Editor’s note: The name of the victim is not used to protect her identity.

PORTLAND, Ore. – It was the sound – something like a scream – that first caught their attention.

On the red deck of the massive dredge vessel Yaquina, deck mechanics Tanner Ensworth and Brian Marshall had just returned from a quick run with a small launch boat and were securing the launch boat to the side of the mother vessel.

The Yaquina, slowly chugging up the Columbia River, gorged itself on sediment it sucked up from the river bottom, clearing the channel of large sand mounds called shoals and thereby keeping the federal navigation channel clear for other vessels.

Ensworth and Marshall paused in their work and exchanged a look.

“Did you hear that?” Marshall asked.

The deck of the Yaquina is a song of sounds: its engines roaring, the choppy waves walloping the hull, the wind sprinting past.

But this sound was not part of the usual cacophony – and the vessel’s crew were always listening for equipment that sounded “off” – which could be a sign of a malfunction.

The two scanned the water and shores as the Yaquina inched along the river, a few miles south of Reed Island near Washougal, Wash. The nearby beachless shores offered no place for people. They were effectively in the “middle of nowhere,” and the water around the dredge vessel was empty of boats.

Seeing nothing, Ensworth and Marshall returned to their work.

Then, it punctured the chorus of noise on the deck: a clear scream of, “Help!”

…

An hour before, a woman strolled out on a sandbar three-and-a-half miles upriver, as many do on Oregon mornings. The day, which started out in the 50’s, promised to be hot and hazy – the 90-degree heat had returned.

The woman walked with her feet in the cold water that flowed from snowmelt in British Columbia, more than 1000 river-miles away.

In one step, the sand quickly shifted beneath her, and she fell into the water. The woman tried to right herself, to stand – but the sand gave way under her, and the Columbia River swept her into its white-capped, hypothermia-inducing embrace.

…

To work aboard the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ dredge vessels requires discipline. Nearly every crewmember has multiple jobs while aboard. This is all in service to the Yaquina’s mission: to dredge federal navigation channels at ports and harbors, and in busy rivers that host barges of wheat and other goods outbound to and inbound from overseas destinations.

This discipline means that everyone responds when the alarm rings and the announcement from the bridge booms: “Man overboard.”

Crews learn that time is a critical factor for someone in the water: Symptoms of hypothermia set in when the body dips below 95 degrees Fahrenheit. According to the Coast Guard, in water that is 60-70 degrees, exhaustion or unconsciousness can begin within two hours. In that same temperature range, the expected time of survival is between two and 70 hours, depending on the person.

On that day, Aug. 24, 2023, river gages at Bonneville Dam – just 20 miles upriver from Reed Island – measured the Columbia’s flows at a temperature of 69 degrees.

…

For a moment, Marshall caught sight of something – someone? – in the water.

That day, the wind rippled the water, layering waves across the horizon and making a visual scan of the water difficult.

Unable to determine whether it was a Coast Guard buoy or something else, Marshall stepped back onto the secured launch boat, where a pair of binoculars were kept near the wheel.

Marshall scrutinized the river again and then caught sight of a person.

Marshall pointed to her, and both he and Ensworth could see she was barely making it: She was bobbing in the water, in and out of view, repeatedly going under.

Ensworth took the binoculars while Marshall bounded up the Yaquina’s shallow steps to the bridge and announced to the dredge operators, “Someone’s in the water.”

The crew on the bridge notified Captain Erich Krueck, who ordered the bridge to sound “man overboard.”

On dredges across the Corps, the crews regularly perform drills to respond to a man overboard situation. When the alarm sounds, it scrambles the rescue boat team. The dredge comes to a halt. The medical crew prepares supplies. The chief mate steps into the role as the on-scene lead and reports to the captain. The steward and cook oversee muster – making sure everyone is onboard and accounted for.

Ensworth joined the rescue boat coxswain, Craig Wilson, on the deck at the davit that would lower the smaller, quicker vessel – a rigid hull inflatable pontoon. The design is stable, light, and fast, making it the most effective way to reach someone in the water. There, Wilson and Ensworth climbed into the boat, and crews lowered it from its cradle into the river.

Krueck ordered the Yaquina to maneuver in a position to best pick up the rescue boat when it returned.

“With winds like we had that day, you have to position the ship just right,” he said.

Those same winds were complicating efforts for Wilson and Ensworth in the rescue boat. Once in the water, the wind-whipped waves obscured the view of the woman. Ensworth, who had jumped up on the bow of the boat for a better vantage point, kept losing sight of her.

“I see her. Then she’s gone. Then she comes up again. And then she disappears.”

Wilson radioed back to the Yaquina:

“We can’t see her.”

But the drills had prepared the crew for this: Along the decks of the Yaquina, five members of the crew were posted and pointing in the direction of the woman. As Wilson piloted the rescue boat, Ensworth continued to glance back at the lookouts to call directions out to Wilson: “To the right!”

Ensworth finally spotted her arms, and Wilson steered the boat toward her.

“We got you,” Ensworth called out to her. “We’re right here, and we’re going to pull you in.”

