This week marks the 80th Anniversary of Operation FLINTLOCK, the invasion of the Marshall Islands during WWII. This operation, at the time the largest amphibious assault of the war, was significant and had far-reaching effects that directly contributed to the allied defeat of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy in the Pacific. In it, both the Army and Marine Corps demonstrated the soundness of American amphibious operation doctrine, and revealed that the issues of poor planning and preparation seen in operations in the Aleutians, Guadalcanal, and Tarawa were resolved. The complex operation was swiftly and efficiently executed, and America found itself in possession of a vast swath of the Pacific, from which subsequent operations against the Japanese could be launched and won.

Although pre-invasion attacks to attrite Japanese forces in the Marshalls began as early as November 1943, the actual invasion started with D-Day on 31 January, 1944. In the pre-dawn hours, Soldiers of the 7th Infantry Division’s Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop and Company B, 111th Infantry paddled ashore in rubber boats to Cecil and Carter Islands, west of Kwajalein.

They quickly seized those islands, and then two more, Carlson and Carlos. This allowed the 7th Division to establish a fire support base on Carlson with 5 artillery battalions, to provide quick, accurate and responsive fire support to cover the landing beaches only two miles away. It also gave the attackers control over the Carlos Inlet, a deep water passage to gain access to the calmer interior waters of the atoll. There, they could more rapidly offload combat troops, supplies, and equipment, to quickly build up combat power during the assault.

The preliminary bombardment started precisely at 0700 hours on D+1, 1 February 1944. Several battleships, cruisers, and a dozen destroyers fired 7,000 rounds of high explosive and armor-piercing shells at bunkers on the invasion beaches on the west side of Kwajalein. Artillery on Carlson joined in, firing the first of 29,000 rounds they would fire that day alone. Also, carrier aviation and land-based Army Air Corps bombers dropped several tons of bombs on the defenders. One observer described the bombardment as "devastating-the entire island looked as if it had been picked up 20,000 feet and then dropped-All beach defenses were completely destroyed, including medium and heavy anti-aircraft batteries."

