This year, the U.S. Army Infantry Branch celebrates 250 years since its creation by the 2nd Continental Congress. Several events commemorating the anniversary are planned throughout the year at Fort Benning, GA, and around the world by infantry units.1

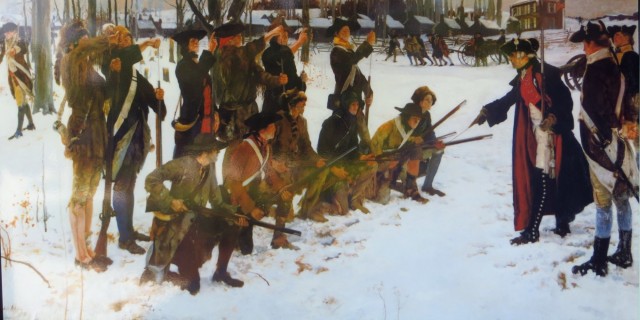

Upon receiving the news that New England militia resisted British regular troops at Lexington and Concord, MA, the 2nd Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, decided that the rebels required a formal military organization. On 14 June 1775, Congress passed an act creating a “Corps of Riflemen” to act as skirmishers and light infantry to scout and screen in front of the main army in the field. The next day, the representatives appointed George Washington as Commander in Chief and directed all Patriot efforts to support the American forces surrounding Boston. These riflemen served as the first formal unit of the Revolutionary Army and ensured that the first troops in the American Army were Infantry Soldiers.

Wednesday, 14 June 1775

"The resolutions being read, were adopted as follows:

Resolved, That six companies of expert riflemen, be immediately raised in Pennsylvania, two in Maryland, and two in Virginia; that each company consist of a captain, three lieutenants, four serjeants, four corporals, a drummer or trumpeter, and sixty-eight privates.

That each company, as soon as completed, shall march and join the army near Boston, to be there employed as light infantry, under the command of the chief Officer in that army.

That the pay of the Officers and privates be as follows, viz. a captain @ 20 dollars per month; a lieutenant @ 13 1/3 dollars; a serjeant @ 8 dollars; a corporal @ 7 1/3 dollars; drummer or [trumpeter] @ 7 1/3 doll.; privates @ 6 2/3 dollars; to find their own arms and cloaths.

That the form of the enlistment be in the following words:

I ____ have, this day, voluntarily enlisted myself, as a soldier, in the American continental army, for one year, unless sooner discharged: And I do bind myself to conform, in all instances, to such rules and regulations, as are, or shall be, established for the government of the said Army."2

Originally, the congress specified that the rifle regiment comprise six companies from Pennsylvania and two each from Maryland and Virginia; however, the desire to march north by American riflemen resulted in 13 companies being created by the time the long hunters arrived around Boston.

The recruits for the new command applied for enlistment in a unique manner. Those appearing for muster brought their own rifles and ammunition and wore their own hunting “cloaths.” Handmade by riflesmiths, their weapons required custom bullet molds as they ranged from .40 to .80 caliber. In a variation of the local “rifle folic” matches held along the frontier, communities held rigorous competitions to select the best of the regional shooters. To gain acceptance in the rifle companies, each rifleman had to fire at a human-sized target from 100 yards away. Many of the frontiersmen easily performed this feat, so many companies marched with more than the 100 Soldiers specified.

On the outskirts of many towns on the route to Massachusetts, the recruits held rifle demonstrations to showcase their marksmanship skills. For hunters and townspeople, the accuracy of the shooting far surpassed others’ ability with musket or fowling piece. The feats of accuracy and range impressed the citizens providing food and drink to the new Whig warriors as they marched to join the volunteers surrounding the British Regulars in Boston.

Marching overland to join in the Siege of Boston, General Washington welcomed the frontiersmen and planned to use them as sharpshooters and to patrol and raid around the enemy. Within months, the Pennsylvania companies combined to create a regiment, and other volunteer rifle companies took their place. The regiment grew as states raised additional companies, and the long-term unit commander, Daniel Morgan, led a battalion of these marksmen into Canada in the fall of 1775. Though the Patriots failed to win over the largely French colonists in the north and defeat the British garrisons around Quebec, the force returned and joined the rest of the Continental Army facing British and Hessian mercenary troops of the Crown around New York City in 1776.

Around the time that Washington’s Army fought the battles of Long Island, Brooklyn Heights, Fort Washington, and more, the troops listened as leaders read a draft of the Declaration of Independence. These Soldiers realized that they no longer struggled only for their rights as British citizens but fought for the independence of a new nation. Their strengthened resolve kept the Patriots in the Army through a series of defeats from New York, across New Jersey, and around the capital of Philadelphia. Just as Soldiers’ enlistments approached their end, Washington ordered the Army to cross the ice-choked Delaware River in the dark to capture a Hessian detachment at Trenton. Returning across the river a few days later by another route, Washington led the rejuvenated troops to capture the British supply depot at Princeton, NJ. While many of the victorious troops returned to their homes after valorous service, others reenlisted and joined new recruits to continue the fight to free America from British rule.

The Rifle Regiment fought in battles for independence from Saratoga, NY, through Cowpens, SC, to the last major battle at Yorktown, VA. Used as skirmishers in front of the battle line, the riflemen conducted patrols and raids, serving as the first United States Rangers. The 2nd Continental Congress founded other specialized units that evolved into the other branches now serving in the U.S. Army. While 14 June is proudly recognized as the birthday of the Army, the Corps of Riflemen set the precedent of the Infantry serving as the first branch of the U.S. Army.

Notes

1 To access U.S. Army Infantry School official social media accounts, visit: https://www.facebook.com/usarmyinfantryschoolUSAIS/ and https://www.instagram.com/usarmyinfantryschool/.

2 Journals of the Library of Congress, 1774-1789, Volume II, 1775, May 10-September 20, Library of Congress, edited from the Original Records in the Library of Congress by Worthington Chauncey Ford, chief, Division of Manuscripts, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1905), 90, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llscd/lljc002/lljc002.pdf.

Dr. David S. Stieghan serves as the U.S. Army Infantry Branch Historian at Fort Benning, GA. His published works include editing the reminiscences of Doughboys in World War I, Over the Top! and Give ‘Way to the Right!

This article appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of Infantry. Read more articles from the professional bulletin of the U.S. Army Infantry at https://www.benning.army.mil/Infantry/Magazine/ or https://www.lineofdeparture.army.mil/Journals/Infantry/

Social Sharing