Hypothermia will quickly eliminate executive function – the cognitive skills used to coordinate and control other cognitive abilities and behavior. The coxswain and deckhand observed that she was not responding to direction. The woman, desperate for rescue, grabbed for “anything and everything” and Ensworth struggled to pull her aboard as Wilson kept the boat steady.

“We finally pulled her up, and I kept talking to her, saying, ‘I’m Tanner, I’m here and I’m going to be with you the whole way,’” said Ensworth.

In the rescue boat, as Wilson directed them back toward the dredge vessel, Ensworth held the woman’s head in his lap. Ensworth remembered that she kept a “death grip” on his leg as the boat hurtled over the waves.

“She seemed to be slipping in and out of consciousness and wasn’t all there,” said Wilson. “She kept calling for help, even after she was onboard.”

The woman had shed everything that was sinking her in the current – her jacket and shoes were lost to the river, and she was left with her shirt, leggings, and socks. Her lips were blue, she was stuttering and she couldn’t say her name.

Meanwhile, the captain reached out to the Coast Guard for rescue assistance. But the Yaquina was too far from Coast Guard assets – it would be an hour before they would reach the Yaquina. The chief mate contacted the vessel’s remote medical provider, who advised the captain how to stabilize her once she was in the Yaquina’s care.

Wilson motored the rescue boat along the Yaquina, and the crew used the davits to hoist the boat back onboard the dredge vessel. The crew wrapped the woman, who was unable to stand, in the ship’s brown and black wool blankets and swept her into a small onboard hospital.

For the next hour, multiple members of the crew hovered over her, assessing her vital signs, providing medical care and working to raise her core temperature enough to stabilize her.

Once stabilized, the crew would put her in a launch boat and bring her to shore. The Coast Guard and sheriff had coordinated resources, and at Steamboat Landing – a dock in Washougal, Washington – an ambulance would be waiting for the woman.

“I’ve done drills for 15 years, and I’ve never had anything like this happen,” said Krueck. “We were lucky to be in the right place at the right time.”

For an hour, the crew worked to bring the woman’s temperature up, then loaded her onto the Yaquina’s small launch boat, where Wilson and Ensworth were ready to take her to shore and deliver her to paramedics.

“This was a reality check that life changes fast and you have to be ready,” Ensworth said. “You have to train like everything’s real.”

Then, the Yaquina and the crew quietly returned to work, dredging the vast and fast Columbia River.

In the Yaquina’s log – a green, canvas-covered, federal supply-issued record book – the captain entered the events of the rescue, which reflected the success of all their training: From the time the deckhands first heard a cry of, “Help!” to having the woman onboard, only nine minutes elapsed.

-- 30 --

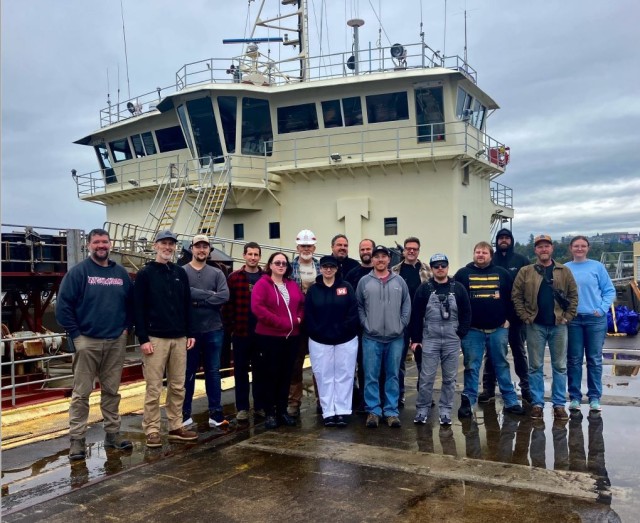

Editor’s note: As stated in the story, everyone on the Yaquina’s crew has a job to perform when the “man overboard” alarm sounds. The crew of the Yaquina, and their role in the rescue, are listed below.

Erich Krueck – Captain

Eric Risheim – Assistant Captain

Austin Wittman – Bridge Team, conning officer during rescue

Chris Ochs – Bridge Team, lookout, communications and assistant conning officer during rescue

Michael Lange – Engine control booth

Michael Morrisey – On scene Leader, led medical assessment and worked with remote medical-care provider

Craig Wilson – Fast rescue boat coxswain, pulled victim out of water, launch coxswain when taken ashore

Tanner Ensworth – Fast rescue boat deck hand, pulled victim out of water, on launch crew that took the victim ashore

Brain Marshall – POC and davit operator for launching rescue boat and launch

Logan Conlan – Lookout, spotting victim and tracking them until rescue boat pick up

Tom Martincello – Lookout, spotting victim and tracking them until rescue boat pick up

Matt Carlsen – Lookout, spotting victim and tracking them until rescue boat pick up

Jake Moreland – Lookout, spotting victim and tracking them until rescue boat pick up

Keith Ashby – Lookout, spotting victim and tracking them until rescue boat pick up, assisted by carrying victim to and from hospital

Brian Campbell – Lookout, spotting victim and tracking them until rescue boat pick up, assisted by carrying victim to and from hospital

Aslyn Fisher – Provided medical assistance for victim once onboard

Faith St John – Provided medical assistance for victim once onboard

Samantha Orem – Provided medical assistance for victim once onboard

Social Sharing