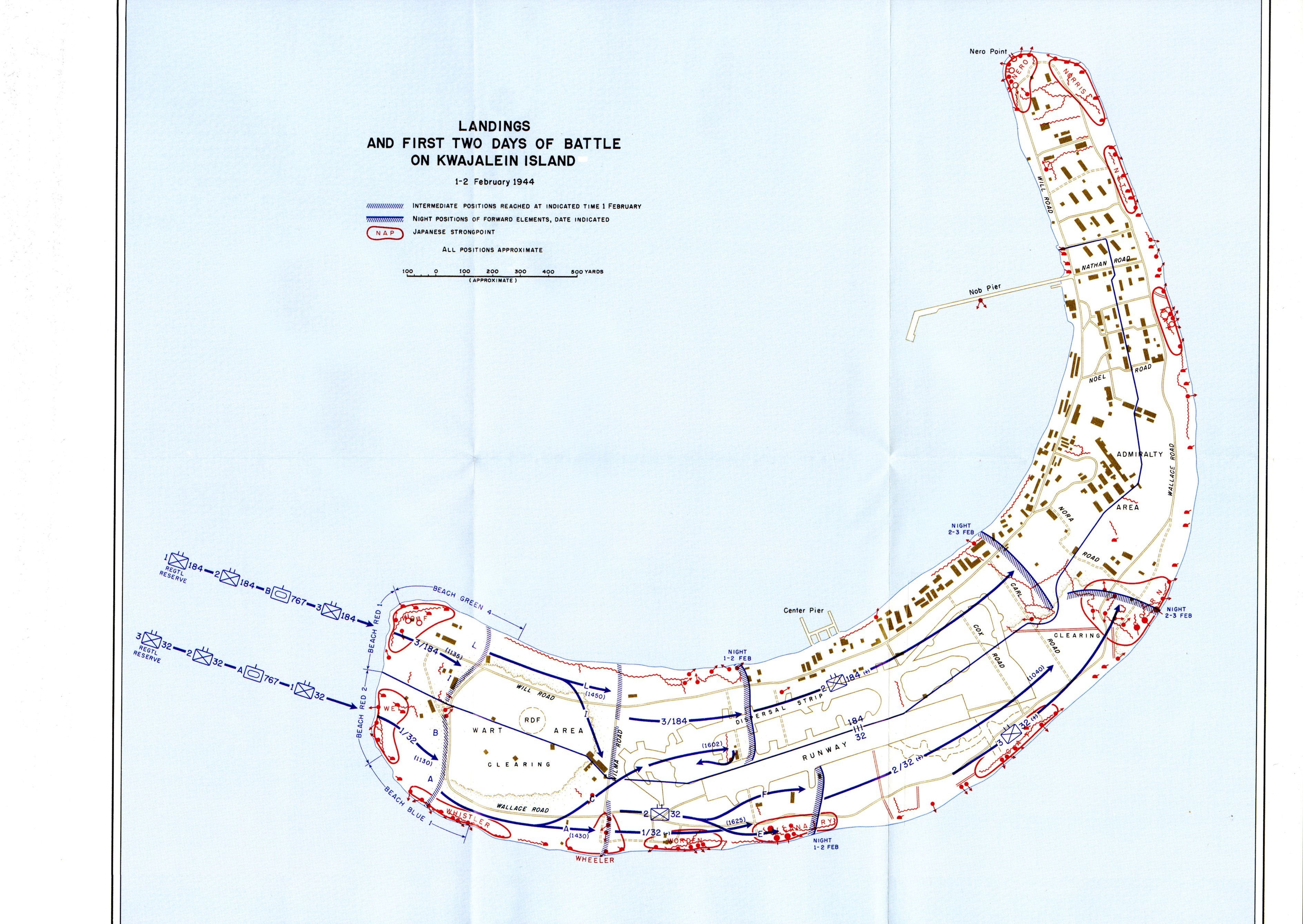

Right on schedule at 0930 hours, the preparatory fires shifted to targets inland and lead elements of two Regimental Combat Teams of the 7th Infantry Division crossed the invasion beach with two regiments abreast. The 3rd Battalion, 184th Regiment used the left two Landing Beaches, Red 1 and Green 4, and the 1st Battalion 32nd Regiment moved across Red Beach 2 and Blue 1 on the right. Since most of the known enemy strongpoints were located on the seaward (right) side of the line of advance, the 1st Battalion, 32nd Regiment’s frontage was adjusted to be a couple of hundred yards less than the left side’s zone. Despite the intensity of the pre-invasion barrage, Japanese defenders engaged lead troops with mortars and light machinegun fire. Soldiers landed in Landing Vehicle, Tracked (LVTs), landing craft, infantry (LCIs), and amphibious utility craft known as “Ducks,” and fought inland.

The impact of the pre-invasion bombardment was starkly evident. Engineers had only one pillbox to destroy on the beach; the others had already been reduced to ruins. Despite rubble from trees and fortifications, and craters from bombs and naval gunfire that impeded movement, the first four waves of the assault force were ashore by 0945.

As Soldiers moved inland, armored amphibian tractors with 37-mm. guns and flamethrowers provided support. Movement was slow and deliberate. M-4 medium tanks equipped with snorkeling gear landed in LCMs with the fifth wave, and maneuvered to support the infantry with direct fire from their 37-mm cannon. Although three tanks foundered in the surf, about eight made it ashore with that fifth wave, greatly adding to the ability of the assault elements to reduce enemy fortifications. Slowly, but steadily the troops fought east across the island, by noon reaching the edge of the runway and the dispersal strip alongside it. Behind the assault echelons fresh units moved across the beach and moved into staging areas in case they were needed. Logistical units established ammunition and supply dumps, despite the lack of depth to the lodgment.

