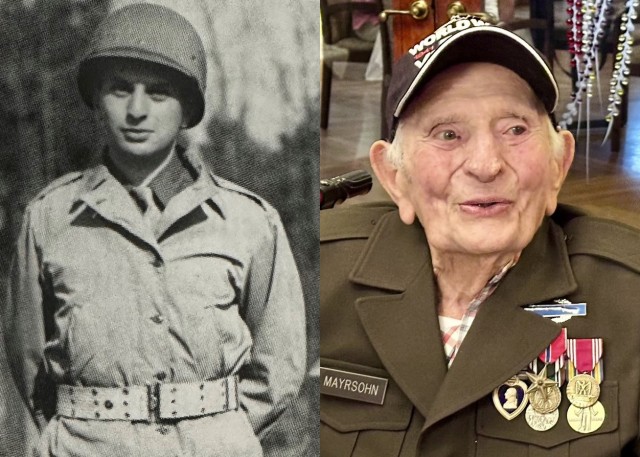

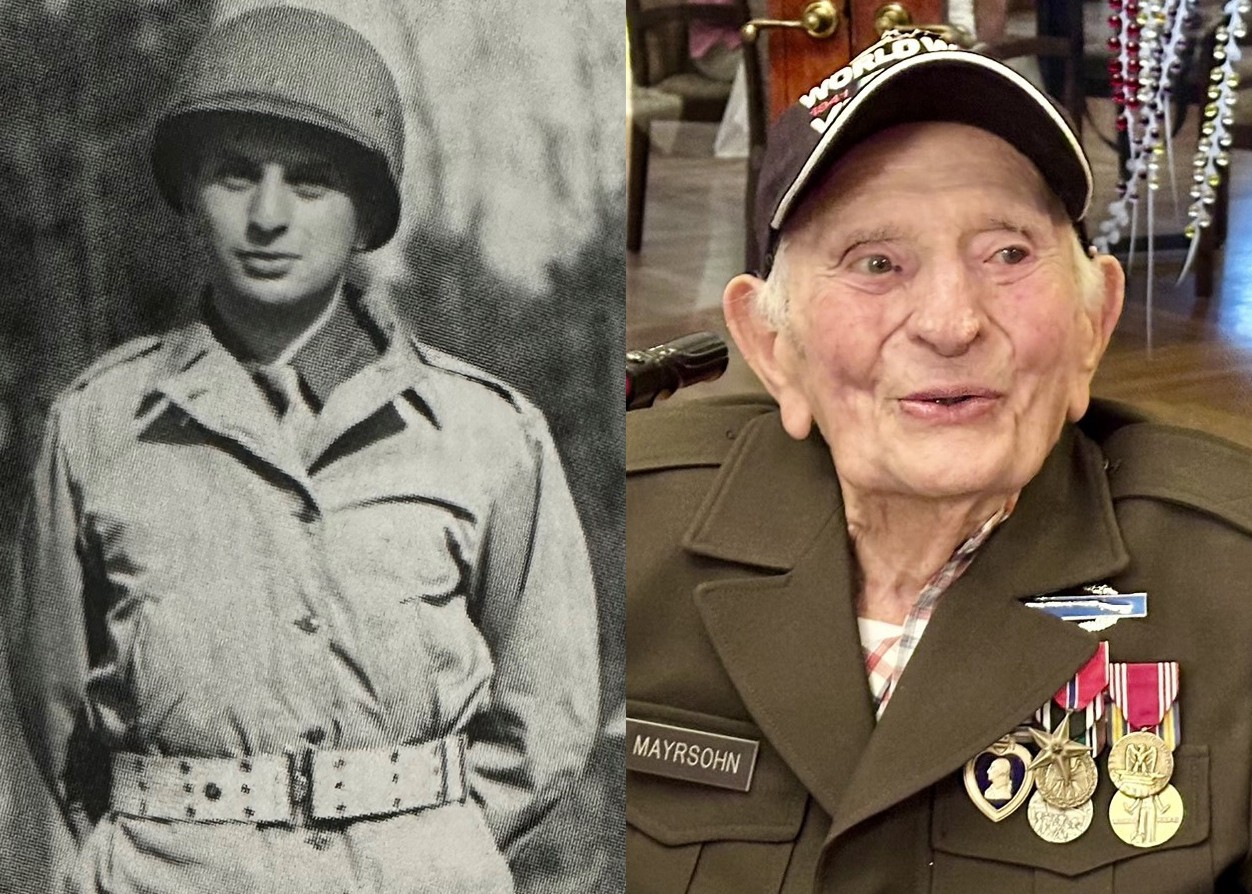

MIAMI — At 101, Army veteran Bernard “Barney” Mayrsohn considers himself a lucky man.

