Journal of Seargent Hampden S. Gardiner, 1881-1883. “November 17, 1882. Have been having an extraordinary disturbance of magnetic needle for some hours past. This morning about 5 am, when coming out of the magnetic observatory after making my observation, I was suddenly dazzled by the display of light which greeted my eyes as I emerged from the darkness. The transition was so great and so sudden that I think it must have been a half minute at least before I recovered myself sufficiently to think what had happened. The whole heavens seemed one mas of colored flames arranged and disarranged and rearranged every instant… The display was so close to the earth that we repeatedly put up our hands as though we could touch something material by so doing… This display sustained its greatest grandeur for probably 10 minutes and then gradually grew less brilliant. It continued all day with occasional vivid flashes. I doubt not that this is the grandest exhibition of the aurora which has ever been witnessed. I have read descriptions of other great auroras, but they would but poorly suffice for the display I have just recorded, and which I think it would be impossible to describe adequately.”

“August 1st, 1883. Today we end our series of magnetic observations and every one heartily glad of it. We have been very fortunate with them and I think can congratulate ourselves on having as good a set as will have been taken anywhere in the Arctic region. Every body now have their affairs in such a condition that the station might be abandoned at any time.”

On August 1, 1884, a year after the penultimate entry in Seargent Hampden S. Gardiner's first journal recording his reflections on the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition and the decision to cease operations at Fort Conger and set out towards a new landscape where the crew hoped a rescue would be forthcoming, a vessel pulled into the harbor of Portsmouth, New Hampshire carrying First Lieutenant Adolphus Greely and the five other remaining survivors of the expedition, Sergeants E. L. Brainard, Julius Frederick, and Francis Long, Hospital Steward Henry Biederbeck, and Private Maurice Connell. Seargent Gardiner had died on June 12, 1884, from starvation, just 10 days before the rescue vessels finally made it to the Cape Sabine camp. A seventh rescued man, Seargent Ellis, died on July 8th on the rescue ship Neptune.

