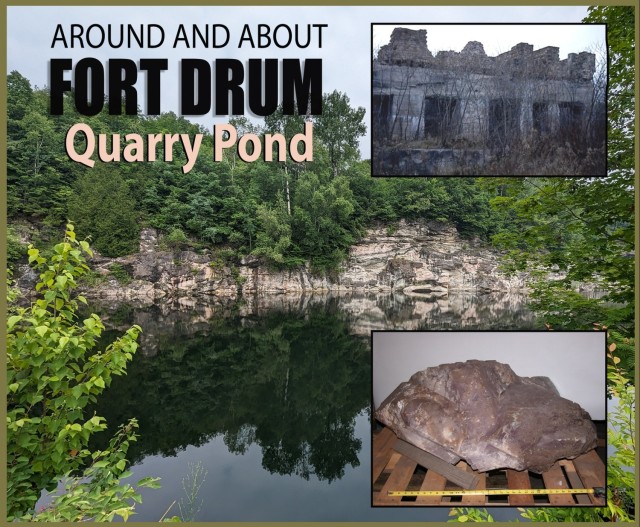

FORT DRUM, N.Y. (Aug. 18, 2023) -- The deep, cold spring water of Fort Drum’s Quarry Pond, located in Training Area 14B, is a popular trout fishing spot for local anglers. But at the turn of the 18th century, its relevance was less recreational and more industrial in the North Country as a site for limestone mining.

Mining and mineral processing was a major industry in New York, and the Lewisburg quarry (originally known as the Louisburg Quarry) played its part in supporting the community by providing limestone for the village’s iron blast furnace.

According to a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers report, evidence indicated the lime was burned on site to make iron. Lime also was used on farms as fertilizer, and in plaster and mortar for construction.

After the furnace closed in 1848, the quarry continued to supply the limestone used by sulfite mills in paper production and the steel industry.

In 1902, the quarry was renamed the New York Lime Quarry, when it was acquired by new owners, along with a processing mill at Natural Bridge. The new owners increased limestone production and had equipment for crushing stone installed at the quarry.

Drilling operations were steam-powered to bore holes into the rock for explosives. Upon detonation, the rock broke down into smaller pieces and workers loaded them onto flatcars by means of a steam-powered shovel to be sent three miles away to the processing plant in Natural Bridge.

By this time, the mine had been excavated to a depth of 60 feet, which left a high perpendicular wall overshadowing the mining operations below. Quarry work was dangerous, and miners were susceptible to injuries from falling rocks.

On one fall day in 1906, workers ran for cover after hearing the grinding sound of sliding rock. Looking up, they saw an opening in the face of the cliff. One daring miner scaled the wall and was stunned by what he saw.

As described in the “History of Lewis County, N.Y. (1880-1965),” the miner was momentarily blinded by “brilliant flashes of rose and amethyst” as reflected rays of sunlight bounced back from the giant calcite crystals within the cavern.

The other miners were called up to see the amazing discovery. Moving past the narrow opening, they entered a grotto roughly 10 feet wide and five feet high and extending about 20 feet into the face of the cliff. Scattered throughout the floor were “beautifully formed calcite crystals in shades of pale lavender and pinks.” One crystal weighed over half a ton.

“There’s a certain magic to the Crystal Cave,” said Dr. Laurie Rush, Fort Drum Cultural Resources manager. “Can you imagine what it must have been like that day? These workers going about their business and then suddenly, the whole backside of the quarry comes sliding off and reveals all these amazing rose quartz crystals in this cave.”

One of the property owners was concerned that mining operations might damage the crystals and sought their preservations. A geologist from the New York State Museum in Albany was charged with packing the crystals for shipment, and it took museum staff six weeks to accomplish. It was estimated that 14 tons of crystals were removed and packed in 80 barrels, 14 kegs, and 22 boxes.

A proposal was made to reconstruct a grotto to display the crystal collection in the museum. By all accounts, it was painstaking work to accurately replicate the original cave and delicately place the crystals within – and only two crystals were damaged in the process.

Dr. John M. Clarke, state geologist, supervised the project, which opened to the public on June 13, 1909. It proved to be a popular exhibit, and long lasting too. After nearly 70 years, the display was dismantled in 1979 when the museum was moved to new buildings.

“Children could go to the museum and walk through this crystal cave and see all these beautiful crystals that were lit up,” Rush said. “Those crystals became iconic in the state of New York because of that exhibit.”

Back at the “Crystal Cave” in Lewisburg, mining work resumed for another two decades or so, and this might have been the end of the story if not for another accident by nature.

Sometime in 1931, the mining crew blasted a new vein in the rock that hit a natural spring and began filling the quarry with water.

“The pumps had failed, and almost with no warning at all the quarry was flooded,” Rush said. “All the workers fled, mining operations stopped, and everything they left is still down there.”

Ten years later, the property was acquired by the U.S. Army for the Pine Camp expansion.

In 2008, the Lewis County Sheriff’s Department dive team visited Quarry Pond for a training event to refine their skills. Divers located the system of railroad tracks and a railroad car used for transporting minerals from the quarry. They also located a flywheel for a steam shovel and a 1953 Chevy car.

Early in her career at Fort Drum, Rush approved an environmental project at Quarry Pond that unearthed an assortment of artifacts, including several gauges of train tracks and a railcar air brake made from the Watertown factory.

Realizing how much was unknown about Quarry Pond, the Cultural Resources Branch initiated a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers study that was published in 2012.

“Based on their findings, we now have a better understanding of what we call the Quarry Pond Archaeological Complex, which includes the railroad berm and lime kilns,” Rush said.

Along with being a recreational fishing spot, Quarry Pond has been included in history tours, staff rides and educational programs at Fort Drum.

“And the thing is, we are still learning and making new discoveries there. For example, Meg (Schulz) found where the cable car system began, and where the anchors are. There is still lots to learn, and it’s always interesting to visit Quarry Pond.”

(Editor’s Note: Article based on research from the Fort Drum Cultural Resources Program, the “History of Lewis County, N.Y.,” edited by G. Byron Bowen, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ 2012 report)

Social Sharing