The purpose of this article is to share an approach to using the platoon live-fire exercise (LFX) as a training event to build equal capacity across all rifle platoons. We reframed the training as “installing a play” rather than a test, with the goal of preparing all nine rifle platoons to execute a platoon attack under any conditions. This framework relies on two critical components: transparency and measurement. I outline how clear, consistent communication of expectations and timely introduction of performance measures led to a novel and effective training experience for all participants.

Transparency: A Foundation for Focus

Focus is a superpower. This adage guided our battalion’s approach to achieving high levels of training proficiency across mission-essential task lists (METLs). For an airborne infantry battalion, it’s vital to prioritize high-payoff tasks that account for roughly 80 percent of training requirements. Guided by mentors, we emphasized focusing leaders’ time and energy on such tasks. For our battalion, these were defined by echelon:

• Fire Team: React to contact, break contact, single team/single room.

• Rifle Squad: React to contact, break contact, mechanical reduction of a simple obstacle, establish a foothold, knock out a bunker, multi-team/multi-room.

• Rifle Platoon: Platoon attack, establish and fight a support by fire (SBF), reduce and assault (suppress, obscure, secure, reduce and assault — SOSRA), integrate direct and indirect fires.

Upon assuming command in November 2023, we consistently emphasized these priorities in leader professional development sessions, written training guidance, and leader engagement opportunities. By July 2024, we published a warning order for the platoon LFX to focus platoons and staff on preparation and resource acquisition. The exercise was executed in November 2024, using a training area tailored to meet our objectives.

