A mobile training team assigned to the U.S. Army Security Assistance Training Management Organization recently provided four weeks of intense medical and small unit tactics instruction for members of the Papua New Guinea Defense Force.

The March 17 through April 11 training marked SATMO’s third Papua New Guinea MTT in the past year, having previously worked with the PNGDF on armorer, Combat Life Saver, Tactical Combat Casualty Care, and SUT courses.

The security assistance training is a result of the Defense Cooperation Agreement between the United States and PNG signed in 2023. The impact of this face-to-face security assistance training supports the DCA by enhancing security cooperation and improving the capacity and interoperability of the PNGDF.

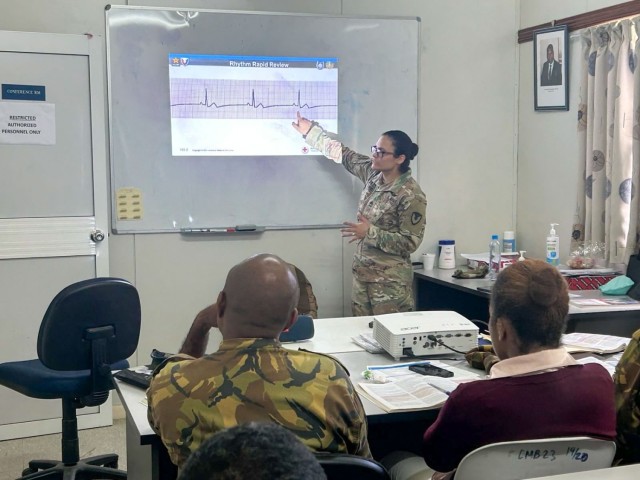

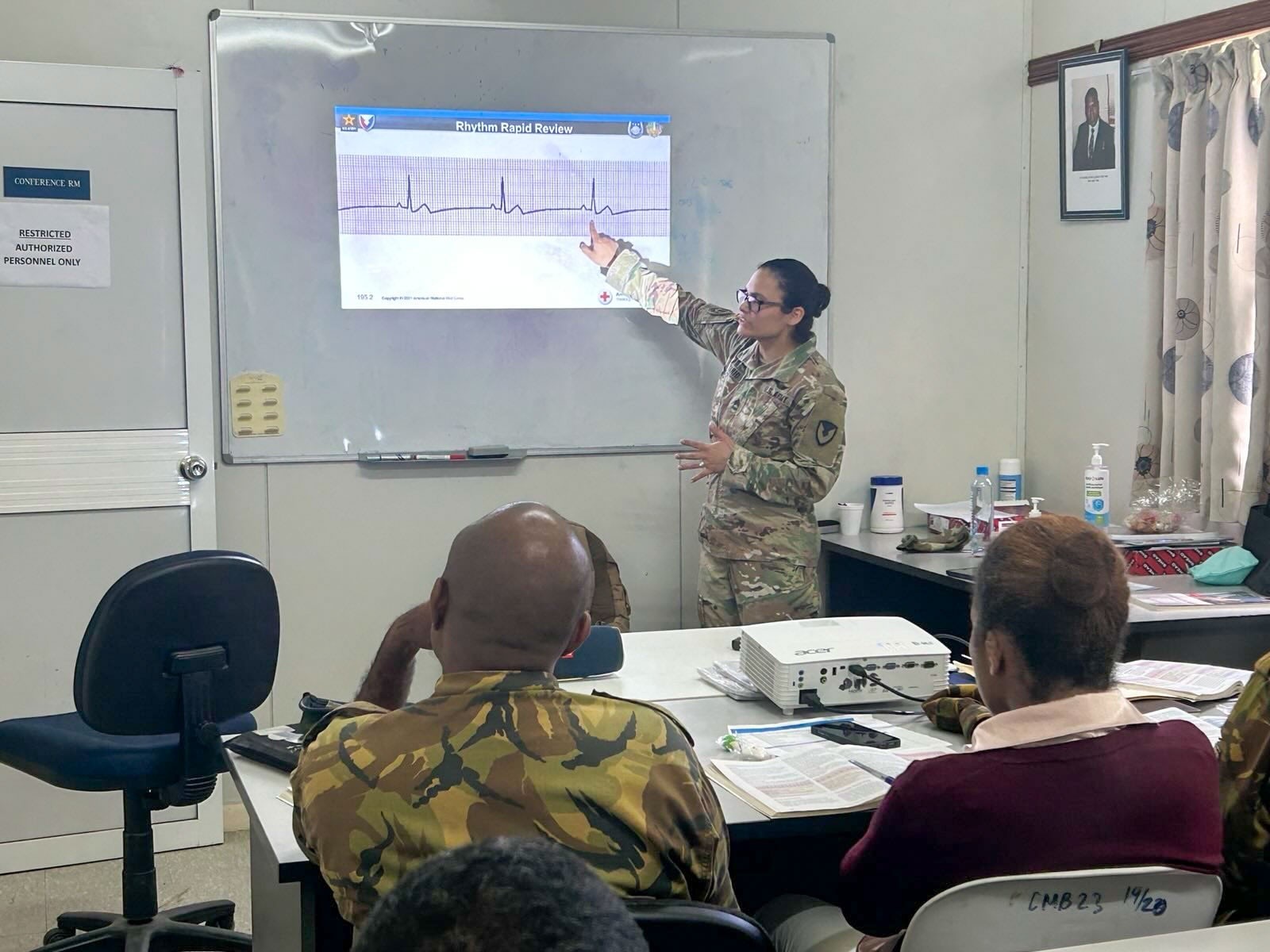

Participating in her second PNG MTT, Sgt. 1st Class Jenny Tario served as the medical team lead for this iteration as she and Master Sgt. Joseph Binan led PNGDF land force soldiers in Basic and Advanced Life Support instruction and Limited Primary Care.

