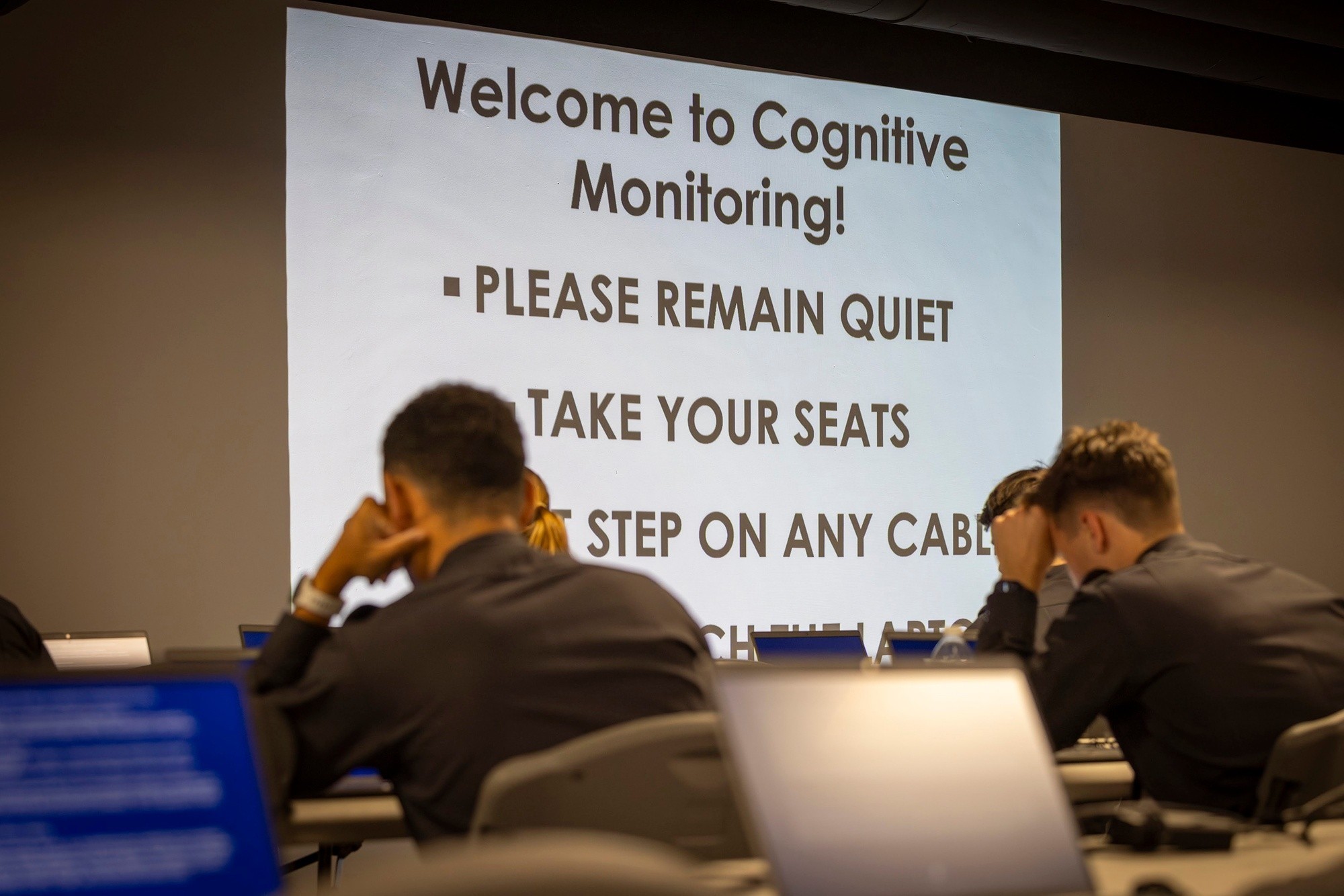

WEST POINT, N.Y. – In supporting the Department of Defense and the Army’s Warfighter Brain Health Initiative, members of the U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General (OTSG) spent two days, Nov. 4-5, testing the baseline cognitive assessments of U.S. Military Academy first-class cadets.

The cognitive assessment program, which began in 2007 primarily as a pre-deployment and injury-centric tool, is now monitoring all initial entry military members, enlisted and future officers, as a protective measure of brain health for the entirety of their military careers.

The Initial Entry Training (IET) Cognitive Monitoring Program (CMP) launched in July at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and then continued at other IET stations throughout the Army, the Marines, Navy, ROTC programs and other military academies.

