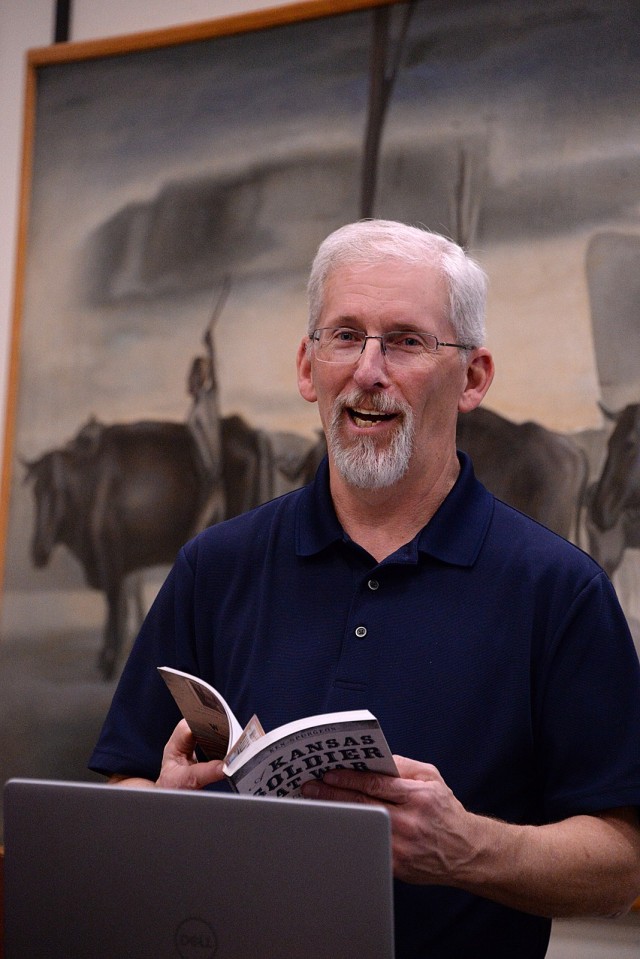

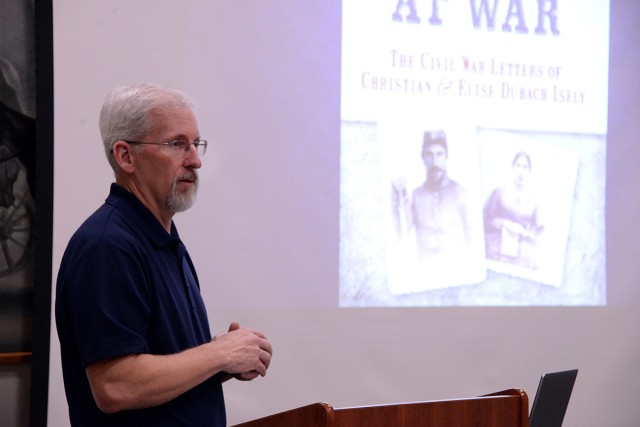

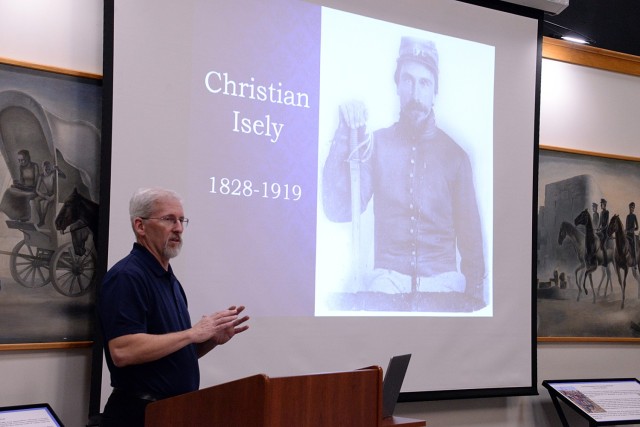

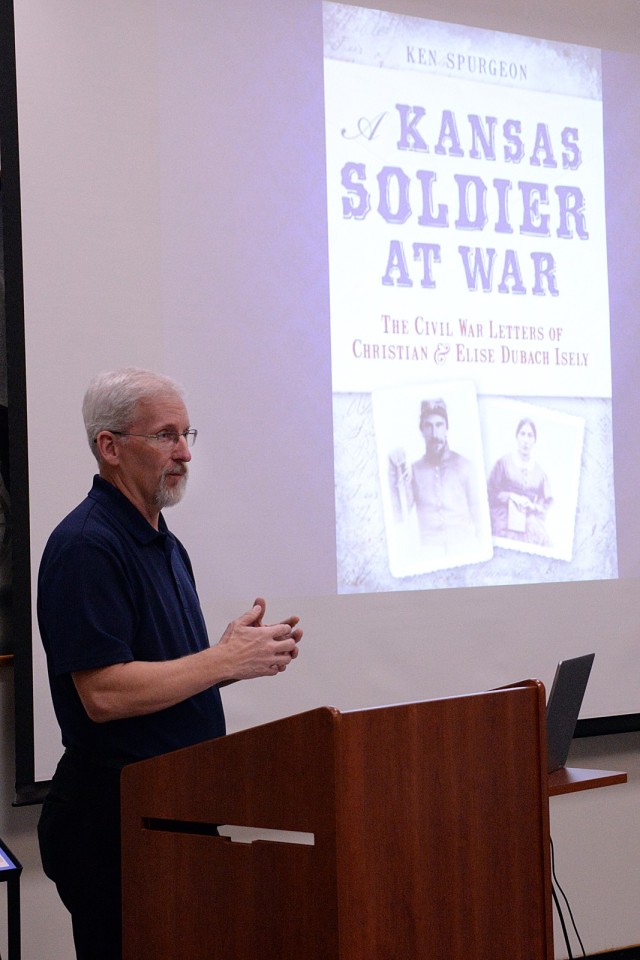

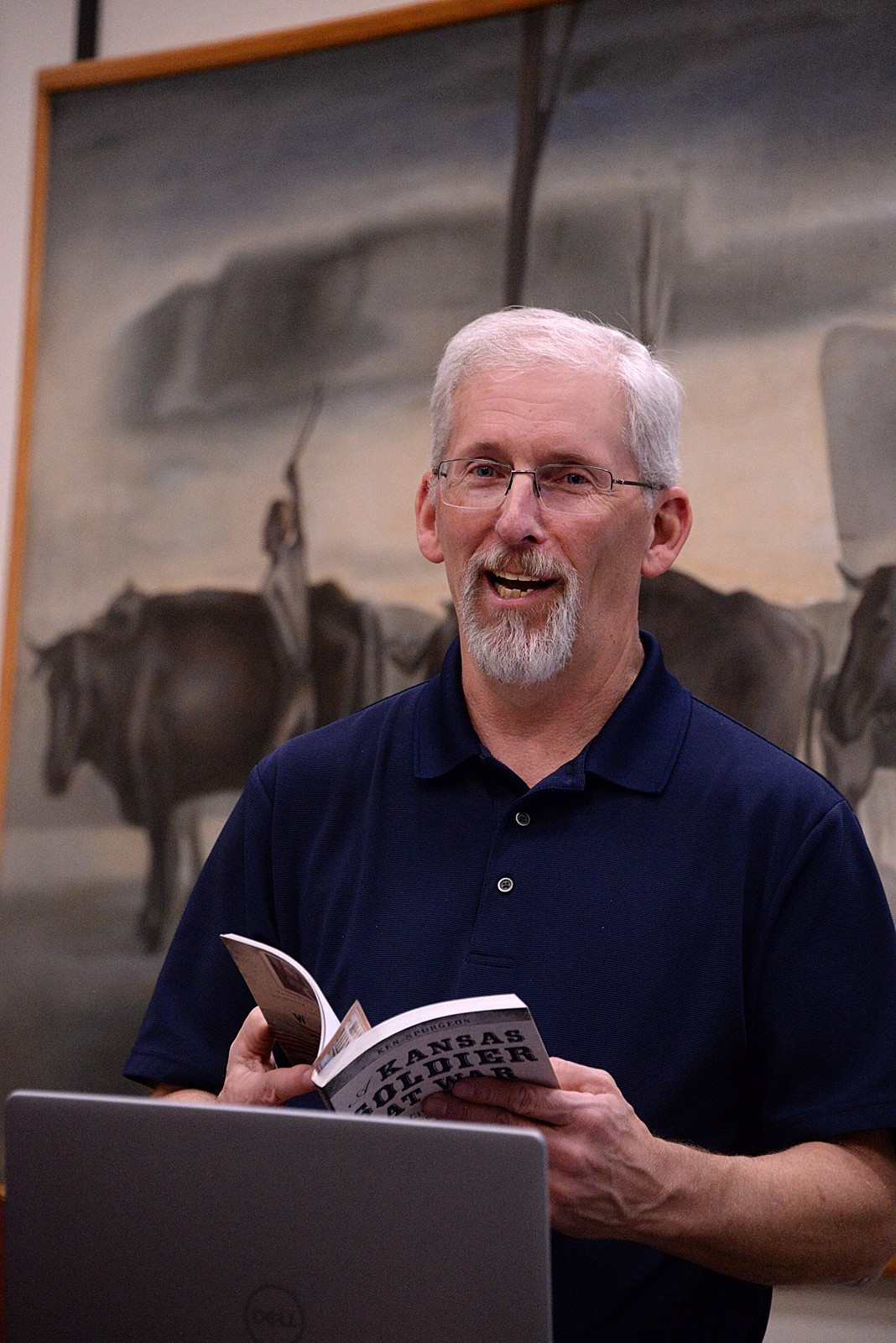

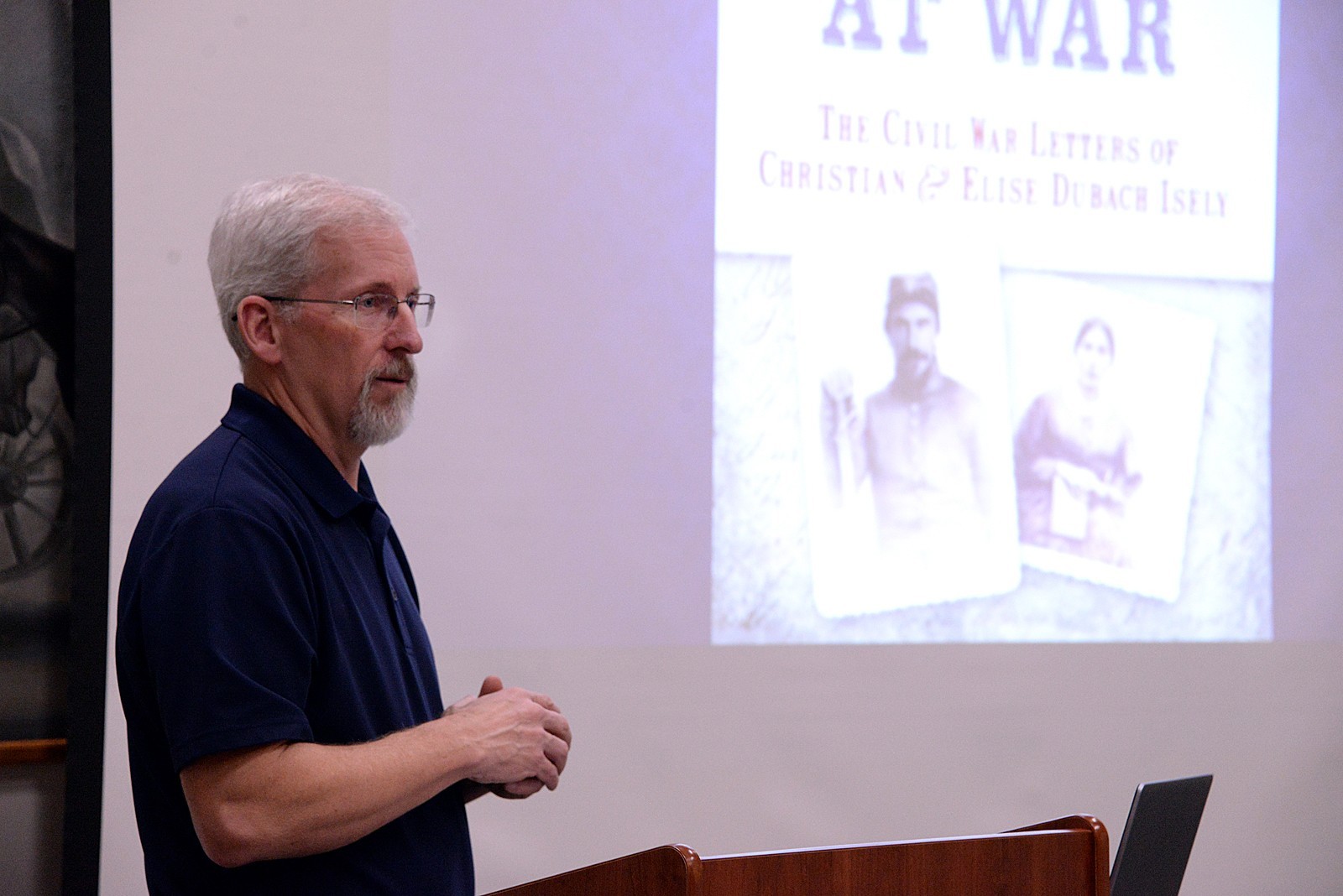

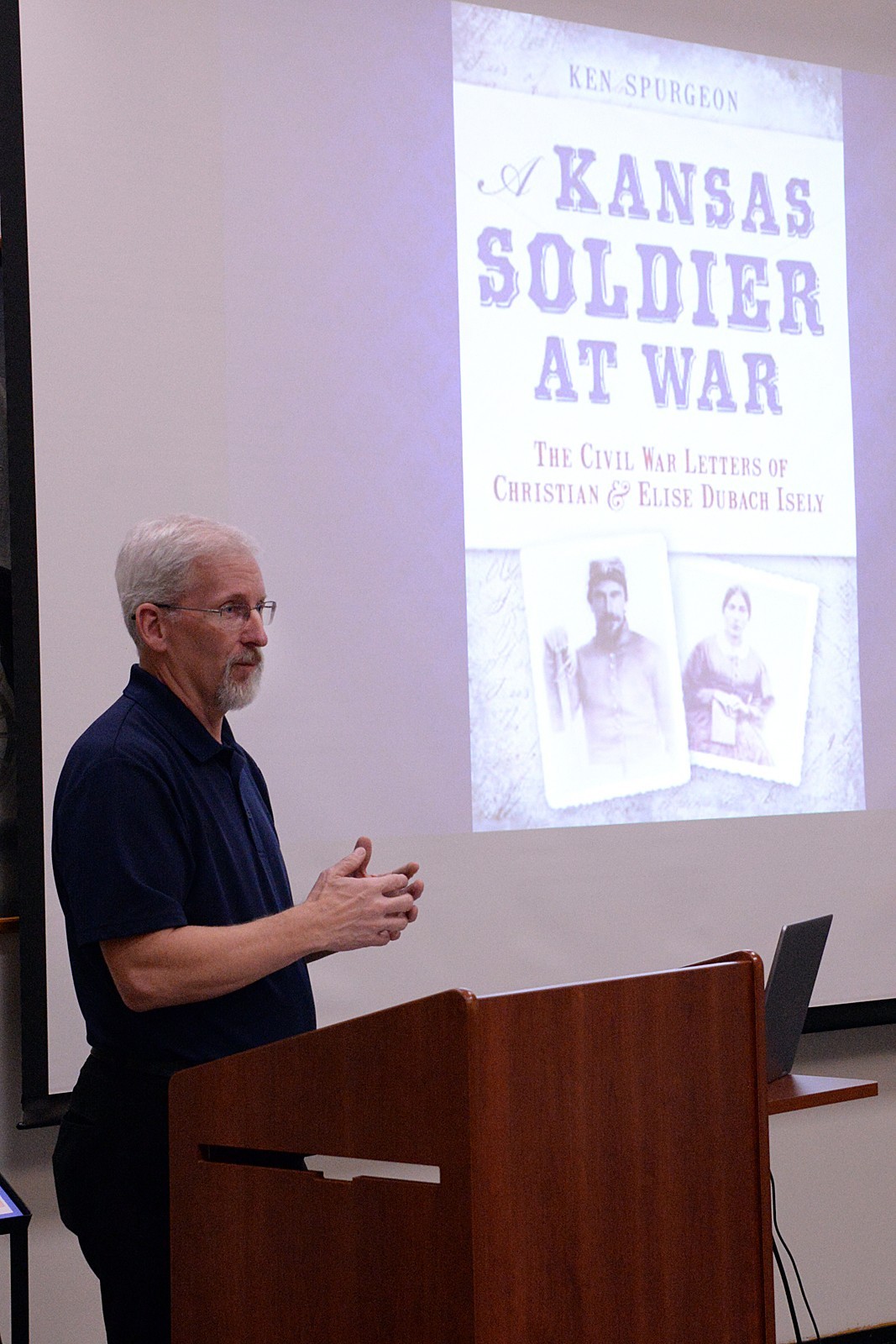

FORT LEAVENWORTH, KANSAS — Ken Spurgeon, assistant professor of history at Friends University in Wichita, Kansas, presented the Friends of Frontier Army Museum speaker series lecture Feb. 26, 2025, about his book, “A Kansas Soldier at War: The Civil War Letters of Christian and Elise Dubach Isely,” and the inferences that can be made through those letters. Isely was stationed at Fort Leavenworth for about 18 months, from October 1861 to April 1863.

Spurgeon, whose great-great grandfather was in the 9th Kansas Cavalry, told the audience that he has special interest in Kansas Civil War history.

“One of my two things that got me excited about history when I was a kid was when my grandfather showed me his grandfather’s gun, which was a ‘63 Spencer, which I have and I’m grateful to have it,” Spurgeon said. “(My grandfather) never knew his grandfather — his grandfather died at 34 — and so they were all just stories and we had a little family diary, but I remember as a kid just being completely into what happened to that guy, where was that gun at, and all that, so I was just obsessed.”

When working on his master’s degree at Friends University about 25 years ago, Spurgeon was introduced to the Isely Collection, which contains about 300 letters written between Isely and his wife and other family members. The letters became the basis for his master’s thesis, from which the book developed about 10 years ago.

