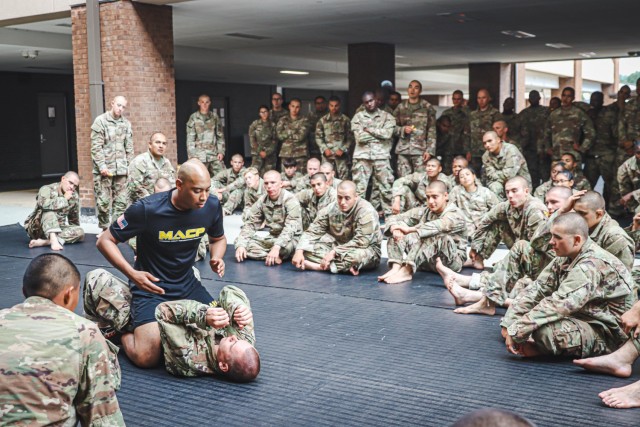

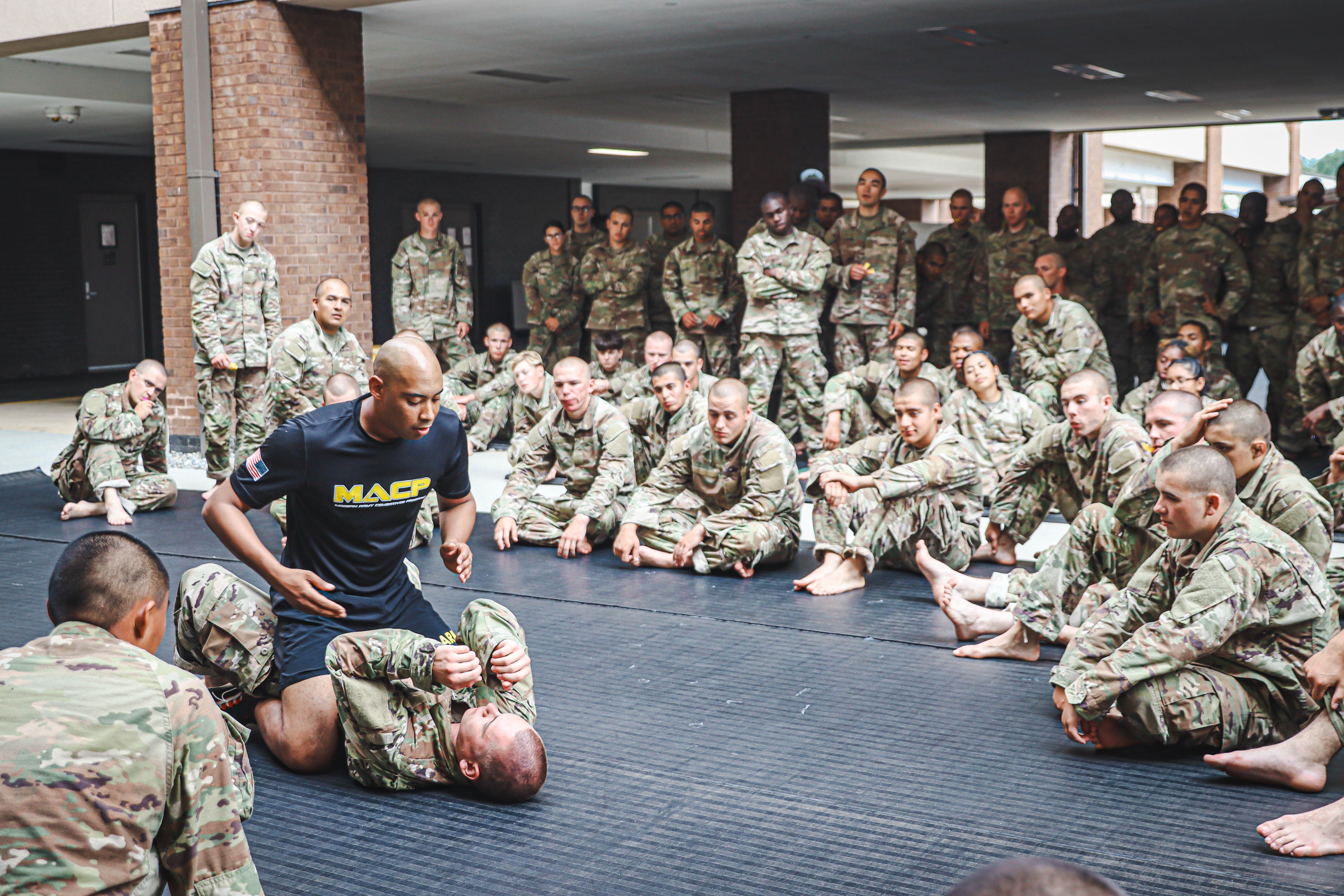

Combatives training is a valuable tool for U.S. Army commanders because it improves unit cohesion and lethality. I believe hand-to-hand combat will also prove consequential in future armed conflict. All units should incorporate combatives into training and send Soldiers to the Basic and Tactical Combatives Courses (BCC and TCC, respectively). Service members know combatives as it is defined by Training Circular (TC) 3-22.150: “the art of hand-to-hand combat.” As both a former collegiate wrestler and an active-duty Army officer with experience in armored and special operations units, I have a passion for ensuring all service members receive regular combatives instruction.