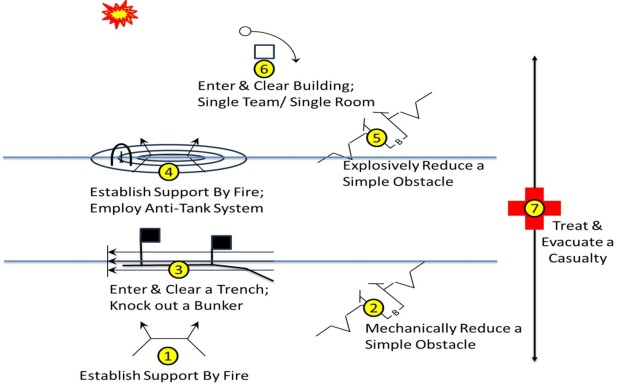

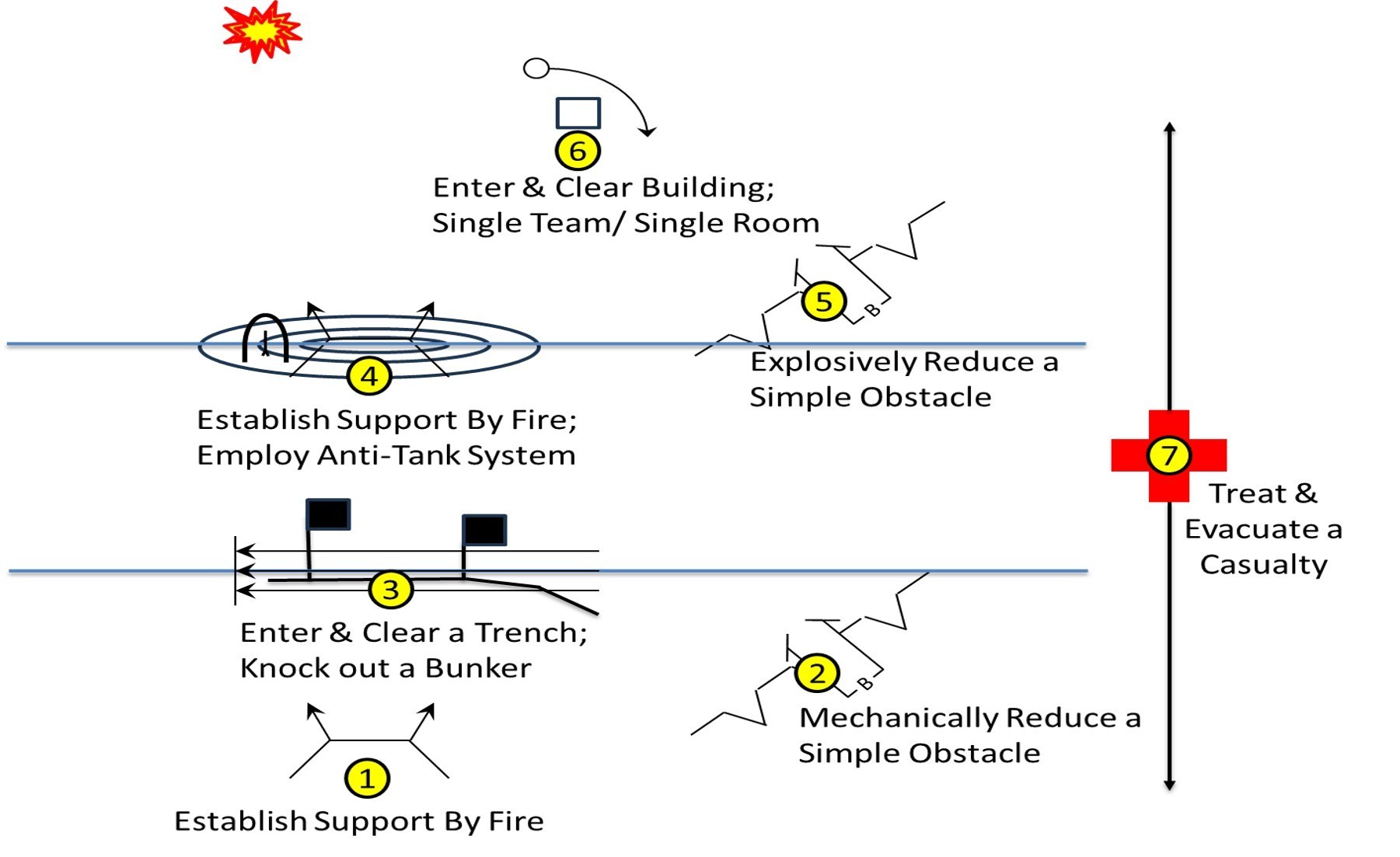

Our platoon LFX prioritized skills unique to live-fire conditions over tasks suited to situational or field training exercises (see Figure 1). Transparency in our case simply meant ensuring all Soldiers clearly understood the standards and expectations, as well as how we would measure each task, before the training was executed. Due to the Hawthorne Effect, we anticipated the platoons would adjust to the measures, but we accepted this knowing the results would be shared to encourage learning from others’ performance, without the intent to rank or compare.1 This approach resulted in a denser array of tactical tasks across a shorter distance, including seven key platoon-level events highlighted in Figure 1.

We approached the training utilizing the Eight-Step Training Model with a novel modification of Step 2: Train and Certify Leaders.2 Reframing the “train” portion of Step 2 as “installing a play” effectively aligned expectations, ensuring that all nine rifle platoons executed their platoon attack the same way under any conditions. In sports, the installation of a play is when a coach draws a graphic of where and how he or she wants each position to act. We “drew up our play” during the two touchpoints discussed below to establish a clear precise directive for our platoon attack, akin to hand placement and body placement in a sports play:

1. Platoon Leader and Platoon Sergeant Briefing: A week prior, we outlined our seven tactical problems and discussed how we wanted the leadership to execute their maneuvers. During this dialogue we introduced novel metrics for evaluation for each of the tactical problems. This encouraged proactive thinking and discussion.

2. Tactical Exercise Without Troops (TEWT): The day before execution and guided by the battalion command team, team leaders, squad leaders, and platoon and company leadership walked through the training area to discuss each tactical problem including the constraints of their weapon systems and measurement criteria. This hands-on approach ensured clarity and fostered ownership.

