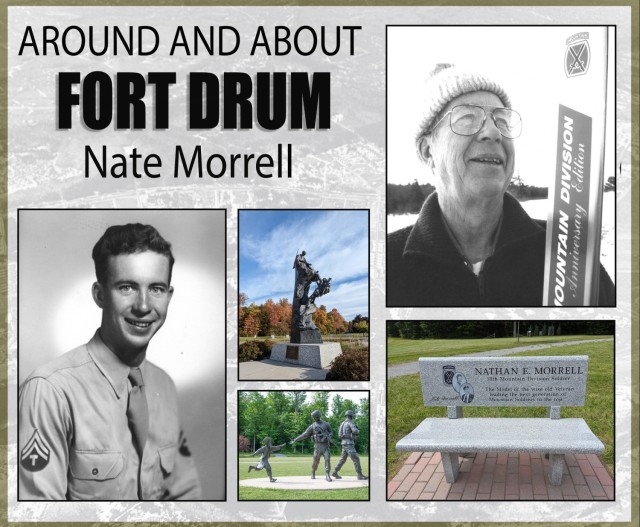

FORT DRUM, N.Y. (March 6, 2025) -- Among the monuments, memorials, and plaques in Memorial Park is a bench bearing the name Nathan E. Morrell – a 10th Mountain Division and World War II veteran who made lasting contributions to the Fort Drum community.

Morrell was born on Jan. 14, 1924, in Manchester, New Hampshire. He became an avid skier in his youth, joining the first ski class at the Hannes Schneider Ski School at Cranmore Mountain.

Schneider, an Austrian ski instructor and World War I veteran, helped popularize skiing in America. His New Hampshire school would become famous for his skiing methods, and many of his students became prominent skiers and instructors.

Benno Rybizka, considered to be a pioneer of American skiing and elected to the National Ski Hall of Fame in 1991, also taught at the ski school.

After certifying as a professional ski instructor, Morrell enlisted in the Army, and he joined the new mountain and ski troops being formed at Camp Hale, Colorado. Schnieder and Rybizka furnished letters of recommendation that were required for this specialized unit.

“During World War II, everybody that did any skiing knew that the 10th Mountain Division was being formed, so we all wanted to join it,” Morrell said during a 2004 oral interview.

He enlisted on Jan. 13, 1943, at the age of 19. First assigned as a rifleman with Company C, 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment, Morrell’s skills on the slopes made him more valuable serving in the 10th Reconnaissance Troop as a ski instructor. All the advanced skiers and climbers were detailed to this unit to provide Soldiers with ski and mountaineering lessons.

Morrell said that the inherent uniqueness of being in the new mountain troops was a source of pride for everyone.

“We had good publicity, and they called us ski troopers, and they even made a movie at Camp Hale,” he said. “We knew we were special.”

Morrell said one of the highlights of his time in training was an experimental cross-country excursion in February 1944. As reported in the Camp Hale Skizette, it was “one of the most ambitious ski marches ever attempted by mountain troopers” at the Army post.

Morrell was among a group of 30 Soldiers to hike roughly 50 miles to Aspen through high mountains and narrow valleys, covered in deep snow.

“We started out from Cooper Hill at 10,400 feet,” he said. “We went probably down to about 10,000 feet as we crossed the valley. And the Continental Divide runs pretty close to 12,000 feet. We tried to pick the saddles …. get over 12,000, maybe 13,000 feet.”

They carried heavy rucksacks, avalanche probes, rope, ski axes and rations. Throughout the four-day trip, they shared trail-breaking duties so each Soldier practiced route selection. At times, Soldiers could only lead for about 10 minutes in places where deep snow required maximum physical exertion.

“You had no trails, you had nothing,” Morrell said. “You just bushwhacked. It was a good trip because we learned a lot.”

After setting up camp one night, Morrell recalled hearing something that sounded like artillery fire.

“And then we realized it was an avalanche, and it came within less than 100 feet of us,” he said. “We thought, ‘Well, that’s the end of that. That won’t happen again.’ So, we went to bed, and in the middle of the night we heard another boom.”

Morrell said that the training at Camp Hale was tough, but Soldiers were conditioned to certain hardships having lived through the Great Depression.

“When you’ve lived through the depression years, some of the fellows that came into the Army at that time had never known a new pair of shoes,” Morrell said. “So, we were all tuned in to making do with what you had. For most of us, the Army was a pretty good deal. Plenty of food – I gained 20 pounds in the first three months. You toughened right up, and you felt good.”

During the infamous divisional series (D-Series) training event, Morrell said he participated as part of the opposition force.

“I was the enemy,” he said. “We got to sleep most nights in the barracks. We’d go out on patrol and harass the troops and then disappear.”

Although not as proficient in rock climbing, Morrell joined a group of professional mountaineers in the Mountain Training Group where he learned from fellow Soldiers like Paul Petzoldt. Petzoldt made his first ascent of the Grand Teton at age 16, and he was a member of the first American team to attempt a climb on K2 – the world’s second highest peak.