As a disclaimer, I acknowledge that every unit in the Army is busy, and the last thing many commanders and junior leaders are looking for is someone telling them about something more they should start doing. Nonetheless, here I am telling you… you need to be training on combatives. When done right, this training is a force multiplier that will improve unit culture and build more cohesive teams. And more importantly, a fighting Army must be composed of fighting Soldiers; anything less is a lack of preparation for the next conflict.

Relevance of Combatives: In Practicality and for the Warrior Ethos

The sell for combatives is twofold. First is the obvious need for Soldiers to have the technical ability, will, and confidence to engage in a hand-to-hand exchange with an enemy combatant. Second is the not-so-obvious — but still crucial — contribution of combatives training towards developing Warrior Ethos and unit cohesion.

In a landscape of increasingly competitive peer threats, do we want to be the Army that shifts focus away from hand-to-hand combat? As MSG Colton Smith — a U.S. Army Soldier, former The Ultimate Fighter champion, and UFC fighter — said, “The Russians are doing sambo. What are we doing?”1 Army Special Forces LTC (Retired) Jason Abbott echoed MSG Smith’s concerns: “Many of our global competitors have a standardized martial arts program within their combat arms. It’s a requirement. Russia and China both have formidable and robust martial arts training.”2 While our Army does in fact have a respectable combatives program, peer threats and the future of large-scale combat operations (LSCO) demand more. The problem does not lie in the schoolhouse, but rather the onus is on warfighters throughout the force serving in operational units.

It is tempting to assert that given the increasing range and availability of direct fire weapons and advances in cyber warfare and unmanned aerial systems (UAS), to name just a few, the last skill we need to spend time on is combatives. Recent history suggests this is not the case. In his article “The Point of the Bayonet,” John Stone wrote that it is the infantry’s job to “finish proceedings as rapidly as possible… the most lethal weapons can be surprisingly ineffective against a well-concealed and protected enemy.”3 This was especially true during the global war on terrorism (GWOT), where Soldiers were required to seek out and kill a well-concealed enemy knowledgeable of his “home turf.”

As I write this, there are more current examples of hand-to-hand fighting in conflicts around the world. Recent Sino-Indian border tension has led to skirmishes where soldiers are being killed without any shots fired.4 In March 2023, Russian and Ukrainian troops fought in trenches with shovels and fists.5 As of January 2024, Israeli special forces were forced to resort to fighting Hamas’s guerrilla-like tactics “hand to hand” and “chest to chest” in tunnels.6 Despite some forces having massive advantages above ground, history tends to show that a capable enemy will find ways to level the playing field. Similarly, underground tunnels may take away nearly all a modern army’s advantages, not dissimilar to the Vietcong’s use of tunnels more than a half century ago. To stress the necessity of hand-to-hand combat in LSCO, MSG Smith simply stated, “When you take away our ‘tools,’ we are left with our hands.”7 He stressed the importance of skillfully continuing a fight when our primary weapons are taken away.

Abbott has a unique perspective on the utility of combatives due to his special operations forces (SOF) experience while deployed to semi-permissive (or even permissive) environments. “A large number of SOF deployments are Theater Security Cooperation Programs (TSCP) or Joint Combined Exchange Training (JCET),” he said. “These are generally extended TDY [temporary duty] trips to different countries to train and engage with partner forces... Business casual, daily dress, or business suits are the norm.” He pointed to these circumstances as key to a Soldier’s ability to navigate the “aggress vs. digress” dichotomy and states that Soldiers must have the ability to control hostile environments (though not necessarily while in official combat zones) by using a “pivot point.” This “pivot point” enables the Soldier to either:

- Continue a fight and neutralize or destroy an attacker, or

- Create a favorable opportunity to break contact and get away.

Either one of the aforementioned scenarios requires “considerable martial arts training,” according to Abbott. Without this, combatants may find themselves out of options. For example, an untrained martial artist may be compelled to use lethal force — even when not necessary. Equally as likely though is an untrained martial artist only having the option to run away — even if a non-lethal deterrent or defense would better suit the mission.