Typical of the action that day was that of PVT Parvee Rasberry and PFC Paul Roper, Company K, 184th Regiment. After moving inland about 25 yards from the landing beach, they encountered fire from a hidden pillbox. Taking shelter in a crater, they threw grenades at the enemy without much effect. A flamethrower was employed, but the flames proved ineffective on the concrete. But when PVT Rasberry was able to get a white phosphorus grenade into the position, it forced the enemy to evacuate, subjecting them to rifle fire. Some survivors reoccupied the pillbox, and the whole process repeated until the enemy were completely eliminated. They then called up a tank or amphibious tractor to completely destroy the structure so it couldn’t be used again. The two then moved on to the next position and began anew.

These soldiers, like all the others of the 7th Infantry Division, used tactics and techniques for reducing the enemy bunkers that were first learned, practiced, and mastered during their pre-deployment training in Hawaii, before embarking for the Marshall Islands. There, at special Jungle Training Schools, and on specially built range complexes, the Soldiers practiced the techniques of reducing obstacles and positions until they were perfect. That advanced individual and small unit training saved countless lives during the invasion, allowing the Soldiers to quickly and efficiently reduce and eliminate enemy strongpoints and bunkers.

The drive continued over the next three days. But as the island narrowed and turned to the left, it complicated fire support coordination and establishing clear fires as the right units began drifting in from of those on the left. Finally, the Division halted movement for the night of 3 February and issued a new order for the 32nd Regiment to finish off the last 600 yards or so of island clearing remaining. After fending off five night attacks by desperate Japanese, the fresh attack kicked off on the morning of the 4th of February, and by that afternoon the island was declared secure.

Overall, the island had been secured at a minimal cost. U.S. forces suffered 177 killed and 1,000 wounded on Kwajalein, but only 125 Korean laborers and 49 Japanese survived out of 5,000 defenders. Americans estimated that between 50 to 75 percent of the Japanese were killed in the preparatory bombardments. Earlier intelligence reports of substantial defenses proved to be exaggerated. Most of the fortifications clearly had been hastily constructed, but were deadly just the same.

As fighting ended on Kwajalein, the 7th Division quickly consolidated its prize. Support and engineer troops immediately rebuilt the island as an American base. Only days after the cessation of fighting Kwajalein's airfield was functioning, and American planes started attacking the remaining islands still under Japanese control. In the meantime, the 4th Marine Division finished up its own invasion of the twin islands of Roi-Namur in the northern Kwajalein atoll, and both divisions tightened their hold on the Central Pacific.

The conquest of the Marshall Islands demonstrated the soundness of American amphibious doctrine, albeit on a smaller scale than practiced later in the war. As with earlier operations, American planners acquired much experience in the campaign and applied new techniques which would be shaped and refined for subsequent operations. Two of the most important lessons involved close air support and naval gunfire. Before 1944 continuous support from those services was more the exception than the rule. With the destruction of Japanese naval and air forces as the war progressed, and given American industry's tremendous output in ships and planes, the possibility of greatly increasing air and naval pre-invasion fire support became both feasible and desirable.

The relatively easy seizure of the Marshalls and the effective neutralizing raids on the Japanese fortress of Truk proved the soundness of Nimitz's decision to use the Central Pacific as the best route to Japan. By neutralizing and bypassing Truk, Nimitz saved many lives with no loss of tactical advantage. The Marshalls provided the same facilities as Truk for both fleet anchorages and airfields for future operations. In addition, the 3+ divisions designated for a possible landing on Truk were able instead to prepare for the seizure of the Marianas, where strategic plans called for islands to become long-range bomber bases for the aerial strike on the Japanese home islands.

The quick seizure of the Marshall Islands allowed Admiral Nimitz to advance the date for the invasion of the Marianas by almost six months. At the same time, Japanese preparation time for the defense of islands like Saipan and Tinian was shortened, and many of the U.S. units that had participated in the Marshalls operation, still relatively intact, were made available. The overall importance of the rapid seizure of the Eastern Mandates thus cannot be overestimated. The Marshalls were not only a proving ground for new tactics and innovations but also a critical step in a chain of events that led to the Japanese surrender at Tokyo Bay. Another example of the innovation and adaptability of U.S. Army Forces in the Pacific, and the impact of their contributions to the American war effort.

Social Sharing