He has his health, his 77-year-old son, Mark, living nearby, and a comfortable home overlooking Miami’s Bay of Biscayne.

However, he was never luckier than in December 1944 when German troops overran the 106th Infantry Division at the start of the Battle of the Bulge. He would survive those first few days of terrible fighting and, five months later, walk out of a German POW camp.

While forever grateful for having survived, Mayrsohn was always bothered by losing his brown, wool “Eisenhower” or “Ike” jacket to the enemy. Poorly clothed German soldiers, without sufficient cold-weather gear themselves, stripped American POWs of their clothing, including Mayrsohn’s Ike jacket.

With a smile and watery eyes, the centenarian accepted a replacement for the jacket he lost 80 years ago from Lt. Gen. Donna Martin, the Army’s 67th inspector general, on his 101st birthday. To show her appreciation, Martin flew to Miami for the birthday celebration and to honor Mayrsohn for his service after his son Mark sent an invitation to Army senior leadership. Martin jumped at the opportunity to share in this momentous occasion.

“We are so grateful to you and the Soldiers of the 106th for the fierce resolve you showed in that first week of the battle,” Martin said, “and we know you always regretted losing your jacket.”

With that, Martin presented him with the new version of the Ike jacket, which is part of the current Army Green Service Uniform. Mayrsohn was deeply touched as Martin draped the jacket across him.

“You’ll see that the new version is cut and tailored like the original,” said Martin. “It’s got the medals you earned back then, your two Purple Hearts, the Bronze Star and the Combat Infantryman Badge. It’ll look very handsome on you.”

Bernard Mayrsohn, a former U.S. Army Private 1st Class assigned to the 106th Infantry Division during World War II, sings The Army Song with Lt. Gen. Donna W. Martin, the Inspector General, during a celebration of his 101st birthday on June 14, 2024, in Miami, Florida. Mayrsohn wears an “Ike”-style Army Green Service Uniform jacket, complete with rank insignia and medals, presented to him by Martin, The Inspector general. Mayrsohn, a veteran of the 106th Infantry Division, fought at the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, earning a Purple Heart, and spent several months as a prisoner of war in Germany. (U.S. Army photo by Lt. Col. Danielle Champagne)

After champagne and cake, Mayrsohn and Martin sang a duet of the Army Song, with the lyrics from his era, and the veteran’s voice boomed every time they sang “… the caissons go rolling along!” A quieter rendition of God Bless America followed. Martin also brought him three congratulatory letters and coins from Army Secretary Christine Wormuth, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Randy George and Director of the Army Staff Lt. Gen. Laura Potter.

Mayrsohn’s life story was captured in a 2018 biography, “From Brooklyn to the Battle of the Bulge and on to Building an International Business: The Incredible Story of Bernard (Barney) Mayrsohn.” The book recounted the heroism of the 106th ID, known as “The Golden Lions,” at the tip of the Bulge from Dec. 16, 1944, the day the battle started, until two regiments of the division were forced to surrender on Dec. 19.