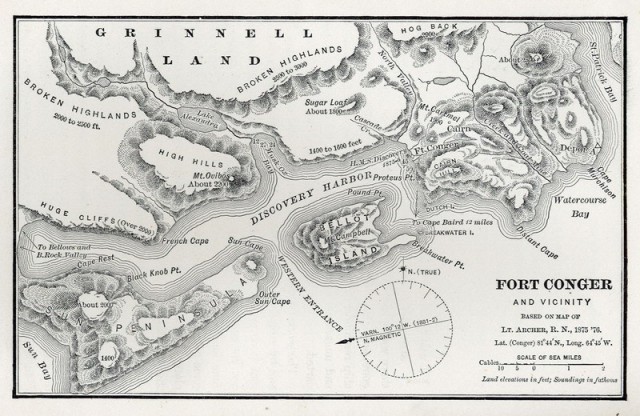

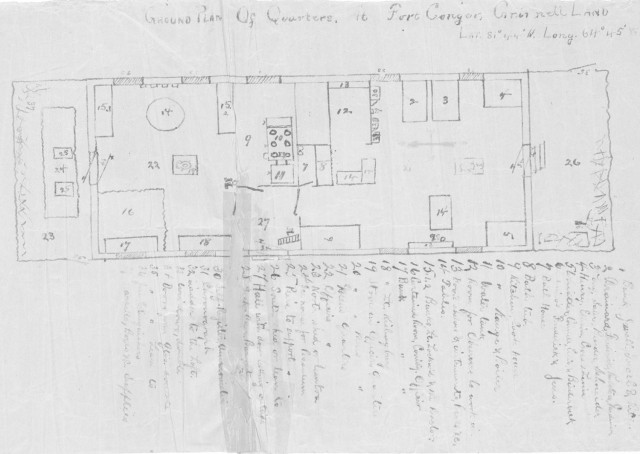

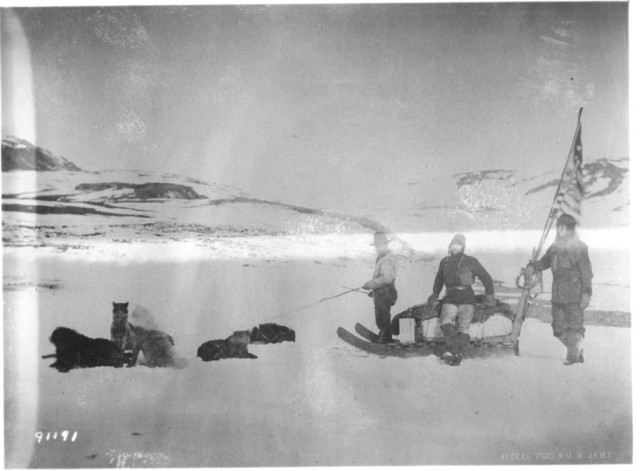

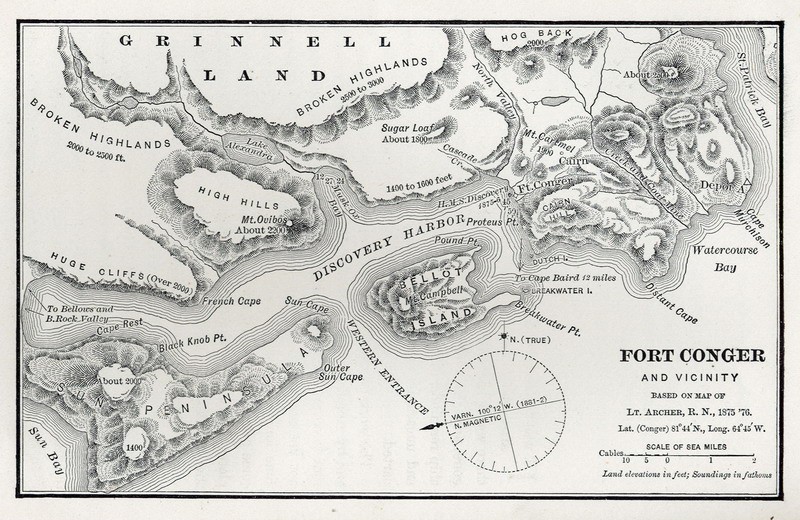

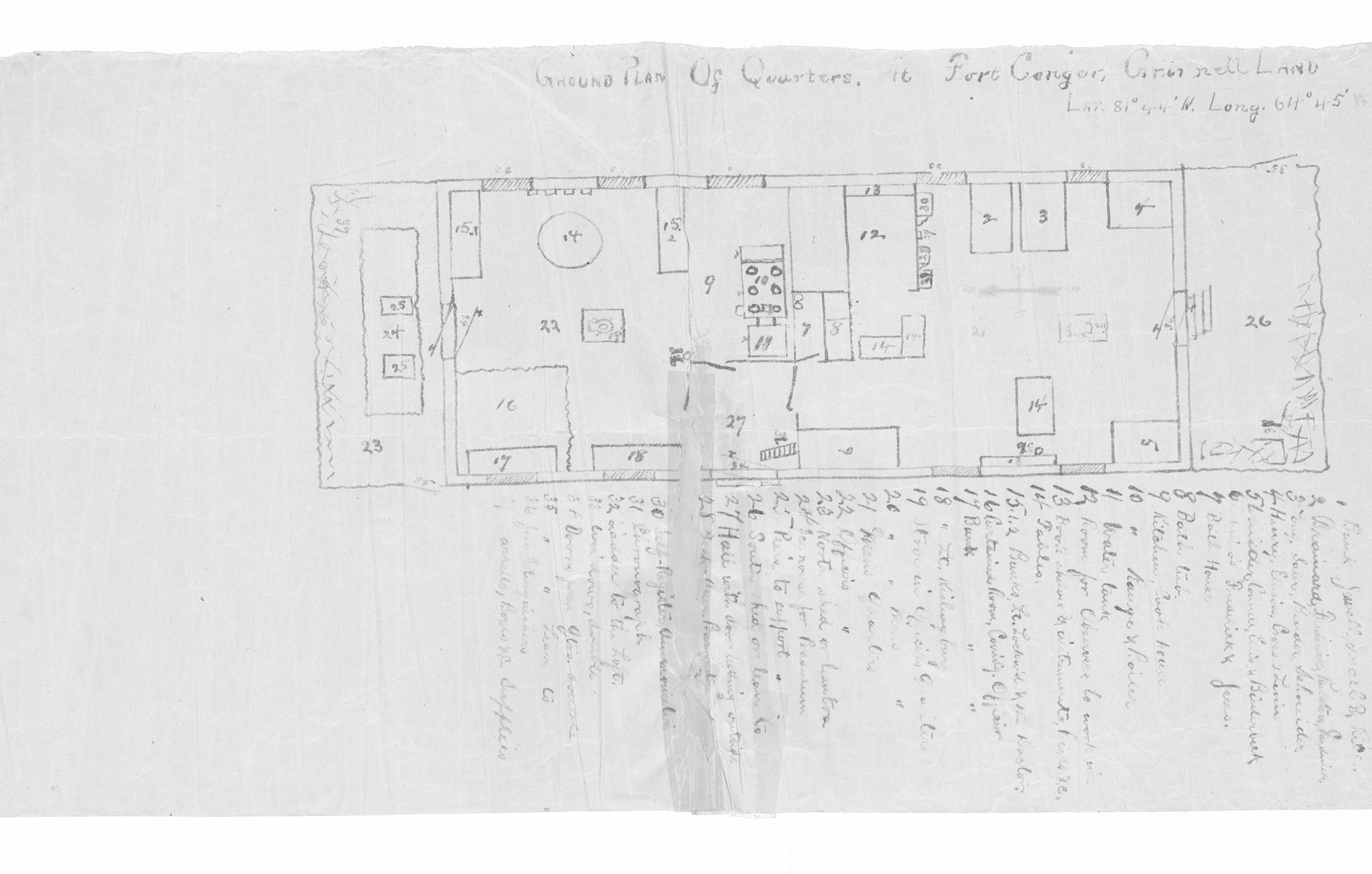

Three years earlier, 25 men had set sail for the far North under the auspices of a Signal Corps-led mission as part of the International Polar Year, where the United States planned to collect a wealth of scientific data about the Arctic and reach a new frontier. In 1881, 11 nations, including the United States, collaborated on an international program of Arctic exploration and observation of polar phenomena. The program called for the establishment of a series of circumpolar stations. These stations were used as base camps for further exploration and observation. The United States was responsible for two of these stations - one in Alaska and the other in northern Greenland. The Chief Signal Officer, General Hazen, was responsible for the two American expeditions. First Lieutenant Adolphus Greely, Fifth Cavalry (Detailed Acting Signal Officer) was placed in charge of the Greenland expedition, meant to establish a permanent station for collecting scientific data. Five weeks after departing from St. John's, Newfoundland aboard the U.S.S. Proteus, Greely and his team reached Ellesmere Island in the Arctic Circle and prepared for their unprecedented mission. Left there with 350 tons of supplies, the team moved to their chosen location and went to work building an outpost they named Fort Conger, their base for further explorations and daily observations. Planned restocking missions were expected to bolster the station in 1882 and 1883. There were contingency plans in place. If the 1882 mission did not reach Fort Conger, the party was directed to abandon the station by September 1, 1883, and follow the eastern shore of Grinnell Land (Ellesmere Island) to meet the next relief mission enroute or at Littleton Island. The 1883 relief was directed to remain in Smith Sound for as long as it could without becoming beset by ice, cache supplies, and leave men to winter if necessary to meet the expedition party. These plans failed to account for the treacherous, icy waters that would thwart the efforts to reach the Fort Conger party in either year, dooming the men to suffering and tragedy.

Gardiner's journals, which survive in the archive of the CECOM History Office, document the continuation of their scientific mission through 1883, highlighting the men's dedication to the scientific process. The U.S. Signal Corps base at Fort Conger was one of 14 international stations established in concert with 11 other nations for simultaneous scientific observations. The groups conducted over two years of scientific and geographic work, including exploring over 6000 square miles of new land reaching the most northerly point ever explored to date.

