What Divisions owe Brigades in the Army of 2030

Download the full article here: No. 25-1014, Addressing Emerging Gaps in Rear Area Security: What Divisions owe Brigades in the Army of 2030 (May 25)

Background

Consistent trends at the Joint Multinational Readiness Center (JMRC) over the past five years reveal significant gaps and challenges with the brigade combat teams (BCT’s) ability to secure the rear area. ARSTRUC 25-29 changes eliminating the Brigade Engineer Battalion (BEB) from the BCT’s Modified Table of Organization and Equipment (MTO&E) and significant cuts to the Military Police (MP), who provide subject matter expertise in protection planning complicates the protection warfighting function for maneuver commanders. Subsequently, rotational training units (RTUs) at JMRC who lack U.S. MP enablers are increasingly reluctant to task U.S. maneuver units with security of the rear area. As a result, BCTs are increasingly demonstrating reliance on Multinational units to perform their rear area security and protection related tasks.

This concept imposes additional risk, because like U.S. BCTs allies and partners may not have organized, trained and equipped their forces to protect the rear area, and those partners may demonstrate additional command and control challenges. Furthermore, the allied or partner unit may lack technical expertise and sustainment architecture to effectively command and control their subordinate enablers. This lends itself to significant interoperability challenges with the lack of effective communication platforms and integration/synchronization of rear area activities with the applicable command node.

