A stopper or bottle closure is constructed to seal the opening of a bottle by fitting inside its neck. It prevents the contents from being contaminated from dust, spilling, and/or evaporation much like a cork placed in the opening of a wine bottle keeps the wine clean, safe, and inside the bottle.

Mid-19th century stoppers, sometimes also referred to as plugs, were manufactured out of glass, cork, glass, and cork, or rubber. Sometimes, but not as common, a stopper was made of porcelain or ceramic. In the 19th and 20th centuries, glass was the second most common material used for bottle stoppers after cork.

The earliest known stoppers were manufactured out of straw, rags, leather, clay, or wood and date as far back as 1500 BC or 3,500 years ago! During this time in history the sundial was invented in ancient Egypt or Babylonia, glass production occurred in either Mesopotamia or ancient Egypt, ancient Egypt conquered Nubia and the Levant, the Phoenicians developed their alphabet, and the Mayan or Formative/Preclassic period developed in Mesoamerica. Glass stoppers appeared in the U.S. by 1790 but didn’t become widely used until the 1840s and 1850s for use with food containers.

Glass stoppers were primarily used with sauce bottles, decanters (an ornamental glass bottle used to hold and serve/pour liquor or wine), apothecary (medicine) bottles, perfume bottles, and inkwells. Typically, wine or beer bottles were sealed with cork or something less expensive than glass since the bottles were frequently only used once before discarding. As the invention and use of less expensive closures occurred, the use of glass stoppers declined.

Glass stoppers range in design from simple and utilitarian to decorative and ornate. No matter what the design, generally all glass stoppers are comprised of the same three parts: the shank (the piece that sits inside the container), the finial (the top part of the stopper in which you grasp to remove the stopper from the container), and the neck (located in between the shank and the finial).

Decorative finials are typically reserved for perfume bottles, decanters, and other display bottles. Glass stoppers could be either solid or hollow.

An ad for glass stoppers from the 1880s has a much higher proportion of solid versus hollow glass stoppers listed. Of the 40 types of glass stoppers listed, five are described as hollow.

Solid glass stoppers were less likely to break, unlike the hollow glass stoppers, but the hollow glass stoppers were less expensive to manufacture than solid glass stoppers. Although the glass of a hollow glass stopper expands and contracts, allowing for a high vacuum seal. Today, hollow glass stoppers are commonly found in science laboratories.

