For Larry Carlile, successfully managing military training lands, while conserving that same land as habitat for endangered species, is a process grounded in solid communications, professional skill, and a keen understanding of mission.

As the chief of the Fish and Wildlife Branch at Fort Stewart/Hunter Army Airfield, the work of Carlile’s team today flows directly from the successful work and leadership of the past to build a sustainable future for the installation.

“The mentors I had when I first started working here were just fantastic. Linton Swindell was great, he always trusted that we knew what we were doing, and he let us do it. When Tim Beaty became the branch chief his door was always open. He would always be willing to talk about things and was willing to change course based on input from his staff. He wanted to make sure we got things right,” Carlile said.

“I’ve continued that tradition as branch chief. If my people have an idea or think we’re doing something wrong and could do it better, I want to hear about that,” he said. “We have a great team here.”

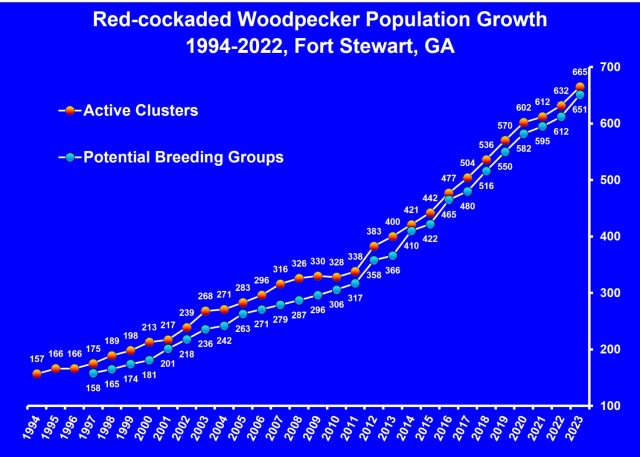

At Fort Stewart/HAAF, the most notable success is the conservation and recovery of the installation’s red-cockaded woodpecker population, which achieved the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s recovery goal of 350 pairs in 2012.

“I’m particularly proud that decades of proactive management of longleaf pine ecosystems have not only helped the species thrive, but also resulted in the elimination of military training restrictions associated with the RCW,” he said. “We keep in mind that our mission is to support military training, and we also create regular communications and dialogue to show the installation leadership that we are here to support them and to make their lives easier.”

“When we all know we are interested in achieving the same goals, it’s remarkable how much we can get done,” he said.

One key to the success of the red-cockaded woodpecker program is conservation of longleaf pine forest habitats, which need regular fire to thrive and provide suitable habitat for the woodpeckers and other listed species.

“All of the species that we are most concerned about on Fort Stewart benefit from controlled burns to create the right habitat conditions,” he said. “The gopher tortoise and the eastern indigo snake are good examples of how this works. The snakes use the burrows dug by the tortoises, so when you improve conditions for the tortoise, you improve conditions for the snake. Our system relies on having open, mature, well-burned habitat.”

Carlile, who began his career at Fort Stewart/HAAF in 1994, spent time in the deserts of Arizona and the pine forests of Georgia while growing up in a military family. He loved being outdoors and was particularly interested in birds.

“When we lived in Phoenix, there was open desert just across the street from our house,” he said. “My mother didn’t particularly like it, but I would walk to school by going straight through the desert. I loved being outdoors, I just didn’t realize that you could make a career out of it.”

From that love of nature, years of experience successfully managing habitats while supporting the training mission, has helped lead to Carlile’s involvement in the multi-agency conservation policy initiative that he believes will have significant positive impact.

“The national initiative, which was launched by Department of Defense natural resources team and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, recognizes that much of the conservation work going on in this country is being done by the DOD and at military installations and lands,” he said.

Carlile said by undertaking broader coordination, helping establish best practices, and by creating more efficient process, the initiative has the potential to create more success stories about preserving the vital training land needed to meet military missions, while seeking to balance that with smart, effective land stewardship practices that in turn protect and preserve the species found on DOD lands.

The initiative, which launched in 2020, now has two pilot programs; the Georgia Pilot Project that covers Forts Stewart, Moore, and Gordon and the Joint Base Lewis-McChord Pilot Project near Tacoma, Washington. In addition to the federal partners, the Natural Resources Institute at Texas A&M University facilitate the efforts to move from pilot program to national model.

“We think this can go a long way toward relieving unnecessary administrative burdens and will allow both greater accountability to species recovery goals with a recognition of the core mission of providing training lands,” he said. “It all points to recognition in our regulations and several different guidance documents that makes clear that we can’t continue training if we destroy the habitat. Regulatory processes can be burdensome and can get in the way of that.”

Social Sharing