FORT DRUM, N.Y. (March 14, 2024) -- Have you been on Railey Avenue lately? Do you even know where it is located? It’s not a secret, at least not anymore.

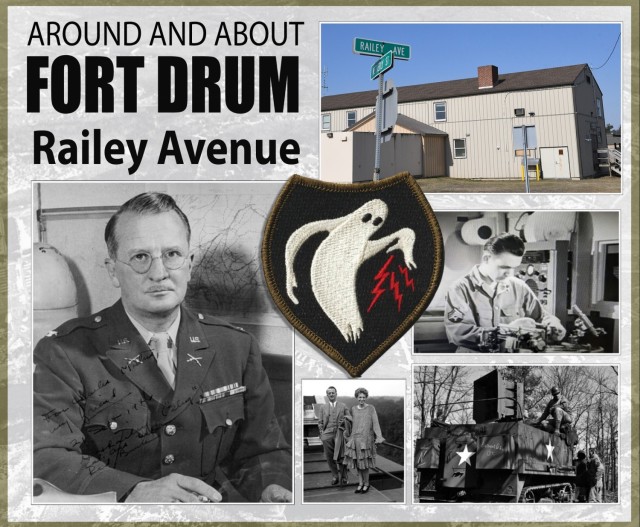

The road bears the name of an Army officer whose job here was shrouded in secrecy during World War II, with a unit that is receiving much-deserved attention this month. (Psst...it’s the Ghost Army!)

Hilton Howell Railey was born Aug. 1, 1895, to William and Lina Railey, in New Orleans, Louisiana. Railey was the great-nephew of Jefferson Davis and a descendant of several generations of New Orleanians.

Railey rejected his father’s wish to join him in the insurance business and chose to pursue acting. He was cast in minor parts in film and on stage but nothing that would amount to having a future in this profession. Instead, Railey entered Tulane University to study journalism.

He didn’t settle into his studies long before accepting a job at a New Orleans newspaper until it went out of business. He left his home state to write in Philadelphia and New York City, where he reported for the New York Evening Post.

Much of his work centered on corruption and societal vice. The War Department hired Railey to investigate venereal disease, which led to a series of articles on the conditions at Camp Pike in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Railey returned to New York City where he continued to explore deviant behavior among service members about to embark to Europe during World War I. While there, he married Julia Taylor Houston, who he first met in Arkansas, on Jan. 26, 1918. They adopted a son, Kenneth Houston Railey.

Weeks later, Railey enlisted in the Army and, coincidentally, was stationed at Camp Pike. He became an infantry officer in the Reserve and served as a war correspondent in Poland. To better understand the social conditions there, Railey enlisted in the Polish army at the request of the Polish ambassador to the U.S. He returned to America in 1921 to report on what he learned in a series of newspaper articles.

For a time, he worked for an advertising firm in Boston, and then he organized a fundraising business to finance exploration, scientific, and philanthropic advancements.

Railey helped to raise $1 million for Admiral Richard Byrd’s Antarctic Expedition in 1928, during which he made the first flight to the South Pole. That same year, Railey managed a public relations campaign for Amelia Earhart’s first transatlantic flight and made introductions to her future husband, publisher George Palmer Putnam.

In 1931, Railey attempted the first salvage operation on the Lusitania wreck from the North Atlantic Ocean after negotiating a contract with British authorities. A German submarine torpedoed the British passenger ship in 1915, killing nearly 1,200 passengers including 128 Americans. This strained relations with Germany and eventually led to the U.S. entering World War I.

Simon Lake, one of the inventors of the modern submarine, constructed and tested a vessel that could reach the wreck at a depth of 93 meters. Unfortunately, funding dried up before they could get divers underwater, and the project was abandoned when the contract expired.

It wasn’t long before Rainey returned to investigative reporting, and the subject he pursued this time was European arms industries. He allegedly encountered a Nazi agent who tried – but failed – to recruit him to spread propaganda in America.

While still in his early 30s, Railey would document his adventures as an actor, reporter, crusader, patriot, publicist, and promoter in the autobiography “Touch’d With Madness” in 1938. The title references Aristotle’s “On Tranquility of Mind,” where the philosopher wrote “There is no great genius without a touch of madness.”

