Imagine driving down highway 95 in southwestern Arizona. It’s sunset, not quite twilight yet, but you can see that night is quickly approaching. You’ve just passed a sign saying, “Yuma Proving Ground.” You’re near one of the most isolated military installations in the continental United States. You come up on Imperial Dam Road and taking it would take you head-first into the military installation. On the side of the road, you’re greeted with a “big” atomic cannon. You take a moment to marvel at this atomic marvel before driving north. Suddenly, you notice a large white barrel off to your right. It’s a cannon, something that looks like it’s from a video game, much larger than the one you just passed. What on earth could this be for? Is this for asteroids?

No, my dear reader, this gun is not for asteroids, and this isn’t a video game plot either. This gun is very real, and while you may not be able to see it locked and loaded, this gun sits idly on Yuma Proving Ground as a reminder of a very important progression in artillery and a testament to alternative means to reach outer space. This is a 16-inch High Altitude Research Project (HARP) gun, and it is one of only two that remain and one of three that ever existed.

The Cold War was an era of great uncertainty and technological marvel. It’s somewhat romanticized today as a period where novel ideas were formulated out of the minds that pushed us over the next echelon in technology. And why wouldn’t it? After all, the Cold War era of thinkers helped us push beyond the threshold of standing on Earth and finally make it onto the Moon. However, the ever-present threat of war meant that weapons systems also required innovation and attention.

Following the close of World War II, the Allies had captured two of the large Krupp K5 240-mm guns used by Germany. These guns were named Annie and Leopold, respectively. Effectively, these guns were transported by the Germans on rail where they dealt devastating firepower to the Allies. Following the defeat of the Axis in 1945, both guns were shipped back to Aberdeen Proving Ground where they were analyzed. The intention was to replace the M1 240-mm gun that the U.S. had in its inventories. However, the dawn of atomic warfare also brought new chilling concepts and requirements. Two problems were presented.

First, how can the stability of a large gun be improved? The K5 had modest stability that made its firepower as accurate as it was devastating. Second, how small can you make an atomic device? After all, the Mark III atomic bomb weighed over 10,300 pounds and had a diameter of over 1.5 meters – comparable to the size of a small sedan.

Picatinny Arsenal, New Jersey was given the task of overcoming these obstacles. The decision was made to increase the caliber of the gun to 280-mm. Meanwhile, there was also the issue of the carriage to place the gun on that would provide stability while detaching the gun from the restrictions of rail. The T72 carriage was designed with input from Rock Island Arsenal. The gun tube was supplied by Watervliet Arsenal, New York. The combined system was to be transported by two tractors like the pilot and steering rail cars used by the Germans. The complete T72 carriage and T131 gun combined into the M65 280-mm heavy motorized gun, affectionately known as “Atomic Annie” – the world’s first atomic artillery piece.

The M65 was designed to be deployed in a series of batteries while being just mobile enough to be moved if needed. The intention of using these guns was to either launch high-caliber and high-explosive shells to distances as much as 20 miles away. Alternatively, it was designed to launch atomic projectiles up to 17 miles away in tactical use. Such blasts could cover for a retreating force, provide a barrier for an advancing force, or even change the tide of battle on the tactical level. While capable, the M65 only ever fired conventional rounds of ammunitions save for once.

On May 25, 1953, the M65 participated in a series of nuclear research tests known as Upshot-Knothole. The specific test, known as “Grable,” tested the atomic firing capabilities and viability of Annie. The blast yielded by the shell was approximately around 15 kilotons of explosive power: equivalent to the blast over Hiroshima just eight years prior. It was the only time an atomic shell was fired by an artillery system. Following this successful test, around 20 other M65’s were produced, although the exact number isn’t known. Most of them were deployed to Germany and Okinawa, with the latter being kept for staging in the event of further conflict in Korea. However, their size made them obsolete almost immediately after fielding.