Most platoon LFXs are certification events and carry the psychological burden of a test; under the “installing a play,” we aimed for the training to produce units capable of executing the platoon attack, specifically at night. Our choice not to treat this as a test wasn’t to avoid failure, which is a great teacher, but to ensure all Soldiers put forth their best efforts without fear of job security (which is notoriously attached to these events).3

Measurement: Driving Behavior and Improvement

Drawing inspiration from CSM T.J. Holland’s insights on lethality metrics, “traditional metrics, while useful, fall short of capturing the full spectrum of lethality,” we developed additional measures beyond standard training and evaluation outlines (TO&Es).4 These metrics aimed to facilitate focused after action reviews (AARs) and productive discussions. Examples include (and are shown in Figure 1):

• Establishing SBFs 1 & 2: Time to set (minutes), shift and lift timings (minutes), target hits (count of hits), open-bolt stoppages (count of the number stoppages per open-bolt weapon system). For second SBF, we also measured the anti-tank (AT) high explosive (HE) hits (pass/fail).

• Conducting a Mechanical Breach: Suppress (pass/fail), obscure (pass/fail), secure (pass/fail); reduce (time from assault squad moving to establish far-side security, minutes), assault (pass/fail).

• Clearing a Trench/Bunker: Time from entering trench to second bunker clearance (minutes), target hits (count of hits).

• Conducting an Explosive Breach: Suppress (pass/fail), obscure (pass/fail), secure (pass/fail); reduce (time from assault squad moving to establish far-side security, minutes), assault (pass/fail).

• Clearing a Building: Assault-to-stack and stack-to-clear timings (minutes), target hits (count of hits).

• Performing Casualty Treatment/Evacuation: Self/buddy aid (pass/fail), time from point of injury to a 9-line (minutes), handover quality (subjective evaluation by the battalion medical platoon sergeant and readability of the Tactical Combat Casualty Care [TCCC]/Mechanism of Injury, Injuries, Signs and Symptoms, and Treatments [MIST] card).

Developing and sharing these measures of performance prior to execution guided onsite AARs, enabling quick identification of strengths and areas for improvement. During the onsite discussions we used a whiteboard with a sketch similar to Figure 1. The common understanding enabled a much quicker and focused onsite AAR discussion, enabling more time for platoons to retrain.

We displayed the culmination of our measurement efforts on a series of Powerpoint charts that captured data averages by problem set.5 These products were used to facilitate a second consolidated AAR one month later with all platoon leadership. This AAR facilitated a deeper discussion and allowed distribution of battalion-wide and platoon-specific performance data — each platoon received a product that had their data compared to the battalion averages.

Results, Reflections on Novelty, and Outcomes

The transparency and consistent messaging yielded significant benefits, resulting in all nine rifle platoons exceeding certification standards. Platoons arrived at the event prepared, allowing us to focus on challenges unique to live-fire conditions, such as integrating direct and indirect fires, managing violence during transitions, and executing SOSRA with a deeper understanding. Our “installing a play” approach mitigated test anxiety and mirrored sports team preparation — from whiteboard sessions to walk-throughs before execution on game day.

Our training scenario of seven tactical problems compelled each rifle platoon to require three rifle squads, a weapons squad, and a sapper squad. To achieve this, we were required to cross-train squads with multiple platoons within each company. By sharing the measurements of performance early and often with subordinate leaders, we standardized where leaders needed to focus their rehearsals and inspections, leading to a deeper understanding prior to execution. These additional “sets and reps” enhanced capacity and trust across the battalion.

The results from our measurements fostered meaningful discussions during AARs, with an emphasis on speed, aggression, and tactical transitions. Revisiting the training a month later with platoon leadership revealed insights on managing transitions, such as the importance of balancing speed with deliberate actions for greater advantage. One platoon sergeant’s observation on the psychological impact of indirect fire highlighted the value of linking onsite and post-training AAR lessons.6

Conclusion

This article is meant to offer a framework for others to consider when training their units. From a commander’s perspective, my biggest takeaways are:

1. Find what your team needs and focus on them via overcommunication. Overcommunication is a form of transparency. We overcommunicated our expectations to the team, at echelon, focusing on aspects of the attack (explained earlier), enabling subordinate leaders to build capacity anytime at echelon.