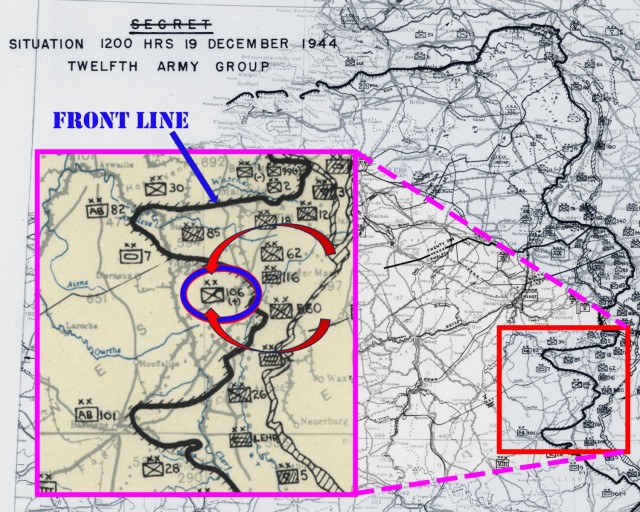

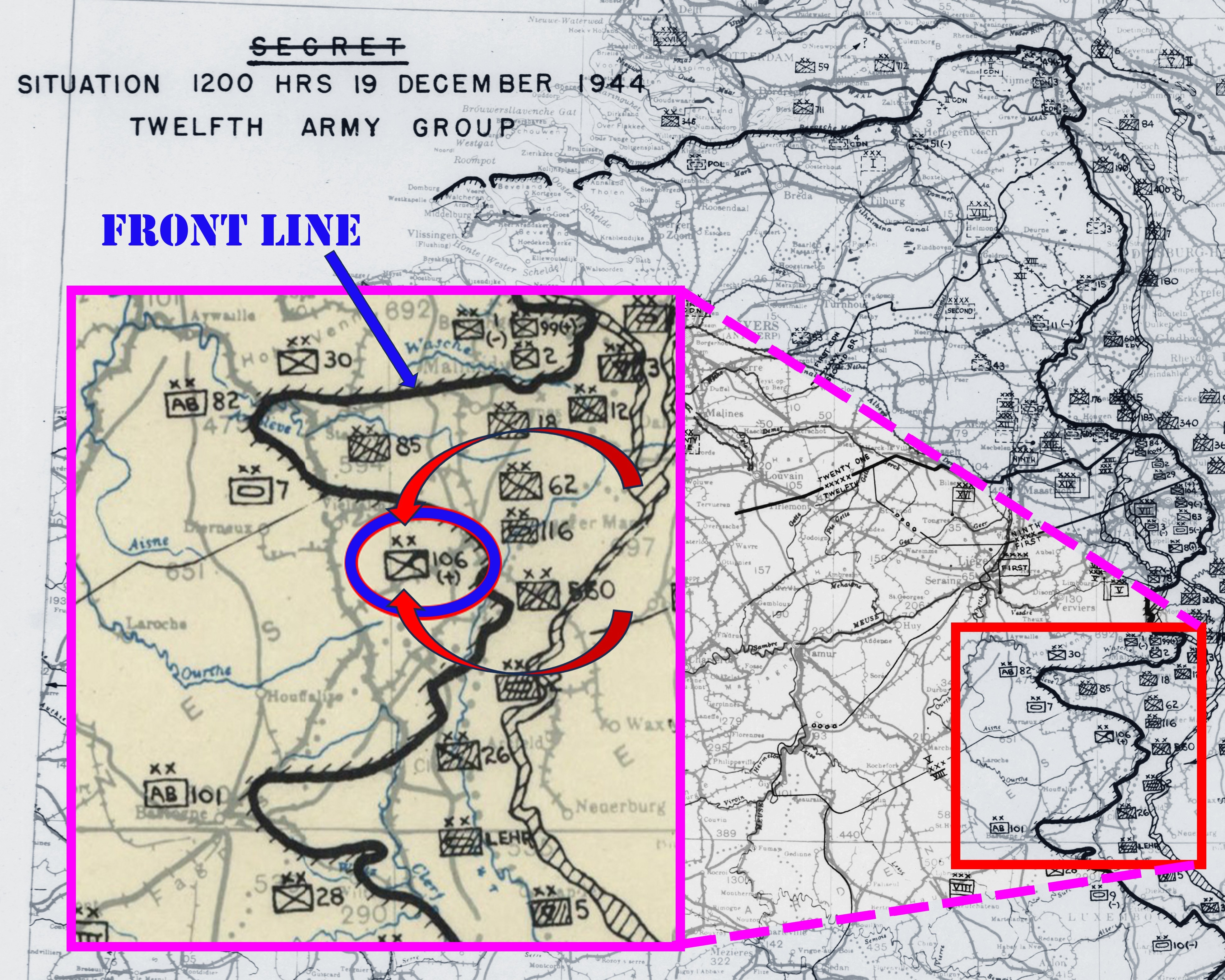

As Mayrsohn described in a 2014 video interview shot for the 70th anniversary of the battle, the 106th ID was inauspiciously positioned.

The Battle of the Bulge was one of the bloodiest battles of World War II. It signaled the end of the war and peace among countries. Seventy years later, many veterans have returned to the very land that claimed the lives of their comrades. Here is the story of the battle told through their eyes. Includes sound bites from Bernard Mayrsohn, 2nd Platoon of Cannon Company, 423rd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division. Also available in high definition.

“My 106th Division was put on the very tip… of the bulge,” he said, referring to the large pocket the Germans created in the Allied lines.