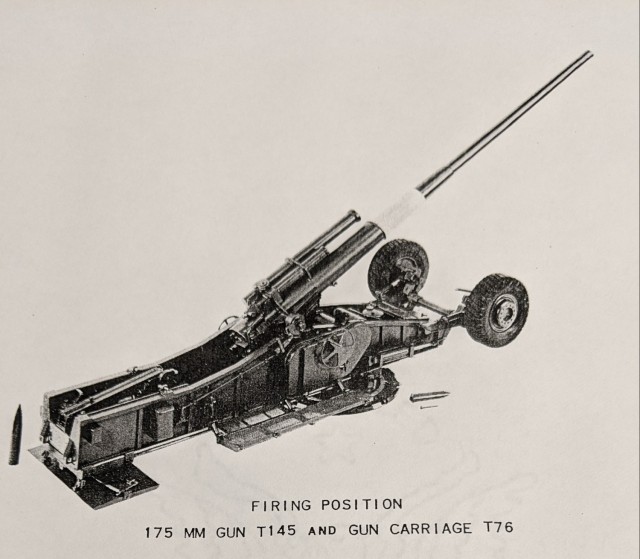

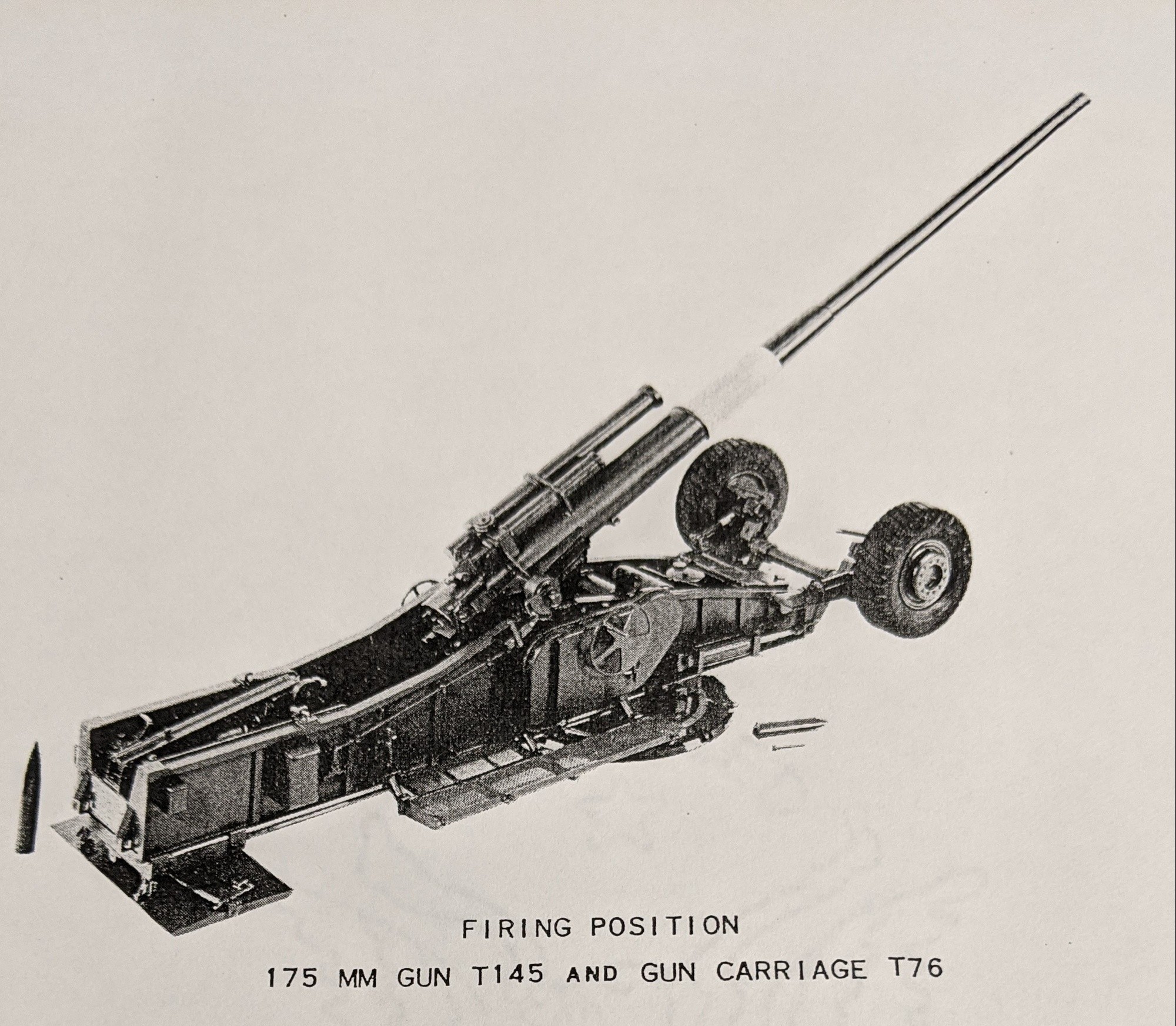

By the mid-1950s, the U.S. Army was experimenting with a carriage that was modular and capable of being used as the platform for multiple guns. The T76, also known as the Triple Threat Weapon Carriage, was designed to carry the 240-mm and 203-mm howitzers, and the 175-mm gun. The T76 took the old T72 design and made it lighter, better equipped for deployment over roads, and capable of being transported by a single prime mover. According to a study conducted by the Franklin Institute for Research and Development on June 15, 1955, the intent was to improve mobility and maneuverability of high-caliber weapons that had a range of 35,000 yards.

The study went on to state that a triple threat weapon will “combine all three cannon[s] on a single carriage.” This would be done by “modifying tipping parts of the three cannon and the [existing] 175-mm gun carriage.” According to drawings, the carriage served as the base, while two recoil mechanisms were to be produced. One for the 240-mm howitzer, and another would be used for both the 203-mm howitzer and 175-mm gun.

This also reduced emplacement time to as little as 10 minutes, down from the M65’s emplacement time which was as much as 30 minutes.

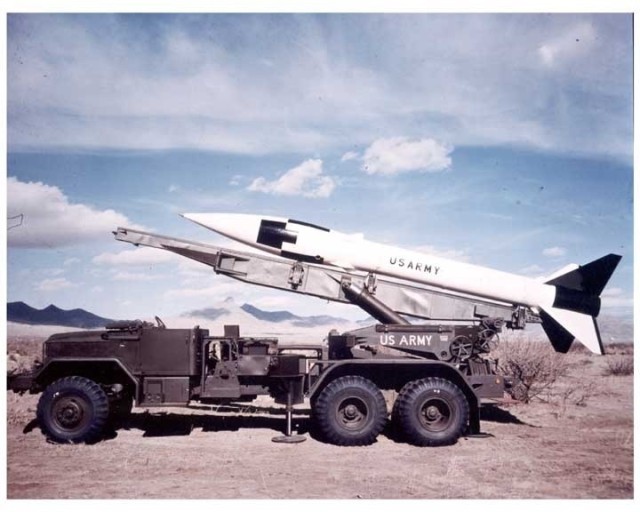

In addition, medium range rockets were slowly making the need for larger atomic-capable weapon systems obsolete. The 1961 deployment of the M38 & M39 Davy Crockett recoilless rifle also made atomic devices much more portable for tactical use. Furthermore, devices were small enough to be placed on more standard and compact 155-mm artillery shells. While the T76 proved useful for the emplacement of multiple weapon systems on a single carriage through modularization, the gun systems continued to evolve. The carriage’s weight also proved to make it obsolete, as newer and lighter gun carriages enabled the rapid fielding of guns transported by helicopter or even simple auxiliary power.

