will either fail or achieve a Pyrrhic victory.

As a junior officer in any military occupational specialty or branch of service, this means you as the leader of that echelon must know your task and purpose and know the bigger picture two levels up. Your organization must be poised to react when the order is given, as time and material resources are finite. Failure to achieve a decisive point within a specific convergence window may mean overall mission failure. For junior officers on a battalion and brigade staff, this means you must understand and produce meaningful products that convey convergence windows and attempt to anticipate and relay to subordinate units when those windows will occur to capitalize on a relative advantage.

Bringing It All Together

Convergence is perhaps the single most important concept of military doctrine today. The fundamentals behind convergence aim to bring about the most destructive means to bear on an enemy in the smallest amount of time with the least amount of resources. Convergence becomes even more important when considering historically that single operations or battles by and large do not lead to overall war winning.10 Attrition-based warfare is a consistent factor in wars; however, adherence to convergence windows allows for the magazine depth required for protracted conflicts.

Convergence window planning at the tactical level is imperative. This can be achieved through various mediums, but products like an execution checklist, intelligence collection synchronization matrix, and targeting synchronization matrix are crucial to tactical level commanders and leaders. These products are part of a minimum-level product packet that company commanders and platoon leaders must know and understand during any operation because these illustrate, in product format, convergence windows. These also provide invaluable information about potential MDO assets passing through a company’s or platoon’s area of operations during the operation. This allows greater cross-communication and reduces the risk of fratricide.

For junior officers, convergence is the formula for future military success and must be rigorously planned for and anticipated. Understanding and implementing this ideology at the junior level today will ensure success for the Army of the future.

Notes

1 Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations, October 2022.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Army Doctrine Publication 3-0, Operations, July 2019.

5 Ibid.

6 FM 3-0.

7 Oriana Skylar Mastro, “The Pivot That Wasn’t,” Foreign Affairs, 18 June 2024.

8 Ibid.

9 FM 3-0.

10 Cathal J. Nolan, The Allure of Battle: A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

CPT Tice Myers commands A Company (Experimentation Force), 1st Battalion, 29th Infantry Regiment at Fort Benning, GA. He received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in international relations from Virginia Tech and the American University, respectively. He has served as a platoon leader within the 82nd Airborne Division and commanded within the 3rd Infantry Division. He has completed two overseas tours, one combat to Afghanistan and one rotational to the European Command.

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue of Infantry. Read more articles from the professional bulletin of the U.S. Army Infantry at https://www.benning.army.mil/Infantry/Magazine/ or https://www.lineofdeparture.army.mil/Journals/Infantry/.

As with all Infantry articles, the views herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Defense or any element of it.

Social Sharing