Regarding its contributions to the Warrior Ethos, combatives is a microcosm for warfare itself. Each “roll,” round, or training session is both a test of intestinal fortitude and a strategic chess match. When conducted in accordance with TC 3-22.150, combatives directly contributes to unit cohesion. Dirk McComas, the lead civilian combatives instructor at the Maneuver Center of Excellence (MCoE) and a 17-year GWOT veteran, points out that humility is manifested in the “tap-out.”8 When one is caught in a submission, he “taps” to tell the other Soldier “stop, you won.” First, he is trusting that training partner to stop; second, he must have the humility to admit defeat. His partner also has the humility to understand that he could be the next one to tap out. Individuals who have experience with martial arts will tend to agree with MSG Smith’s assertion that combatives “is the battlefield of life.”

The Problem Statement: What We Are Missing and Why

Generally speaking, the Army may be missing opportunities to nest combatives with training plans in operational units. It is important to recognize why, less I become victim to the “Chesterton’s Fence” logical fallacy.9 As technology has improved, warfighting has morphed into a long-distance affair.10 Some of us may intuitively correlate longer ranges and newer distance-killing weapons systems with a lack of relevance for the opposite — close-distance fighting. From a surface level, this makes sense. Why would we waste time and money on tactics that some may see as archaic when we need to acquire, teach, and train on drones, Next Generation Squad Weapons, and other new technologies? This mindset is a slippery slope. Where do we draw the line? Is the Infantry itself going to become obsolete? Actually, isn’t future warfare just going to be robots anyway? Those questions sound a bit ridiculous (believe it or not, I have heard them asked before), but when they are said out loud, it makes us ponder… should we ever stop focusing on the basics? And isn’t the ability to physically fight another combatant with one’s own bare hands the most basic of all the basics?

There is no real forcing function for junior leaders to incorporate the training at their levels. It is highly commander dependent. There are no bubbles turning green to brief after commanders complete training their Soldiers to be lethal with their bare hands. The COVID-19 pandemic did not help as unit combatives centers temporarily closed and this type of training was paused.

Additionally, while the Modern Army Combatives Program (MACP) is an underutilized tool for force, it alone cannot address our lack of competency in combatives. Abbott opines, “Of all the inputs for MACP, Brazilian Jiu Jitsu is the backbone, which takes up to 10 years to earn a black belt. The length of time it takes a U.S. Soldier to gain the proper experience to train at that level, let alone teach, is far longer than the NCO Education System (NCOES) model; thus, it is never truly achieved at a rate that is efficient for both the training and delivery of the skillset.”11 I acknowledge that we should not try to create black belts through MACP; doing so would be a misallocation of time and resources.

Nonetheless, hand-to-hand fighting is a skill that deteriorates; and while sending Soldiers to the MACP is a great start, the real solution to this problem is ensuring a fighting culture in units at the tactical level. We iteratively update requirements and models for unit training management of mission-essential tasks; why would we overlook one of the most basic Soldier skills: combatives?

The How: Incorporating Combatives in your Unit

Culture is the number one contributor to the effective incorporation of combatives. The solution to many of the problems addressed here is to sustain, grow, and promote current initiatives that foster excellence in hand-to-hand fighting. The MCoE’s annual Lacerda Cup is a phenomenal event that rewards excellence in a Soldier’s ability to fight. There is an immense amount of pride in knowing that if you win there, you are the best fighter in the Army at that weight class. In my experience, this sense of accomplishment and healthy competition is present in the most elite units in our Army. Seeing command influence and promotion of this event from the MCoE over the past few years has made the entire combatives community proud. More importantly, I have seen firsthand examples of junior Soldiers who start training just to compete in future competitions; these Soldiers will then become NCOs and bring those skills back to their unit. The 75th Ranger Regiment — through their use of the Special Operations Combatives Program (SOCP) — instills this culture in all candidates during their selection process. Once they arrive at their battalion, junior Rangers then lead informal training with each other. My personal experience is that this is because junior leaders are supported in their endeavors to train combatives regularly. Perhaps this stems from the unit’s role in GWOT operations, where 19 percent of Soldiers (not just SOF) from 2004 to 2008 reported using hand-to-hand fighting.12 Most years, the regiment hosts command-sponsored combatives tournaments, culminating in the “advanced ruleset” for finals matches (a ruleset roughly equivalent to an amateur MMA fight). The 82nd Airborne Division and the 4th Infantry Division do the same during “All-American Week” and “Ivy Week,” respectively. To help build this culture throughout the entire force, MSG Smith says that leaders should send Soldiers to BCC and TCC during the unit’s red cycle. Both schools also produce promotion points for enlisted Soldiers.