But it’s hard to let go of passion projects and scientific marvels sometimes.

Starting in the mid-1950s at the peak of the research on compacting of atomic devices, project HARP was a novel research program designed to study the feasibility of launching projectiles high into the atmosphere and low orbit. HARP served a multitude of functions for multiple agencies, both in the defense and scientific research communities. The Canadian Armaments and Research Development Establishment (CARDE) began collaborations with the Ballistic Research Laboratory (BRL) to drive the project forward. The T131 gun tube from the M65’s was considered for the program, but ultimately the larger 16-inch naval gun was used. Meanwhile, the smaller five and seven-inch guns were married to modified T76E1 carriages. The T145 gun was used in the seven-inch design. There were two specific areas of research being conducted with several supporting efforts.

The Cold War came with a plethora of challenges for offensive and defensive weapons.

HARP was able to launch projectiles high into the atmosphere; over 110 miles (580,800 feet). For comparison, the highest-flying aircraft flew to just under 97,000 feet, and that wasn’t until 2001, and the Karman Line (the line that separates the atmosphere from outer space) resides at an altitude of 327,360 feet. This meant it was perfect for studying how the environment of low or zero gravity had on a projectile. Studies were conducted surveying how such a high altitude modified a projectile or re-entry vehicle. This research proved vital in the development of ballistic missiles and even some space programs.