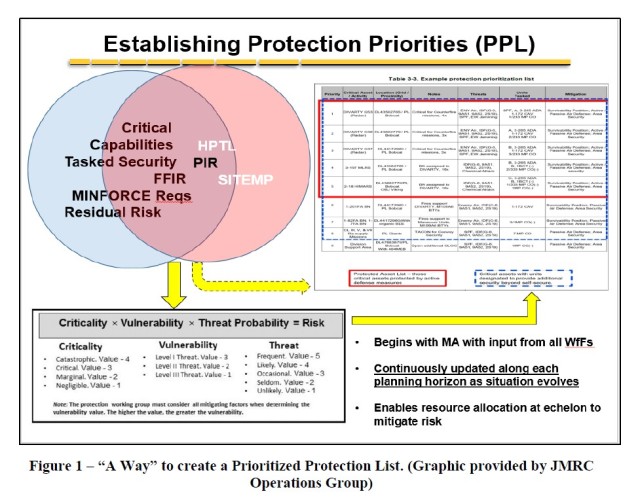

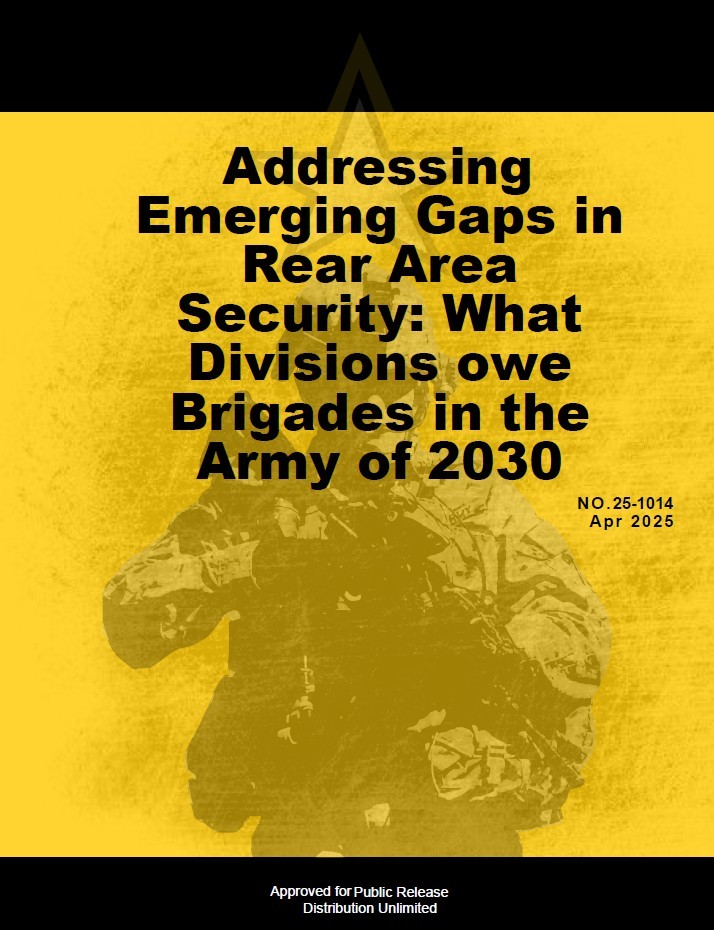

Recent trends show that RTUs are becoming less disciplined in coordinating protection efforts as a unified Warfighting Function (WfF). This trend inflates the RTU’s risk of overlooking their Protection WfF training objectives that impact the BCT’s overall readiness. Furthermore, RTUs are struggling to operationalize the assessment, identification, and mitigation of threats and hazards through a consolidated review of the Prioritized Protection List (PPL) and lack of a formalized Protection Working Group (PWG) in their battle rhythm. Concurrently, RTUs are increasingly limiting themselves with the inability to anticipate changes to protection prioritization during operational transitions. As a result, RTUs are increasingly unable to effectively organize protection assets to enable rear area security operations. Figure one depicts a “best practice” coached by JMRC Observer Controllers to create a PPL.

Context

Rear area security is one of the most critical tasks that BCTs overlook planning during LSCO. Doctrinally owned by the Protection WfF, the entire BCT staff should also prioritize these tasks to service this WfF to mass combat power and effectively manage risk for the commander.

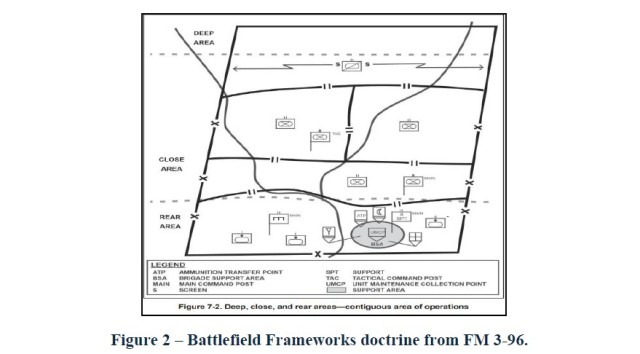

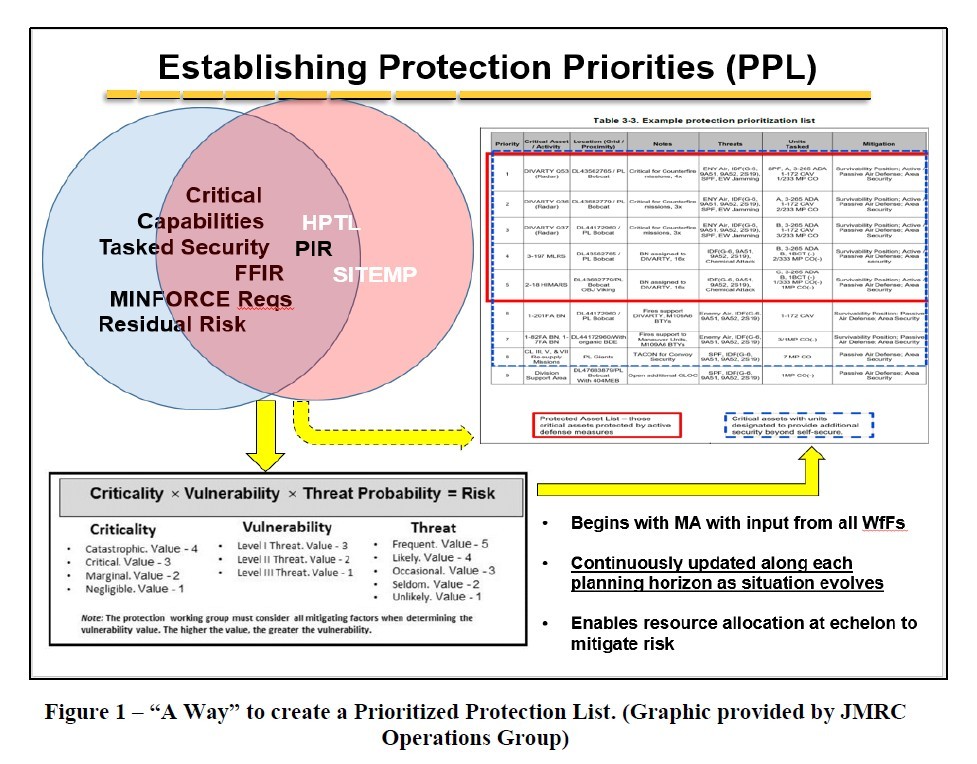

The operational framework defines the rear area as the area in a unit’s Area of Operation (AO) that extends forward from its rear boundary to the rear boundary of the next lower level of command. It is the area where most of the BCT’s forces and assets are located that support and sustain forces in the close area. Additionally, the rear area is the portion of the commander’s AO designated to facilitate the positioning, employment and protection of assets required to sustain, enable and support operations.

