The Army reorganized and established the U.S. Army Electronics Command, or ECOM, at Fort Monmouth in 1962 under the newly established Army Materiel Command. ECOM would handle most of the logistics and research and development functions that formally belonged to the Office of the Chief Signal Officer. This included a work force of 14,000 people and a budget of $760 million. But it was new role for the organizations at Fort Monmouth, and there were many growing pains associated with its developing and expanding mission of supporting the supply and maintenance of increasingly complex equipment to the soldiers in Vietnam. The results of these efforts are evident in the current CECOM mission.

"Electronics has never been so vital in a war as it is here in Vietnam," stated Brig. Gen. Walter E. Lotz while serving as Assistant Chief of Staff for Communications- Electronics, US Army, Vietnam in 1966. The role and mission of the newly formed ECOM was to supply this "vital" Communications-Electronics support to the Army. This didn’t leave much room for the growing pains associated with the establishment of any new organization. The ECOM task of supplying this communications-electronics support to Southeast Asia was complicated by many factors other than just the relative newness of the Command. The type of war itself was, in fact, a complicated and important problem.

Brig. Gen. Lotz, in reference to this problem, stated:

. . . you never know where the 'front' will appear --in a small hamlet, from a hole in the side of a hill, or on a path at night where farmers had carried straw and rice a few hours before. To watch every hole and tree in the country and be able to do something about enemy action when it takes place, you need a big, organized and complicated communications system. You have to blanket the whole country with communications.

ECOM was tasked with blanketing an entire country with this vital Communications-Electronics equipment. The fast moving, mobile units operating in the extreme heat and difficult environmental conditions of SEA required the development of lightweight and mobile yet reliable families of electronics equipment.

The Army didn’t have stockpiles from which to draw, and many experienced producers of ECOM's managed items were hesitant to accept Government contracts at the expense of their booming civilian production. The electronics industry, a comparatively new industry, increased in size and volume of business very substantially in the quarter century preceding Vietnam. During the decade of the 1960's alone, the work force in the electronics industry and the dollar volume of business done each year doubled. So private industry didn’t really need the government’s business. They were “fat and sassy” as one ECOM employee called them in a lessons-learned conference. By 1967, only twenty percent of the total effort of the electronics industry was linked to the defense effort. Maj. Gen. William Latta, ECOM Commander, bemoaned this, saying “I do not think that there has even been a time in our history when so little available effort has been committed to the defense of the nation in wartime.”

In 1965, crowding in ports around Saigon meant as many as 40 ships at a time waiting to unload. Once through the port, the task became navigating the incredibly congested streets of Saigon. Then, supplies had to reach combat troops via roads that were not up to the task -- or nonexistent. Other supplies needed to be concentrated in places where port facilities were inadequate. Ships had to anchor off coast and unload their cargo onto smaller boast to be ferried in. Some troops could only be reached by air.

Unfortunately, urgent requirements from SEA often dictated that the ECOM deploy equipment which had not been fully tested for use in the intended environment. The immediacy of the situation at times meant that equipment was deployed without full support (spare parts, technical literature, and test equipment). Frequently too, fielding often occurred prior to completion of development and sufficient user training. To meet the demand and solve these and other problems, at home and abroad, the ECOM greatly expanded its effort. Civilian strengths were increased in the face of growing requirements for people to man research and development, logistics, procurement, and management functions.

Equipment

An attendee at the SEA Lessons Learned conference articulated the new role of the Signal Corps in Vietnam, “You always had the voice, but the eyes and ears, I think, was the big thing that came out of Southeast Asia.” The broad array of communications and electronics equipment used in Vietnam included radios, radars, mortar locators, sensors, surveillance systems, aerial reconnaissance equipment, air traffic control systems, night vision devices, and even cameras, which enhanced the capabilities of the Army.

ECOM, for example, developed a man-portable surveillance radar to replace older, bulkier sets. The ninety-five-pound set had a 360-degree scan capability. It could detect personnel within five kilometers and vehicles within ten. ECOM awarded the production contract in April 1966 and there were more than 350 sets in the theater by the end of 1970. Though often deadlined for lack of repair parts, the set was popular with the troops because it reduced the need for hazardous surveillance patrols. According to one commander, “One AN/PPS-5 (surveillance radar) in operating condition is worth 500 men.”

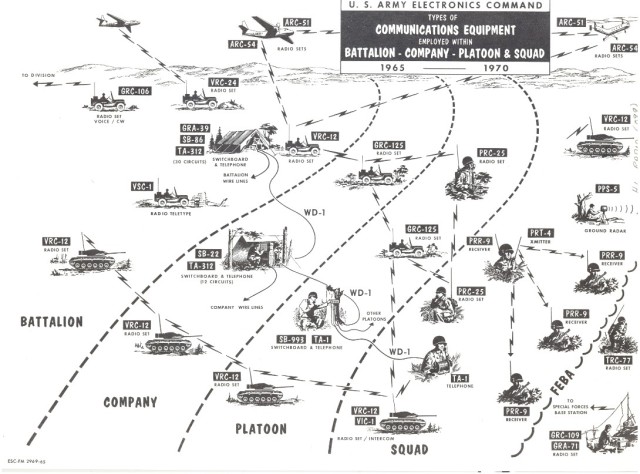

The high-technology commodities supported during the Vietnam conflict also included communications equipment. The ECOM Commander ordered the new, transistorized FM radios of the AN/VRC-12/PRC-25 families shipped to Vietnam in July 1965 in response to General William C. Westmoreland’s complaints about the existing radios. These new, transistorized FM radios of the AN/VRC-12/PRC-25 families soon became the mainstay of tactical communications in Southeast Asia. ECOM awarded competing production contracts to sustain the flow. ECOM’s commander personally browbeat contractors to ensure timely delivery of this product. The Command delivered 20,000 VRC-12 and 33,000 PRC-25 radios to Southeast Asia in three and a half years. The PRC-25 radio was, according to General Westmoreland’s successor General Creighton Abrams (1968-1972), “the single most important tactical item in Vietnam.”