Chief among the CARDE and BRL’s concerns was that of ballistic missile defense. Not only did the improved technology of short-range and medium-range rockets pose a threat, but the threat of fully fledge intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in 1957 pushed the need for intercept to the front of the mind of many defense specialists. Ideally, an ICBM or rocket launch would be prevented on-site, but late intercept could prove to be risky or fail altogether.

Aircraft could only fly so high to conduct an intercept on-site or at the re-entry point and using a countering missile proved to be a shaky bet at best. However, if an ICBM could be intercepted in orbit, this would remove the risk to the population at large. A high-powered weapon would be capable of intercepting a warhead before it could separate.

In addition, the project looked to test the feasibility of launching vehicles into orbit without the need of propellant within the atmosphere. This would allow space launches to be more economical, according to one researcher.

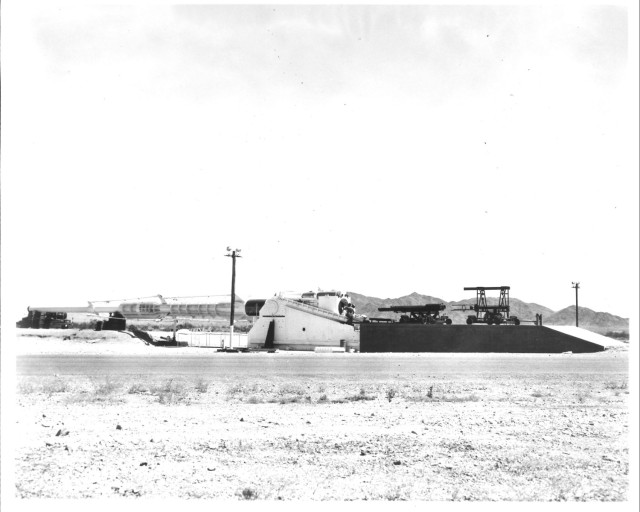

To accomplish such altitudes, a high-powered gun that was capable of firing projectiles high into the atmosphere was required. Therefore, the Army selected the T131 gun to serve as the basis for the original 16-inch HARP gun. Subsequent smaller models experimented with how sabot designs interacted with the atmosphere and the rapid launch of both “dumb” and “automatized” vehicles. These sabots were protective shields that fit around the projectile and carried it down the barrel of the gun. Three 16-inch HARP guns were fabricated and provided to BRL for use in the project. These guns were not mobile and stationary in place in Barbados, Yuma Proving Grounds, and Montreal.

All the guns were smooth-bore and extended to provide additional velocity to reach the intended altitude.

On November 18, 1966, the BRL operated 16-inch gun at Yuma launched a sabot and vehicle to over 580,000 feet. This set a world altitude record for any projectile fired by a gun, and it is one that still stands today. The projectile left the muzzle of the gun at almost 4,700 miles per hour – over Mach 6.

Despite the successes of HARP in delivering projectiles high into the atmosphere and orbit, focus shifted to missile and rocket technology. Furthermore, the ongoing war in Vietnam had taken money and focus away from the project. Eventually, both the United States and Canada withdrew from the program. Nevertheless, HARP had collected large amounts of valuable data on the atmosphere and conditions in low orbit. These contributed greatly to atmospheric research coupled with other materials collected by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) for use in future spaceflights.

Eventually, the project ended, and by 1970 HARP had become a memory. One gun remains in Barbados on the coast where it is gradually rusting and will one day inevitably turn to dust. It is a relic from an era gone by. Meanwhile, the HARP gun you passed on the highway, unbeknownst to you, and kept in the best condition of the two remaining, is nothing short of a historic reminder of the power of artillery.

As the years ticked by, smaller, lighter, and more efficient weapon systems have replaced HARP and the atomic giants of the past. Howitzers and guns are light enough to be whisked away by a helicopter, and modular enough to be placed on loitering aircraft. The atmosphere can be sampled by radiosondes and balloons. Space can be touched with reusable rockets. As technology progresses and time moves on, so too does history – and so do you on your way down the highway to the next destination.

Social Sharing