After two years when expected restocking/rescue ships failed to pass through the icy waters that captured and crushed the vessels, the crew moved closer to the promised site of relief. They came across the small cache of supplies left by the few crew members from the Proteus who ventured to the planned rescue site from the crushed ship to leave a message that further rescue attempts would be made. Settling into a small stone hut insulated with snow, the complete crew was put on reduced rations, attempting to make approximately two months' worth of relief supplies last until rescue – anticipated for almost nine months in the future. Their location was not well populated with either plant or animal life, so their rations were supplemented only rarely with small additions from hunting, such as an occasional fox or seal while ensuring that the full records of scientific work and field exploration, along with their instruments, were placed for safety and easy future discovery. The cache of records and instruments was the first thing seen by the relieving group the following year. Scientific observations of wind and weather, of temperature and pressure, continued during the day, though night measurements were abandoned. The last observation was made 40 hours before the rescue after 18 men had died.

Greely's rescue made him a well-known figure, with newspapers and magazines widely telling the story of the expedition, but not without controversy as stories of their hardships lead to rumors of cannibalism. He would go on to serve as Chief Signal Officer beginning in 1887 as a Brigadier General and was promoted to Major General in 1906. As Signal chief, he was responsible for creating and maintaining the worldwide communications networks required during and after the Spanish-American. In April 1906, he was assigned to command relief efforts following the San Francisco Earthquake. The efforts at Fort Conger continue to have implications in the study of global warming, and Greely's experiences there influenced his role as leader and scientific adopter. Greely's innovations as Chief Signal Officer led to the Army's fielding of wireless telegraphy, airplanes, motorized automobiles and trucks, and other modern equipment. He was recognized by the Medal of Honor bestowed in 1935, a few months before his death, for a life of "splendid public service."

Social Sharing