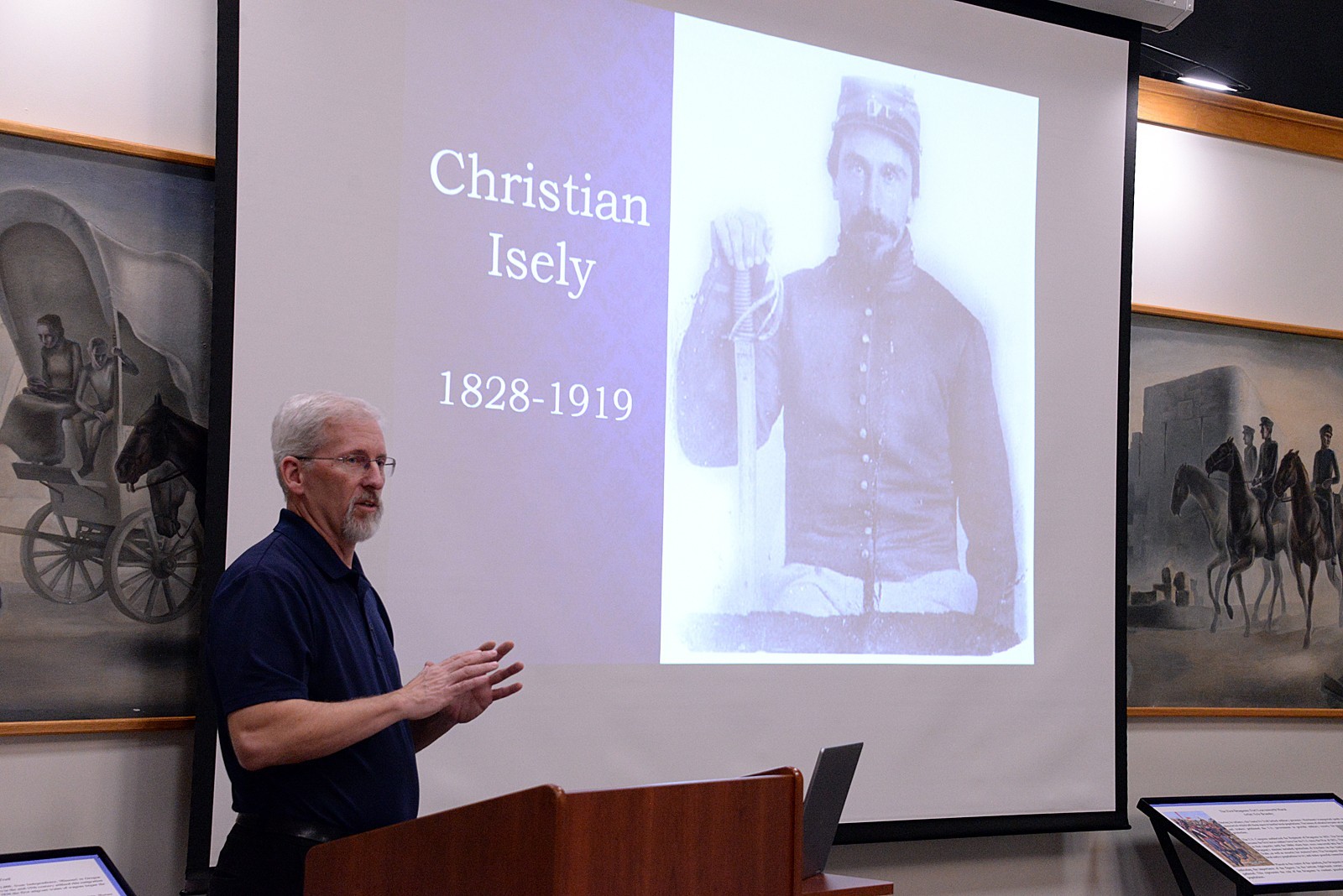

After growing up in Ohio, Isely met fellow Swiss immigrant Elise in St. Joseph, Missouri. The couple was married in May 1861, just as the Civil War was starting.

“When you dig into this kind of stuff, they didn’t know we were going to read it… They were very impacted by slavery,” Spurgeon said, sharing a story about Elise witnessing a mother being sold separately from her son, and noting where the couple’s families stood politically.

“It’s the summer of ’61, war is happening, Christian is being told by his family ‘This is not our fight,’ and you can see through his diary he is really processing,” Spurgeon said. “The changing point was October of ’61 — the war has gone on for about five months, units are moving, Leavenworth is bustling, and St. Joe was going back and forth between Union and Confederate.”

Isely decided to join the fight after meeting Union soldiers from Ohio, realizing that someone from his home area was patrolling, policing and protecting him.

Isely joined Company F, raised by Hugh Cameron — whom Spurgeon said Isely described as really wacky — of the 2nd Regiment, Kansas Cavalry, commanded by William F. Cloud — whom Elise described as the best-looking man she’d ever seen.

“In his diary, Christian says ‘Captain Cameron, not so much; Colonel Cloud, awesome,’” Spurgeon paraphrased. “And so, he’s in and he reports to Fort Leavenworth, which by all accounts, he’s going to be here for a month or two and then, we’re off to the war, you know how it was, everybody was eager (to get to the fight.)”