Common Pitfalls

Two common reasons for commanders not promoting or supporting combatives:

1. Lack of knowledge. A lack of knowledge or higher-level focus on this skill is a common reason for the absence of combatives in some units. We all have a bias towards training what we know, and the truth of the matter is that martial arts is just less popular than other activities in today’s society.

The Solution: Reach out to the installation combatives NCOIC to schedule training with your unit. This can be done with informal training at the “fight house” on post (most installations have at least one of these facilities — fully equipped with mats and gloves, etc.) or by formally sending Soldiers to BCC (also known as Level 1 combatives). Once Soldiers are BCC qualified, they can bring that knowledge back to their battalion and exponentially increase the unit’s skill level through routine training. When in doubt, reach out to MACP personnel to ask for guidance on how to incorporate the training.13

2. Pride. This pitfall does not necessarily stem from ego, but all leaders inherently dislike being seen as incompetent among their Soldiers. We all have similar stories that resonate with us. Some of the most common are the second lieutenant getting his platoon lost on his first field training exercise (a tale as old as time), the platoon leader or executive officer trying to find the battery on his Advanced Combat Optical Gunsight (ACOG) because one of his team leaders told him to (hint: it doesn’t exist), or an officer not being able to talk on the radio because his microphone is not connected. If any of these scenarios are a fear of yours (don’t lie to yourself), then what is worse than being physically manhandled by the men and women you are in charge of? Some may see this as embarrassing, or worse — unprofessional.

The Solution: Through conducting this training at three different installations, I have seen multiple beginner-level martial artists get on the mats to train with their Soldiers. Many of them were first sergeants, captains, sergeants major, and colonels. Any potential fear they have of being professionally embarrassed is answered with respect from the Soldiers grappling with them. Just like any warrior skill, an important first step is the willingness to learn, and the Soldiers see that. Generally, of the leaders who attend combatives training, the least experienced garner the most respect from the Soldiers there. Training how to fight with Soldiers does not erode trust, it builds trust.

In closing, the onus falls on junior leaders to communicate the value of combatives to their bosses: Combatives is an easily resourced team-building activity that will prove crucial to our lethality in the next armed conflict. While the maximum effective range of the M4 carbine is 500 meters, Soldiers in the 21st century still need to be able to engage the enemy at a range of 0 meters.

Notes

1 MSG Colton Smith, personal interview with author, April 2024.

2 LTC (Retired) Jason Abbott, personal interview with author, July 2024.

3 John Stone, “The Point of the Bayonet,” Technology and Culture 53/4 (October 2012), https://www.jstor.org/stable/41682745.

4 BBC News, “India-China Clash: 20 Indian Troops Killed in Ladakh Fighting,” 16 June 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-53061476.

5 VOA News, “Russia-Ukraine Fighting Devolves into Hand-to-Hand Combat,” 5 March 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/russia-ukraine-fighting-devolves-into-hand-to-hand-combat-/6990568.html.

6 Anshel Pfeffer, “The Gaza War Goes Deep Underground,” The Jewish Chronicle, 11 January 2024, https://www.thejc.com/lets-talk/analysis/the-gaza-war-goes-deep-underground-k2e6btpf.

7 MSG Smith, personal interview.

8 Dirk McComas, personal interview with author, 2024.

9 “The short version of the Fallacy of Chesterton’s Fence is this: don’t ever take down a fence until you know why it was put up.” Alexander Ooms, “Commentary: The Fallacy of Chesterton’s Fence.” Chalkbeat, 4 January 2012, www.chalkbeat.org/colorado/2012/1/4/21096855/commentary-the-fallacy-of-chesterton-s-fence/.

10 Stone, “The Point of the Bayonet.”

11 Abbott, personal interview.

12 Peter R. Jensen, “Hand-to-Hand Combat and the Use of Combatives Skills: An Analysis of United States Army Post-Combat Surveys from 2004-2008,” United States Military Academy’s Center for Enhanced Performance, November 2014, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA612103.pdf.

13 “Modern Army Combatives,” https://www.moore.army.mil/armor/316thcav/Combatives/.

CPT Norman “Buddy” Conley is currently a student at the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School. His previous assignments include serving as an operations officer, special projects officer, and platoon leader in the Ranger Special Troops Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, Fort Moore, GA; and as a platoon Leader in 1st Battalion, 66th Armor Regiment, 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, Fort Carson, CO. He represented the 75th Ranger Regiment at the 2022 Lacerda Cup (1st place in the cruiserweight division) and 2023 Best Ranger Competition (11th place).

This article appeared in the Winter 2024-2025 issue of Infantry. View this issue at https://www.moore.army.mil/Infantry/Magazine/issues/2024/Winter/

Social Sharing