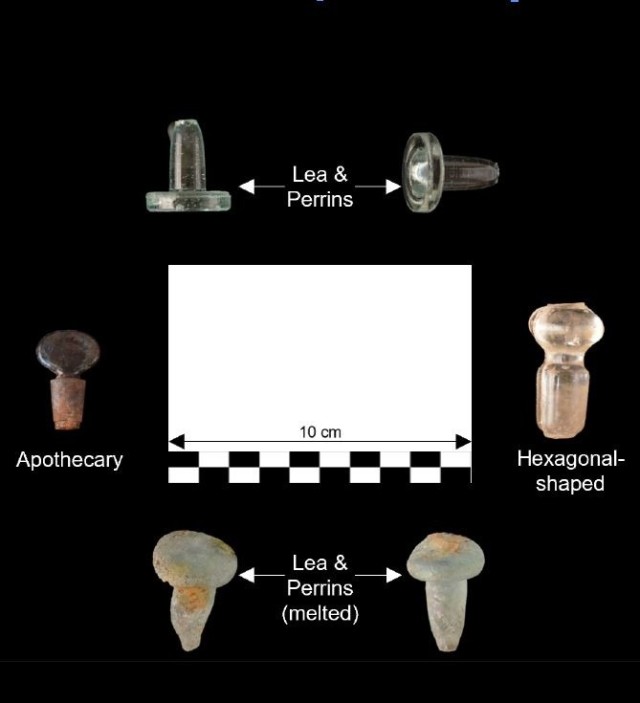

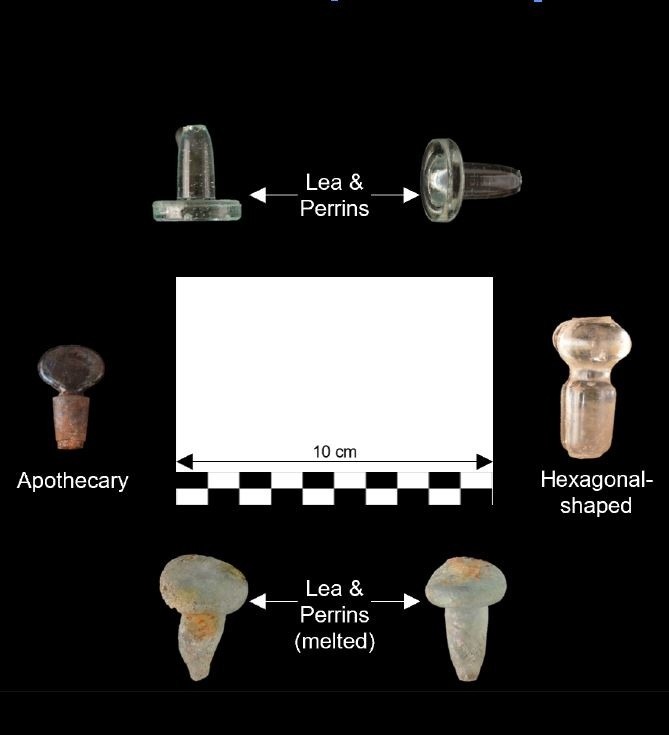

Pictured are six glass stoppers unearthed from four archaeological sites across Fort McCoy lands. The sites include a pre-World War I military training camp (one amber solid glass flat head apothecary stopper and two Lea & Perrins solid glass club sauce stoppers), two post-European contact cultural material concentrations which most likely date to the end of the 19th century and the mid-20th century (one Lea & Perrins solid glass club sauce stopper and one broken hexagonal-shaped glass stopper), and a Civil Conservation Corps (CCC) quartermaster supply base including the commissary and garages (one Lea & Perrins solid glass club sauce stopper).

Of the six glass stoppers, there is by far the most information to glean from the four Lea & Perrins glass stoppers recovered from three of the four sites, including the pre- World War I military training camp, the CCC quartermaster supply base, and one of the two post-contact cultural material concentrations.

Lea & Perrins was formed by chemists John Wheely Lea and William Henry Perrins in 1837 in Worcester, England. They specialized in Worcestershire Sauce (a fermented liquid condiment used to flavor plain foods and assisted with tenderizing tough cuts of meat) and by 1849 the condiment was exported to the United States.

The origin story of the recipe is a mystery, but all seem to agree that the original batch was forgotten in a cellar for 18 to 24 months before it was rediscovered. The chemists tried the aged concoction and found that it had fermented to a delightful, flavored sauce. They bottled the sauce and began selling it to customers.

Initially the company used plain corks to seal their sauce bottles. Lea & Perrins transitioned to glass stoppers with a cork-wrapped shank around the 1840s. This type of closure style is also known as the “shell cork and stopper” because a cork sheath (a cork with a hollow center or “shell cork”) was placed around the glass stopper shank.

This allowed for a tight seal due to the pressure of the cork-wrapped glass stopper shank pressing against the bore (opening) of the bottle. Glass stoppers that have a cork sleeve around them referred to as “Club Sauce” style glass stoppers.

The “Club Sauce” style glass stoppers pictured here are without their shell cork sleeves due to the cork deteriorating long ago. This style persisted until the late 1950s when it was replaced by a polyethylene pour plug and plastic screw-type closure.

The Lea & Perrins Worcestershire Sauce is still manufactured today and exported to over 130 countries. An assortment of Manual for Army Cooks from various years list Worcestershire Sauce as an ingredient in several recipes. For instance, the 1896 Manual for Army Cooks calls for Worcestershire Sauce as an ingredient in brown sauce, while it is found as an ingredient for oyster stew and as a condiment for fried fresh fish and fried oysters in the 1910 and 1916 manuals.

Worcestershire Sauce is still used today by the Army in recipes. An accidentally forgotten bottle in a cellar in Worcester, England has turned into a staple found in many kitchens, both big and small, and bars (calling all Bloody Mary fans) across the world.

All archaeological work conducted at Fort McCoy was sponsored by the Directorate of Public Works Environmental Division Natural Resources Branch.

Visitors and employees are reminded they should not collect artifacts on Fort McCoy or other government lands and leave the digging to the professionals.

Any individual who excavates, removes, damages, or otherwise alters or defaces any post-contact or pre-contact site, artifact, or object of antiquity on Fort McCoy is in violation of federal law.

The discovery of any archaeological artifact should be reported to the Directorate of Public Works Environmental Division Natural Resources Branch.

Learn more about Fort McCoy online at https://home.army.mil/mccoy, on Facebook by searching “ftmccoy,” and on Twitter by searching “usagmccoy.”

Also try downloading the Digital Garrison app to your smartphone and set “Fort McCoy” or another installation as your preferred base. Fort McCoy is also part of Army’s Installation Management Command where “We Are The Army’s Home.”

(Article prepared by the Fort McCoy Archaeology Team that includes the Colorado State University’s Center for Environmental Management of Military Lands and the Fort McCoy Directorate of Public Works Environmental Division Natural Resources Branch.)

Social Sharing