Spurgeon said Isely wrote honest assessments, including that Camp Lincoln at Fort Leavenworth was “full of lots of good men but (also) lots of drunks.” He said soldiers were eager to get from the camp and onto the war, but Isely got sick and was left behind.

“His regiment went away without him, and he was left here. That one month, two months maybe, turned into 18 months. He didn’t miss the war, but he did miss out on some battles his unit was in.”

Spurgeon said Isely became a nurse while he served at Fort Leavenworth, and he hated it.

“Because it’s not what he felt he signed up to do, and he wanted to fight — he felt like he was evading the war, somehow, even though it was not his choice at all.”

The situation, however, allowed Isely to observe daily life at Fort Leavenworth.

“One thing he said was, of course, the good units and the good regiments and the good men, they were here, he met them, he liked them, but then they were gone, they were off to war. And so, he felt like what he kept being around was some of the not-so-good people, and that’s what really frustrated him about it all.”

Spurgeon said Isely and his wife had a strong faith, and that in his letters, Isely tells Elise about his “sweet spot of prayer” somewhere on post.

“He had some spot he went to, he’ll talk about it time and time again … ‘This happened and I went to my sweet spot of prayer.’”

The letters and diaries explain what was happening in the couple’s families’ lives at the time as well, including Isely’s parents still against serving in the war and his youngest brother Henry’s decision to serve.