“The first and second weeks were BLS and ALS training, and both ended with 25- and 50- question tests that required an 80% or higher to pass, which everyone did on the first attempt,” said Tario. “The third week was focused on LPC, which included dermatology, gynecology, muscle, skeletal, and common respiratory illnesses.”

The classroom instruction and practical exercises and assessments throughout those first three weeks culminated in a two-day field training exercise in conjunction with the SUT course where PNGDF personnel responded to varying levels of injury and illness scenarios in the mountainous terrain and warm climate of Port Moresby.

“Overall, the soldiers were very enthusiastic with all of the training,” said Tario. “They were very receptive and asked a lot of questions. They wanted to understand everything, which was pretty refreshing.”

At Goldie River Training Depot, about 45 minutes from Tario and Binan, Master Sgt. Hans Moeller and his team guided members of the 1st Royal Pacific Islands Regiment through an SUT course.

Small unit tactics encompasses a litany of tactical skills needed in the operational environment such as combatives, weapons familiarization, patrolling operations, and Tactical Combat Casualty Care, but for this specific course, Sgt. 1st Class Shea Myatt said the standards were enhanced.

“The intent of this course was to try and stand up something similar to the Army Ranger School,” said Myatt. “The first week we gauged where they were at physically, so we had them do a (physical fitness) test, a 15-kilometer, 15-kilogram ruck march, and a five-kilometer run in 30 minutes.”

The 1RPIR soldiers were also tested on their water survival and land navigation abilities before proceeding to the instructional portions of the course.

While the course was aimed at team and squad leaders from the regiment, Myatt said that the course ended up consisting of who was available -- mostly privates to lance corporals -- which made for a learning curve in some respects.

“A lot of them had never received training at this level, and most were not in leadership positions in their unit,” said Myatt. “While we did base this off of the Darby phase of Ranger School, it was much more like a tactical noncommissioned officer education system course.”

Despite the curve, the course marched forward and weeks two and three brought about a myriad of tactical lessons leading up to a three-night field exercise.

“For a total of four days of training, we pushed them into leadership positions at the squad level and assessed them based on their planning abilities and leadership while out in the field,” said Myatt. “We gave them specific missions and they would have to form a plan for each. In the morning time, they would brief us what their plan was, and we would leave for the mission.”

While the field exercises were led by the PNGDF soldiers, the training team was embedded with them throughout the entirety of the process to observe and assist or correct as needed.

“From a physicality standpoint, the course was too short to notice any improvements, but as far as the information, we definitely noticed large improvements,” said Myatt. “As they understood what we were teaching, they started understanding expectations and they started to rise to some of those levels.”

The medical and small-unit tactics training didn’t come without their challenges, though. Tario and Moeller’s teams had to improvise in lieu of unavailable equipment or adapt to equipment or methods that differ from the Army standard.

“Some of the physical therapy students had no prior history of cardiac, so I did a day of instruction based on (echocardiogram) reading and cardiology to give them a foundation,” said Tario. “We ran into an issue, though, of trying to get a cardiac monitor to illustrate what they should be looking for.”

Not to be deterred, Tario relied on videos for static ECG readings and other cardiac monitoring to effectively illustrate foundational concepts of what the PNGDF personnel should be looking for.

For the small unit tactics cadre, certain cultural differences and the discrepancies in weapons systems and equipment availability required flexibility to abide by Army doctrine while ensuring their training lessons were relevant to the resources the 1RPIR had at their disposal.

“An easy example was trying to teach land navigation with MILS instead of degrees,” said Moeller. “That’s completely foreign to us and we had to catch ourselves multiple times.”

Moeller also noted weapons differences and how that impacted training. For example, the PNGDF employs the STK 40mm automatic grenade launcher whereas the Army uses the Mk 19, so the cadre had to adjust instruction to account for different rates of fire and other performance factors in relation to certain scenarios.

While both training courses provided crucial knowledge and skills for those who attended, the larger goal of these PNG MTTs is to establish a foundational knowledge base that the PNGDF can use to build internal doctrine and training to modernize and improve their deterrence and security capabilities.

“Overall, these training teams are improving our relationship with Papua New Guinea and the Papua New Guinea Defense Force,” said Moeller. “We are going to see operational impacts down the road, but not immediately. They are trying to take this training and implement it and update their doctrine and how they operate, but it’s going to be a multi-year, long-term effort.”

Moeller said leadership there is enthusiastic about the training SATMO has provided thus far and the prospect of working with them in the future and growing that interoperability in the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command area of responsibility.

Social Sharing