By 1940, Railey was writing for the New York Times, and he co-authored a book, “What the Citizen Should Know About Civilian Defense,” published in 1942. He also wrote a confidential report for the Army about combating low morale among new recruits. Railey, still a Reserve captain, was then called into active duty with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Perhaps for the first time in his life, Railey would become involved in something he couldn’t speak or write about when he took command of the Army Experimental Station at Pine Camp (now Fort Drum).

The AES trained the 3132nd Signal Service Company on sonic deception – using sound-effect recordings broadcasted through large loudspeakers to simulate troop and vehicle movement and operations. Another unit, the 3133rd Signal Service Company, trained there but would serve in Italy outside the command of 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, which became known as the Ghost Army.

The Ghost Army also had a camouflage battalion, signal operations company and combat engineer company, whose ranks included actors, set designers, illustrators, and architects. Combined, they could mimic entire divisions of troops to deceive the enemy using inflatable tanks and vehicles, sound effects and fabricated radio traffic.

Railey, a former actor and now an Army colonel, would essentially serve as sound producer for an elaborate military subterfuge. In “Secret Soldiers,” by Paul Janeczko, Rainey is said to have personally interviewed and selected dozens of officers who knew nothing of why they were sent to Pine Camp. They scored high on mechanical and mental aptitude tests, and it was said that those assigned to the 23rd HST had the highest collective IQs in the Army. The work they would do was top secret and hidden from public view.

According to “The Ghost Army of World War II,” written by Rick Beyer and Elizabeth Sayles, the use of recorded sound to confuse the enemy was a new tactic using technology not previously available. And Railey was the perfect character to lead this program. He was described by one of his lieutenants as having the style and charisma of a great leader.

In 1944, Railey dispatched a team to Fort Knox, Kentucky, to record military maneuvers with a portable audio studio. Army audio technicians also worked with Bell Laboratories personnel on recordings. Civilian engineers used state-of-the-art techniques – such as multitrack recordings – for the Army to capture the desired sound effects.

A wire recorder, preceding the tape recorder, could capture 30 minutes of sound on a single spool that stretched two miles long. A speaker weighing 500 pounds was mounted on the back of a half-track vehicle to blast the effects that could be heard 15 miles away. Because of the intense noise and the attention it might attract in nearby communities, some tests were conducted in sound-proof chambers.

The troops deployed to Europe, unable to confide anything to family and friends about their training or mission. Members of the Ghost Army conducted successful tactical deception operations in France and Germany, often on or near the front lines. Their actions were said to have saved countless lives on the battlefield, although their accomplishments would not be unclassified for decades.

After the war, the Army Experimental Station closed shop at Pine Camp and Railey received the Legion of Merit for his leadership in 1945. The citation read:

“He demonstrated exceptional foresight and outstanding leadership in the development of a project entirely new to the United States Army. In fulfilling this mission, he exhibited a courageous pioneering spirit in the technical development and operational application of ultra-specialized signal equipment and the activation, training, and equipping of special type signal units.”

Railey divorced and remarried in 1950, with his son serving as best man at the wedding. They settled in Connecticut, where Railey began writing a biography of Nellie Green Talmadge, a local innkeeper and bootlegger. He also took up oil painting, but little more is known about his post-war life.

Railey died May 1, 1975, at age 79 in Chelsea, Maine, and is buried at the Maine Veterans Memorial Cemetery.

On Feb. 1, 2022, President Joe Biden signed the Ghost Army Congressional Gold Medal Act to recognize the service of 23rd Headquarters Special Troops. Members of the Ghost Army will be honored with the medal, which is the highest distinction that Congress can bestow, during a ceremony March 21 at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C.

Railey Avenue, located on the cantonment that is referred to as South Post, stretches past the 1st Lt. John A. McCown Light Fighters School and the Maj. Gen. Lloyd E. Jones Range Operations Center.

Today it is common to see Soldiers running or ruck marching along the road or engaged in air assault training. However, 80 years ago, this area was the classified training ground for the Army’s ingenious deceivers.

For more information about the Ghost Army, visit www.ghostarmy.org.

Social Sharing