Dr. Steven Porter, chief of the Neurocognitive Assessment Branch at the U.S. Army OTSG, emphasized one of the main aspects of these initial assessments in monitoring brain health of servicemembers is making sure that if they were involved in a health, brain-altering incident at any point in their careers, and it results in a cognitive change, that doctors or clinicians will have the ability to identify it early on.

“We can intervene early, which allows us to provide whatever services might be needed, even if that means just taking a knee for 24-to-48 hours because the brain will spontaneously recover,” Porter explained.

Porter said this is not a new concept since they were taking baseline assessments since 2007 at the height of the Global War on Terrorism, but the brain health initiative makes it more defined now.

“Our military members were exposed to (IED) blasts, and they were receiving concussions. The moderate and severe concussions are much more visible, but the mild concussions tend to not be visible,” Porter stated. “People were hiding them more, and unfortunately weren’t seeking care.

“The science was in its infancy then … now, should you sustain a suspected concussive injury, we give you the test immediately and then compare you to your baseline,” Porter added. “That will tell us a couple of things. One, it’ll tell us the extent of your injury, but most importantly, it’s going to help us track your recovery.”

Porter said the ramifications of a concussion, depending on severity, can lead to physiological symptoms, which include mood changes, but also balance issues and cognitive processing, which is the speed by which you process information.

“That is one of the last things that comes back to resolution without a baseline measure to know where you were before the injury,” Porter said. “Previously, it was very difficult for providers to understand when you were back (to normal) because you could be physically recovered with no dizziness, no nausea, no vomiting, no overt physical symptoms, but your processing could still not have been back to normal.”

Col. Jama VanHorne-Sealy, director of the U.S. Army Occupational Health Directorate, said overall the initiative is focused on the importance of optimizing both the physical and cognitive performance of servicemembers to enhance and maintain force readiness.

“Taking care of our Soldiers is and always will be our top priority for the Army,” VanHorne-Sealy said. “In 2007, we began conducting cognitive baseline assessments as part of a program to understand brain injury after exposure to IEDs. The assessment was part of a pre-deployment process.

“In response to increased brain health risk understanding,” she added, “the program has evolved to a cognitive monitoring program that will span the Soldier’s entire military career.”

As the Firstie cadets go through the baseline process, the intent will be to collect the cognitive baseline of each one of them early in their military career to identify any neurocognitive changes later to help any recovery monitoring they may need within a post-Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) diagnosis.

“Using the baseline data, we can compare future reassessments to determine if a medical evaluation or care is needed,” VanHorne-Sealy explained. “However, based on the Soldier’s occupational specialty (or branch) risk, they will be reassessed between one to three years throughout their career.”

Porter reiterated, whether it is in training or on deployment, dependent on MOS or branch, whomever has the highest risk of exposure to “blast overpressure” from explosions will be getting reassessments more frequently.

“We can monitor them, and if there are changes happening, we need to step in early,” Porter said.

Porter defined that baseline testing involves 10 modules of cognition, which are the 10 areas of your brain that processes information.

“How fast does your brain process information?” Porter said. “They’re (cadets) taking a test that allows us to look at the 10 domains or 10 areas of cognitive functioning to see where they are today.”

The point of the process is when they come back for a reassessment, it is to see if they are at the same cognitive level as previously tested.

“We will know through this test if your shift is greater than expected,” Porter said. “It’s a screening tool that tells us, ‘OK, we need to take a closer look.’ If so, then we do a clinical interview, clinical evaluation and additional follow up testing if it is necessary to see what might be causing that clinical change.”

As for the testing, it depends on the module, but it can involve stimulus that pops up on a computer screen and you press the mouse for your reaction time. Some of the other assessment modules include short-term memory and simple mathematical problems.

For Porter, he has been a neurocognitive clinician for 24 years, the first 20 in the Navy and then less than two years with U.S. Army Special Operations Command before his current role. He determines that his role is about getting servicemembers back in the field and being as proficient as they can.

Being proactive in the monitoring process from the start of a career is a relatively new concept, but early intervention can change the dynamic of a Soldier’s career, which will “keep them safe and meet the mission,” Porter said.

Porter considers his job with the Army OTSG an amazing experience being a part of the lead agency in cognitive monitoring to positively change the lives and careers of many Soldiers.

“It is one of the most rewarding things I have done professionally,” Porter proclaimed. “I spent 20 years in the Navy as a neuropsychologist, and was involved and spearheaded the development of the new tests we use today. Overall, knowing that we can help our servicemembers earlier, it makes the 60-hour work week all the more worth it.”

Social Sharing