Activities/operations in the rear area primarily consist of security, sustainment, terrain management, movement control, protection, and infrastructure development. Critical and vulnerable nodes such as the BCT Main Command Post (MCP) and the Brigade Support Area (BSA) exist within the rear area and if degraded could have catastrophic effects on the BCT’s ability to conduct combat operations and accomplish the mission. Figure two shows a doctrinal template of how the battlefield frameworks delineate responsibilities.

Historically, the Army utilized combat support MP CO/PLT, as the formation of choice for conducting rear area security tasks to support the DIVs/BCTs. This in part is due to their robust mission profile combined with their massive firepower capabilities. However, with competing domestic mission requirements and ARSTRUC 25-29 changes that significantly reduced the MP Regiment’s force posture (~2,901 spaces cut), support to DIVs/BCTs will be increasingly limited and unpredictable for Army 2030. As a result, BCTs struggle to develop solutions with fewer security enablers to address the rear area problem set.

With the loss of the BEB in the ARSTRUC 25-29, BCTs must identify and task an organization to secure/control the rear area. BCTs often attempt to mirror the Division’s approach by establishing a Sustainment Command Post (SCP) to synchronize rear area security. However, this practice has proven ineffective, failing to improve coordination, cooperation, communication, and collaboration. Typically, BCTs assign a staff officer rather than a commander to lead the SCP, adding an unnecessary command node that reduces headquarters mobility and drains resources, ultimately decreasing overall combat power.

Observations

Current rotational trends at JMRC reveal that Brigades rarely prioritize planning security efforts for the rear area and dialogues with the Division HICOM in back briefs and confirmation briefs to find collaborative ways to mitigate this risk. A planning assumption commonly made because the DIV has the formations and resources in their inventory to defeat up to a level III threat. Concurrently, BCTs are cautious to allocate sufficient forces to secure the rear area because it diverts combat power away from the decisive action. Additionally, units often inadequately address battlespace management and security in the rear area during the planning process. Typically resulting in the brigade allocating insufficient combat power to the litany of tasks as the rear area aperture expands during different phases of the operation. BCTs tend to then mitigate Rear Area risk by assigning allies or partners to the rear portion of the battlefield framework, with the tactical task to secure. In recent rotations, assigning in this way has created command and control problems for the Brigade that were rare when brigades possessed BEBs.

In recent warfighters, DIVs and Corps appoint an MP BDE or MEB (Maneuver Enhancement Brigade) Commander to manage and synchronize rear area activities at their echelon. An approach that BCTs could adopt by appointing a Company or Battalion commander to own the terrain management and coordinate operations with all the elements in the rear area. This reinforces the requirement for a PWG with the identification of PPL requirements and assign units those assets accordingly. This approach further integrates the PPL requirements into all planning horizons and enables protection into plans and current operations.

Recommendations

Integration of multinational units on the battlefield and into the U.S. task organization is a common trend at JMRC and will undoubtedly prove essential to winning in LSCO. Tasking a multinational unit for responsibility to secure the rear area in hopes of preserving U.S. combat power for other mission represents a sub optimal value proposition. Commanders should carefully approach this as a U.S./multinational coordinated effort to balance capabilities and resources to meet the demands of the rear area’s security requirements. To accomplish this, commanders must gain an understanding of the multinational units’ capabilities and limitations to organize effectively and manage risk.