2. Once you have shared your expectations, use them regularly. Consistency is a form of transparency. We used our expectations to design and certify our platoons. Additionally, once we identified our measures of performance, we used them consistently to enable our training outcomes.

3. Seek new ways to evaluate performance and effectiveness but share them with your subordinates. Measurement is more art than science. Enabled by CSM Holland’s quest to seek unique ways to understand lethality and refine the assessment of our unit’s readiness, we sought novel measures of performance that would drive desired behaviors in our platoons.

4. Installing a play as a framework for training and certifying leaders led to a more productive training event. Removing the test anxiety by installing the attack proved effective for training nine equal platoons. Our battalion command sergeant major often states, “Practice doesn’t make perfect; practice makes permanent.” In the follow-up AAR, one of our platoon sergeants shared that during previous live fires, leadership was often stress-tested or overwhelmed. However, in our event, he noted that we stayed focused on our goal and, from his perspective, ensured all platoons improved their attack.

Our platoon LFX served as a seminal event to certify platoons and develop future company commanders and first sergeants. Through transparency and measurement, we built a training experience that not only prepared our platoons for combat but also provided a replicable framework for others. By consistently messaging priorities, engaging leaders, and leveraging metrics, we created a valuable model for building capacity across rifle platoons. This effort underscores the enduring principle: “Keep up the fire” as you look to train your teams and install your plays.

Notes

1 The Hawthorne Effect suggests that participants alter their behavior simply because they are aware they are being observed.

2 The U.S. Army’s Eight-Step Training Model – Step 1: Plan the training, Step 2: Train and certify leaders, Step 3: Conduct a reconnaissance, Step 4: Issue an order for the training, Step 5: Rehearse, Step 6: Execute, Step 7: Conduct an after action review, and Step 8: Retrain.

3 This was influenced by an article, “How Does Failure in Training Enable Learning?” by MAJ Kurt Wasilewski, which emphasizes the importance of failure as a critical component of effective training. Through the application of measured pressure and iterative, incremental progression, failure can be a tool for accelerated learning and improvement, demonstrating that the most valuable training experience often comes from enduring and overcoming “their hardest day.” The article can be read at https://fieldgradeleader.themilitaryleader.com/failure-wasilewski/.

4 CSM T.J. Holland, “Decoding Lethality: Measuring What Matters” Military Review Online Exclusive, October 2024, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/Online-Exclusive/2024-OLE/Decoding-Lethality/. This article discusses the U.S. Army’s efforts to refine the assessment of military readiness by integrating a comprehensive framework for evaluating lethality. It highlights the shortcomings of traditional metrics in capturing combat effectiveness and proposes new approaches, including Project Lethality, which incorporates factors such as holistic health and fitness, combat accuracy, and tactical proficiency to better measure and enhance a Soldier’s warfighting capabilities.

5 The format we used was the idea of our battalion forward support officer, who leveraged his experience from a previous fire support coordination exercise to capture and visually depict our actions over time.

6 The platoon sergeant mentioned that without real effects in front of an attacking platoon to demonstrate “setting conditions” the platoon tends to fall back on aspects of the attack they control — massing direct fire and speed of maneuver.

LTC Thomas (Tommy) R. Ryan Jr. currently commands the 2nd Battalion, 325th Airborne Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division, Fort Bragg, NC. His previous assignments include serving as an assistant professor of systems engineering at the U.S. Military Academy (USMA) at West Point, NY; planner for NATO Rapid Deployable Corps - Türkiye (NRDC-T); and staff officer for Joint Special Operations Command. He attended the Command and General Staff College – Red Team Member (University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies) at Fort Leavenworth, KS, and earned a bachelor’s degree from USMA and a master’s degree from the University of Arizona.

Author’s Note: This article would not have been possible without the tireless efforts of a superb staff that possessed the mindset and willingness to travel these winding roads with me.

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue of Infantry. Read more articles from the professional bulletin of the U.S. Army Infantry at https://www.benning.army.mil/Infantry/Magazine/ or https://www.lineofdeparture.army.mil/Journals/Infantry/.

As with all Infantry articles, the views herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Defense or any element of it.

Social Sharing