“In family connections, the most interesting letters are from Henry and Christian,” Spurgeon said about the brothers sharing their experiences serving at different places, as well as their politics — Henry’s staying steady and Christian’s evolving.

Year of heartbreak

In 1862, with Elise in St. Joseph and Isely barely able to go see her, their first child was born, but the baby died unexpectedly about two weeks later.

“There are a lot of letters about that loss,” Spurgeon said. “They don’t know the future, they are saying in the letters ‘I may never see you again, we may never have another child,’ and there is a lot of heart-wrenching stuff about the baby.”

Elise’s 17-year-old brother, Adolph Dubach, whom the baby was named for, joined the 5th Kansas Cavalry near Fort Scott, Kansas. Isely received a letter from a cousin that his brother in law was very sick, but he wasn’t granted leave to go to him until more than a week later.

“He thinks he’s going down toward Fort Scott… He ends up going close to Lawrence… Believe it or not, he finds his brother in law (near Baldwin City),” Spurgeon said. “The boy has been discharged … The boy is as sick as can be. The boy heads north, Christian heads south … Christian found him two days before the boy died.”

Pursuing bushwhackers

Spurgeon said in April 1863, Isely began pursuing guerilla fighters called bushwhackers.

“He does get in a couple skirmishes, but most of his military time, the next year and half, is pursuing, pursuing, pursuing bushwhackers. It’s life in the saddle.”

About that time, Isely sent Elise to Ohio where he thought she would be safer with his parents, who were anti-war and anti-Lincoln.

“There are letters Elise writes Christian and she says ‘Are your parents Christians at all? Because they are some of the most hateful people I’ve ever met. Are you sure you’re related to them?’” Spurgeon paraphrased, noting the sentiment could be applied to present-day relationships. Elise would be back in St. Joseph by the time the couple reunited in 1864.

About two months after Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence, in fall 1863, Christian’s tentmate was killed. Spurgeon described this as a tragic experience for Isely, which included being unable to later find the man’s burial site.

“It’s a different time, you really have to be paying attention, you’re asking the question ‘How much combat did he see?’ and all those kinds of things,” Spurgeon said. “Christian tells us in one letter what happened to one bushwhacker he came into contact with. Shortly after (his tent mate’s) death … he says ‘Today we got a trail on the bushwhackers … We caught up with a few of them. Don’t you think we knew what to do.’”

In September, a few months before Isely was medically discharged in Arkansas in 1864 and headed north on a refuge train, he wrote a letter that Spurgeon projected an excerpt from on screen for the audience to read.

“He’s thinking about the cause, he’s thinking if he’s ever going to see Elise again, he’s thinking about his buddy he buried, he’s thinking about his family in Ohio that give him crap all the time for fighting,” Spurgeon said.

“‘There are persons who would sneer at, and condemn my sentiments; but I thank God, although such would uphold slavery and fetter the mind, I am not their slave yet,” Spurgeon read from Isely’s letter. “‘I do not want their favors. I care not for their frowns, but will do my duty to my God and my country, regardless of their secret midnight meetings, their conspirings against us, to contemplate our overthrow. Of my work I am not ashamed, nor afraid to do it in open daylight, because it is the work of humanity, justice and right.’”

When Spurgeon was working on the book, his daughter told him that Elise was the star of the story, not Christian.

“One of the unique pieces of the story is you didn’t just have a soldier’s letters home, you had all of the letters that she wrote to him,” Spurgeon said. “He kept all of those letters in his saddle bags.”

Spurgeon said Isely was so far ahead of his time, asking his wife to describe a day in her life and encouraging her to go to school if she was bored.

“This is pretty amazing stuff for that time. He was trying to figure out what craft could she learn, and I mean not in a pushy way, but more ‘What would you like to do?’”

The original letters, which Spurgeon referred to as “jewels of information,” are housed in the special collections at Friends University. For more information on the letter collection, visit https://archivesspace.wichita.edu/repositories/3/resources/186.

To hear Spurgeon’s entire FFAM presentation, visit https://www.facebook.com/ftleavenworthffam/.

Visit the Frontier Army Museum’s Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/FrontierArmyMuseum for information on upcoming events, including the FFAM speaker series, history brunches and Spring Break programming at the museum.

Social Sharing