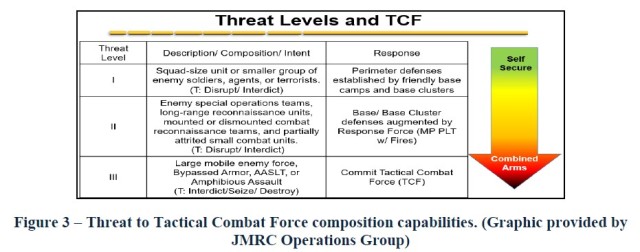

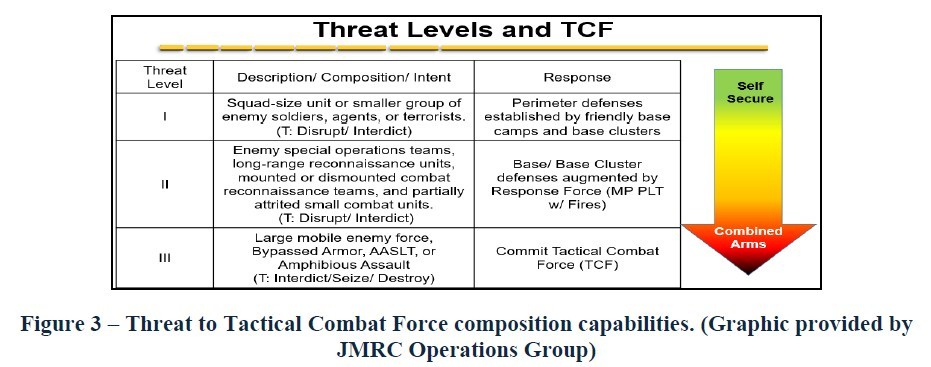

Equally as important, BCTs must ensure they are conducting detailed threat assessments during the planning process to balance rear area security considerations across space and time. Protection and Intelligence WfFs stakeholders must spearhead assessments aimed at synchronizing the rear area’s security requirements across all WfFs. These assessments must feed the integrating processes of intelligence preparation of the battlefield and targeting to better inform the correlation of forces mathematics that occur during course of action development. Simultaneously, the BDE S2 should provide the rear area threat as part of the Event Template to highlight for the commander/staff the critical events in that portion of the Battlefield Framework. Moreover, ADP 3-37 states the task organization of the unit assigned the area security mission should correspond with the level of threat. For example, if the threat in the rear area is a Level II threat (small-scale forces that can cause serious harm to military forces and civilians), an MP company should be sufficient. If the threat is a Level III threat (the capability of projecting combat power by air, land, or sea or anywhere into the area of operations), a combined arms team from a BCT is a more appropriate unit. DIVs regularly employ the Tactical Combat Force (TCF) to respond to level III threats within their AO but are generally not resourced below this echelon. A TCF is a rapidly deployable, air-ground, mobile combat unit with appropriate combat support and combat service support assets assigned to, and capable of defeating level III threats, including combined arms. If resources are available, BCTs should consider employment of a similar combat force to respond effectively to threats within their respective rear area. Figure three shows the combat correlation between threat and response that a unit must plan for in the rear area. As such, the correlation of forces informs the necessary preparation of a TCF in both the brigade and division rear areas. Dialogue and requests for forces to the division must follow if the brigade cannot source sufficient TCF for its rear area.