“I was fortunate because rock climbing … you could get killed pretty easy,” Morrell said. “But we had such excellent instructors and experienced mountaineers there that safety was always utmost in our mind. So even though we got in tight spots, we’d get out of them because everybody worked together.”

In the spring of 1944, the MTG instructors left Camp Hale to teach Soldiers from other divisions on mountain survival skills at Seneca Rocks in Elkins, West Virginia. When they learned about the launch of D-Day on June 6, Morrell said they were eager to return to their units and await deployment orders. However, the division had already left for Camp Swift, Texas, and upon his arrival Morrell was assigned as a muleskinner.

Morale was low at their new camp. Many Soldiers who had trained nonstop for two years in the snow, freezing temperatures, and high altitude, now had to acclimate to ruck marches in the blistering Texas heat.

In “The Winter Army,” by Maurice Isserman, Morrell’s climbing buddy Paul Petzold experienced a sneak attack when a snake dropped from a tree into his foxhole. The next day, Petzold arranged for a transfer to Fort Benning where he served as an instructor for the duration of the war.

“Everybody wanted out of the division,” Morrell said. “We weren’t a flatlander outfit. It was too hot; we didn’t like it. But the moment that we knew we were going to Italy, it changed right around, 180 degrees. And then you didn’t hear anybody wanting to get out. They just said, ‘When do we go?’”

Morrell deployed on Christmas Day with the 10th Medical Battalion, and served as a section sergeant with Company A, 10th Medical Battalion. As part of a litter team, Morrell would move onto the battlefield to retrieve wounded Soldiers and rush them to the aid station.

“We didn’t have any weapons, we had no defense except the red cross you had on your helmet,” Morrell said. “And you’d hope the Germans would respect that. Sometimes they did, sometimes they didn’t.”

Being in the line of fire so often, Morrell said there wasn’t a fear of being shot as much as the threat of getting hit by artillery or mortar rounds.

“If you’re anywhere near the front, you’re going to be around incoming (fire),” he said. “Company A of the 10th Mountain Medical Battalion had no one killed. But we had as many Purple Hearts as any other unit.”

Morrell received his Purple Heart after being wounded in the foot when a mortar exploded outside a building where the casualties were treated. After seeing a shell fragment rip into his colleague’s hip, Morrell said he felt lucky his own injury wasn’t severe.

“And I didn’t dare take my boot off for fear I couldn’t get it back on again,” he said. “I could walk on it (but) it hurt.”

Morrell earned a direct commission as a second lieutenant before the end of the war. After Germany surrendered in Italy, the 10th Mountain Division transitioned to a peacekeeping mission at the Yugoslavian border, near Trieste. Morrell said he was put in charge of recreation for the troops, and he organized weekly parties. His service in the 10th Mountain Division ended when the division was deactivated on Nov. 30, 1945.

Morrell said that the 10th Mountain Division didn’t win the war in Italy, as some of his comrades liked to say, but they played a significant role, nonetheless.

“We took Mount Belvedere, which then allowed us to go down, advance further, and get ready for the invasion of Po Valley,” he said. “Our job was to be Mountain Soldiers. Where other divisions had trouble, we didn’t. We took it, held it, and then kept on going.”

Morrell remained in the Army Reserve and was recalled to active duty in September 1950 during the Korean War. He served in the 24th Infantry Division Artillery Medial Detachment and later commanded the ambulance company.

Morrell witnessed some of the heaviest fighting in the war as the 24th Infantry Division retook Seoul and pushed through to the 38th Parallel where they faced repeated counterattacks.

In 1952, Morrell returned home to New Hampshire, and to civilian life once again. For his service in both wars, he was awarded three Bronze Star medals, the Purple Heart, the European Theater Service Medal, the Korean Conflict Service Medal, and twice awarded the Combat Medical Badge.

After being discharged from the Army, Morrell worked as a carpenter and cabinet maker in New Hampshire. He spent most of his professional life as a sales engineer in the paper and sawmill industry. In 1967, he moved to northern New York where he helped establish one of the state’s first recycling plants.

The 10th Mountain Division reactivated on Feb. 13, 1985, and made Fort Drum its home. As a member of the National Association of the 10th Mountain Division, Morrell was appointed as the division liaison officer.