He belonged to Cannon Company, 423rd Infantry Regiment, made up mostly of Soldiers with little or no combat experience. The company took up its position on Dec. 12, seven miles from the Siegfried line in a sector known to be so quiet that GIs called it the “Ghost Front.” As Cannon Company took up their position, the outgoing troops they relieved assured them it was a chance to calmly acclimate to a position close to the enemy. Because of a “bum shoulder,” as Mayrsohn put it, he was originally rejected for service, “but I sneaked in anyway.” Due to his shoulder, his job was to run communication lines to the company’s outposts, rather than take up a rifle position.

“We were told by them [the troops they relieved], ‘Quiet front, no activity, you’re gonna get comfortable being in the front lines,’ and this was about three or four days before the Germans attacked,” he said. “We hardly got comfortable where we were set up. … On the very first morning of December 16, we all heard heavy shelling, and they all said, ‘Barney, what the hell’s happening?’ and I said ‘Well, you heard, it’s our own artillery playing games.’”

“Well, when the shelling stopped at daybreak, we saw German troops coming over to our area … and we started shooting at them,” he continued. “I think I got a couple, we shot a couple, we captured a couple. This is December 16.”

Mayrsohn recalled that German panzers went around either side of his unit’s fortifications, which meant “…in the first 24 hours we were 20 miles behind the German lines.”

Back at the house where Cannon Company headquarters was set up, Capt. James Manning, the company commander, said they were cut off and would have to fight their way out. Manning was shot and killed minutes later when he was the first to step out of the building. On a return trip to that area in 2014, Mayrsohn and Mark laid a wreath on Manning’s grave at the Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery and Memorial in eastern Belgium.

Terrible fighting continued day and night from Dec. 16-19, including hand-to-hand combat and desperate firefights, with little to no cover, to hold off the German troops. Cut off from the Army’s rear position, they had to create foxholes by throwing grenades onto frozen soil.

“For four days, our company, together with other surrounded and blocked-off companies, tried to get together with our regiment,” Mayrsohn said.

During those four days the remaining members of his unit, as well as the other units they joined with, ran out of food and ammunition while constantly surrounded and targeted by German tanks.

“We fought the 16th, 17th, the 18th,” he said. “We finally got together with our division on the 19th – what was left of the division. We were all dug in, surrounded by German tanks.”

Amid increasingly heavy casualties, surrounded and with no defenses, and under deafening fire from German tanks, the order to surrender came.

“Luckily, our smart colonel, [Charles C. Cavender] was his name, surrendered what was left of us. …His orders were, ‘Destroy your weapons and put your arms up.’”

The tragedy of combat was seared into Mayrsohn at 21 years of age.

“I was in my foxhole, shells were blowing up boys all around me. Pieces of the boys were flying all around me. We had no defense.”

Mayrsohn suffered wounds to his hand and arm, earning him the Purple Heart. After the surrender, the prisoners were marched for three days in the snow and bitter temperatures. His buddy, Hal Taylor, marched barefoot after the German troops took his shoes. Taylor developed pneumonia and Mayrsohn carried him multiple times.

When Mayrsohn and Taylor reached the German railway lines, they were crowded into cattle cars with 100 other men, although, as Mayrsohn recollected, they were intended to hold only 40, “…which was a heaven, because it was better than the snow, but it turned out not to be heaven.”

When the weather cleared, the American pilots’ mission was to destroy the German rail system. Mayrsohn recalled that U.S. aircraft strafed the trains, hitting a train ahead of his filled with American officers.

The humanity veterans show with their stories — a symbol of their strength — often comes in the form of humor, and Mayrsohn is no different. When he arrived at the Stalag IV-B prison camp near Mühlberg, he was allowed to pick out a sergeant’s coat from a huge pile of clothes.

“So, overnight I became from a private to a sergeant, and spent the rest of [the time at] the prison camp as a sergeant. That’s my story,” he said during the 2014 interview. In May 1945, Soviet troops freed the Americans.

Toward the end of the birthday celebration, Martin lingered to chat more with Mayrsohn and his son in the sunny, wood-paneled private room at the restaurant.

“It was hard to say goodbye,” she said.

After the party ended, Martin flew back to D.C., taking with her the memories of a hero of the Greatest Generation.

According to the National WWII Museum, the Army lost 19,246 Soldiers during the Battle of the Bulge and over 23,000 American troops were taken prisoner. Mayrsohn’s narrative reflects the camaraderie and bravery of so many previous generations of Soldiers, which continues to draw men and women of character into the Army to this day.

Social Sharing