The ECOM Labs also developed a helmet-mounted receiver and hand-held transmitter for squad-level use in Vietnam. This so-called Squad Radio was a significant achievement in tactical military communications because it gave the individual rifleman a communications capability for the first time.

ECOM developed and deployed night vision devices to Vietnam that made targets almost as visible at night as in daylight. "Taking the night away from [the enemy]," said Dr. Robert S. Wiseman, one time Director of the Night Vision Laboratory, "has deprived [him] of one of his greatest advantages and helped save the lives of many of our combat men.”

The radar signal detecting set AN/APR-39 provided pilots with visual and audible warnings when a hostile fire-control threat was encountered. The visual and aural displays warned the pilot of potential threat so that evasive maneuvers could be initiated. A particularly significant ECOM development during the Vietnam era was the continued refinement of the Mortar and Artillery Locating Radars, which built on products of past wars.

Maintenance

There was an understanding that the equipment would be supported at field locations whenever and wherever necessary. There was often no time to ship the equipment back to the US to get fixed, because there were no spares to take a piece of equipment’s place while it was making its way across to sea to get fixed. ECOM helped develop ways to fix equipment in theater.

A Transportable Maintenance Calibration Facility was developed to give onsite maintenance calibration and limited repair of test and measuring equipment. The facility consisted of an air transportable enclosure equipped with work benches, storage racks and drawers, and all accessories and tie downs required for the installation of the tools and test equipment. The facility was designed to be used in all types of geographical areas and climates. It provided a controlled environment for performing continuous maintenance calibration and repair under all weather and humidity conditions. In the design of the AN/TSM-55A one of the primary requirements was that the facility, fully equipped, could not exceed 4,000 pounds. This was so it could be transported by helicopter to isolated communication sites. For ground transport, the facility could be wheeled. The USARV reported the facility had "significantly enhanced their capability for instrument repair and maintenance calibration.”

ECOM also supported the floating maintenance facility aboard the navy craft USNS CORPUS CHRISTI BAY, a ship outfitted to repair the electronic equipment aboard aircraft in the war zone, primarily helicopters. The facility was on location and operational in SEA prior to 30 June 1966. Reports indicated that the Floating Army Maintenance Facility- Aircraft provided a very valuable service in support of the Army aviation mission in SEA. The concept of highly mobile maintenance facilities represented a significant change in philosophy and saved time, money, and, most importantly, lives, by ensuring equipment was out of the fight for the least possible time.

ECOM employees themselves deployed in support of the war effort, right into the war zone. Before combat troops were authorized for Vietnam in 1965, ECOM had one Department of the Army Civilian and 33 manufacturer's representatives connected with the technical assistance program in Vietnam. The civilian was expected to assist all Army elements and advisory groups working in Vietnam at that time, while the manufacturer's representatives were assisting units on commercial communications systems for which ECOM could not furnish its own Department of the Army Civilian equipment specialists due to manpower and budget constraints.

The civilian was expected to provide feedback to Fort Monmouth on usage of its equipment, maintenance and supply problems, and needs for more ECOM equipment. As more tactical and support forces began to arrive in Vietnam and troop deployments increased, ECOM realized that it needed to increase its presence in country in order to satisfy the requirements of its customers. These customers included any and all U.S. Soldiers in Vietnam, and Allied forces as requested. In addition, some cross service support was offered, for example to U.S. Marines using ECOM Night Vision devices.

According to Dan Duffy, Chief, ECOM Office, Vietnam, September 1968-March 1969, the ECOM civilians worked 10 hours days, 7 days a week and provided a broad spectrum of support. He said, “Anything they had over there, we had people working on. Satellite terminals…we worked on. Tech control facilities, switchboards- you name it.”

The civilians repaired equipment and also helped train young, inexperienced troops. The increasing complexity of the equipment used by the Army required a correspondingly longer time in which to train the operating and maintenance personnel. During World War II the average training time was about 2 weeks on anyone piece of equipment. By the end of the Vietnam conflict, the training time had increased considerably; for example, it was 19 weeks just for one secure voice communications system.

Duffy recalled, “[The ECOM civilians] went out there with the units, you know, when they had problems with the equipment and instructed the troops. We had one guy out there with night vision devices, and he would go out in the boondocks with the troops at night just to teach them how to use the crew served weapons sights and binoculars and things like that.” Despite the grueling hours, separation from his family, dangers of being in a war zone, Duffy reminisced, “I felt like I was doing something. I never worked so hard. Or enjoyed it so much.”

Lt. Gen. Thomas M. Rienzi, former commander of the 1st Signal Brigade, Assistant Chief of Staff for Communications-Electronics, and Deputy in the NATO Integrated Communications System Management Agency, remarked: "The magnitude of Army communications in the war in Vietnam … exceeded the scale of their employment in any previous war in history.”

Social Sharing