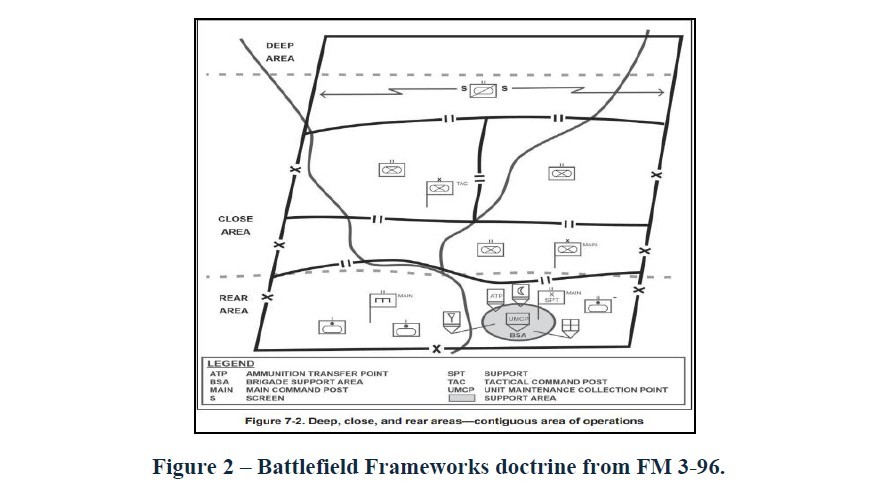

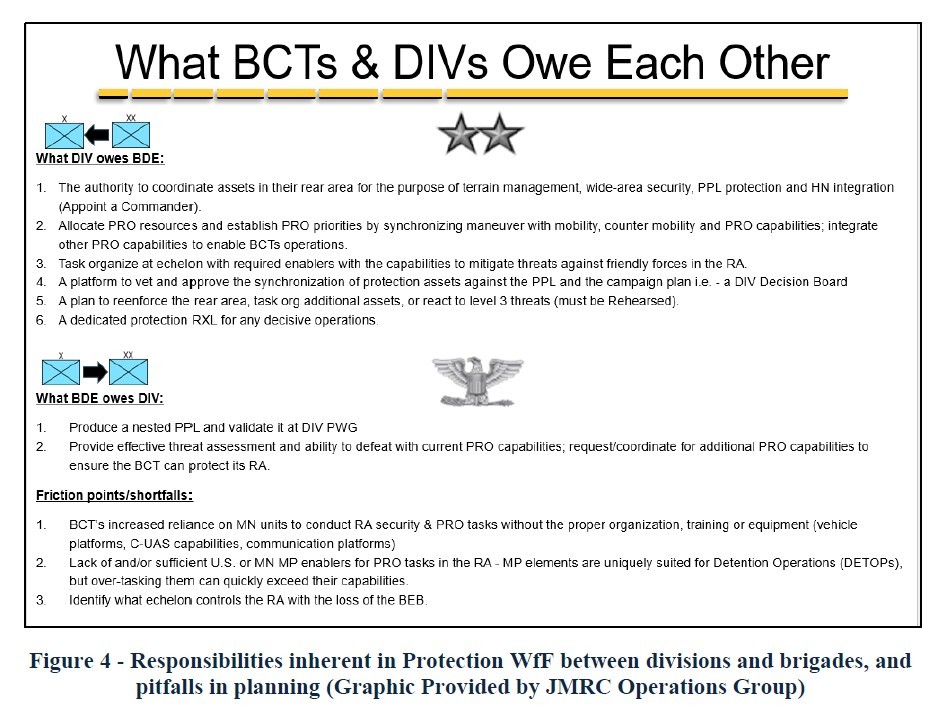

To enable the Brigade in Protection operations, the division must synchronize through rehearsals and resourcing of a TCF with an appropriate correlation of forces, acknowledging a lack of organic units with protection proponency. Planners and leaders often overlook Protection WfF during planning and fail to give priority or a voice during WfF specific rehearsals at the DIV/BDE level. For the Army of 2030, DIVs can further enable and resource BCTs with the adoption of a formalized Protection rehearsal hosted at the DIV level. This approach is a best practice that provides all Protection WfF stakeholders increased shared understanding with a consolidated plan to reinforce/synchronize all rear area operations and requirements. Figure four summarizes the best practices of responsibilities inherent in Protection WfF between divisions and brigades.

Conclusions

The rear area security problem set will continue to challenge BCT/DIV commanders in Army 2030. The removal of BEBs from the task organization of a BCT has led to a span of control problem in the rear area of the battlefield framework. In recent JMRC Rotations, BCTs have subordinated as many as eight platoon sized organizations to the Brigade Headquarters and Headquarters Company Commander, depending on the phase of the operation. While the preferred number of subordinate elements ranges between three and five, this condition proved difficult to manage. Terrain management and route usage became the most common challenges, but there were additional instances where managing security operations for the rear occurred. With the current ARSTRUC Structure, the Brigade Support Battalion commander represents an improved option to own the rear area. This Battalion has the preponderance of the assets in the rear area, as well as the staff to assist with management of the disparate operations that occur here. The authority associated with assigning a security task in the rear area to a headquarters with the analytical horsepower associated with a staff offers the opportunity for an improved outcome.

Without the necessary organic Brigade Protection capabilities, the rear area will remain vulnerable. Both echelons must effectively task organize with the required enablers to mitigate threats against friendly forces in the rear area. Committing forces to rear area security is not a waste of U.S. combat power, and given multinational formations, it should be a coordinated effort. However, commanders may remain reluctant to change the task organization to protect their rear area based on mission and priority. Therefore, units must adopt an innovative and flexible approach to rear area security. Lastly, Commands and staff at Division and Brigade must utilize a dynamic PPL that changes with the phase of the operation to identify vulnerabilities and align appropriate assets while managing risk.

Appendix A

References

1. FM 3-0, Operations, March 2025.

2. FM 3-96, Brigade Combat Team, January 2021.

3. FY 24 MISSION COMMAND TRAINING PROGRAM Key Observations (NO. 25-05 [946]), February 2025.

4. ADP 3-37, Protection, January 2024.

5. JP 3 – 10, Joint Security Operations in Theater, July 2019.

DISCLAIMER: This paper was produced with the assistance of GPT-based AI services for research, drafting, and/or editing purposes. While AI was utilized to generate or refine content, all information, interpretations, and conclusions presented herein are the responsibility of the author(s). The content has been reviewed for accuracy, originality, and compliance with ethical standards.

DISCLAIMER: Center for Army Lessons Learned (CALL) presents professional information, but the views expressed herein are those of the authors, not the Department of Defense or its elements. The content does not necessarily reflect the official U.S. Army position and does not change or supersede any information in other official U.S. Army publications. Authors are responsible for the accuracy and source documentation of material they provide.

Social Sharing