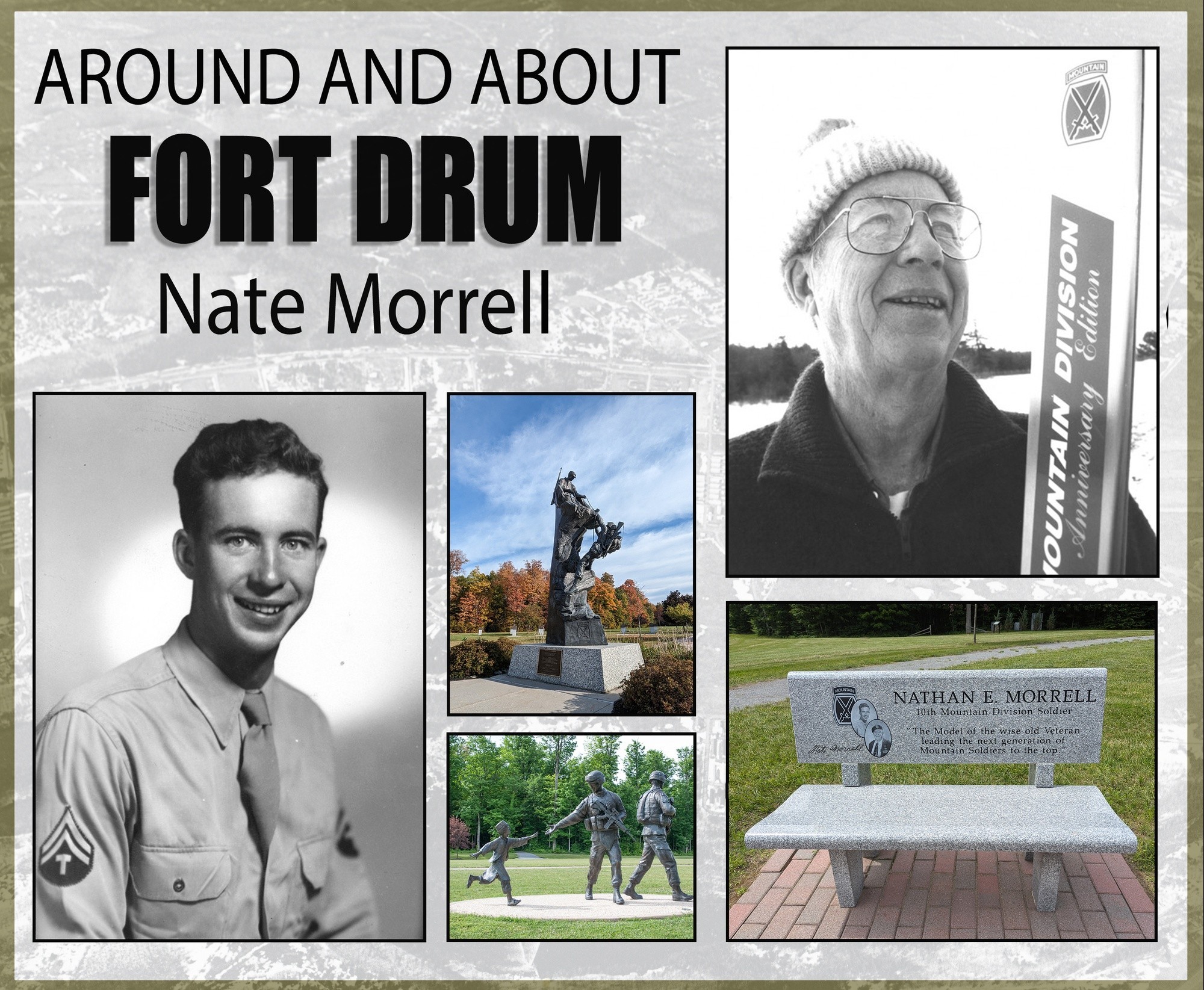

The organization commissioned the Military Mountaineers Monument, which was created by sculptress Susan Grant Raymond and dedicated on post in 1991. In 1997, this monument became the centerpiece for the new Memorial Park across from Hays Hall, the division headquarters building.

In 1998, Morrell was named president of the National Association of the 10th Mountain Division, and he served in that capacity for four years until becoming chairman of the board.

Following the events of 9/11, elements of the 10th Mountain Division (LI) deployed to Afghanistan, and later to Iraq, in support of the war on terrorism. Morrell wanted to honor their service and sacrifice with a new monument in Memorial Park.

In 2005, Morrell established Project Fallen Warrior Monument with permission from the 10th Mountain Division (LI) commander at the time, Maj. Gen. Lloyd Austin. He worked with Raymond to develop the design for a two-piece monument that honors the fallen and symbolizes hope for the future.

Ultimately, it was a Department of the Army award to the Fort Drum garrison that helped fund the Fallen Warrior Monument. A groundbreaking ceremony was conducted on Oct. 5, 2012.

Morrell died on March 6, 2013, at the age of 89, after a brief hospitalization in Watertown. The 10th Mountain Division (LI) held a memorial ceremony to honor Morrell at the North Riva Ridge Chapel on March 9, 2013. During the event, speakers described Morrell as a “cheerful and larger-than-life personality” who was passionate about the well-being of 10th Mountain Division (LI) Soldiers and families.

On Oct. 29, 2013, Fort Drum community members gathered in Memorial Park for the unveiling of the Fallen Warrior Monument. Raymond attended the ceremony, as well as Morrell’s daughter Jennifer.

The bench honoring Morrell was installed in Memorial Park on June 18, 2019, one day before the Annual Remembrance Ceremony.

(Editor’s Note: This article was written with source material from the Fort Drum Public Affairs newspaper archive, an oral history courtesy of the Denver Public Library’s Special Collections and Archives, and “Mountain Troops and Medics,” by Albert Meinke. Additional photos provided by Jeff Fox)

Social Sharing