Barely seen among the trees and shrubbery, enemy soldiers in tiger-striped camouflage uniforms and face paint lay in wait along both sides of the gravel road. With weapons ready, they are prepared to strike any unsuspecting friendly troops that might come by. Automatic weapon fire persisted in the background, punctuated by explosions.

Further ahead, an enemy combatant lay face-up, left arm outstretched with his condition unclear. Was he wounded or dead?

This was not an active combat zone; it was Cadet Field Training at Camp Buckner. The "enemy soldiers" were members of the 82nd Airborne Division from Fort Liberty, North Carolina, acting as opposing forces to the rising second-class cadets of the U.S. Military Academy to help them develop skills in small-unit tactics and leadership.

But tactical training wasn't all the cadets were being exposed to. Maj. Benjamin Ordiway, instructor of Officership for the Simon Center for the Professional Military Ethic (SCPME), and Lt. Col. Kevin Cutright, academy professor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Philosophy, were at Camp Buckner to capture another dimension to the training — the “moral terrain.” Ordiway believes that Soldiers’ training should go deeper than learning to respond to threats within the physical and human terrain. He argues that navigating the moral terrain with purpose is as fundamental to the military profession as tactical decision-making.

For the past four years, Ordiway has developed and researched “Moral Terrain Coaching” (MTC), a semi-structured interview that encourages Soldiers to consider factors, such as their physiology and emotions, and the capacity for reason that distinguish them as human beings. He recently presented his work at the U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) headquarters. The audience was familiar — Ordiway is a Special Operations Civil Affairs officer. In this capacity, he grappled with moral questions during his second deployment and began to recognize the need for better training.

"I started to have a suspicion that I was not very well trained for the moral dimensions of what I was being asked to do,” Ordiway said.

In 2019, the Simon Center selected Ordiway to serve as an SCPME Fellow. He would teach one year in the Department of English and Philosophy as a PY201 (Philosophy and Ethical Reasoning) instructor, followed by two years as an MX400 (Officership) instructor. This led him to look at different models the Army used to teach moral reasoning. He soon realized that they did not seem to fit with experiences in the field or while on deployment. This disparity prompted him to consider a more experiential approach to developing moral competency.

Ordiway first explored this approach in his graduate writing sample to the University of Michigan. The article, “Fixing the Problem: Integrating Virtue Ethics into U.S. SOF Selection, Education and Training,” published in the “Civil Affairs Association Journal,” was a response to the 2020 “USSOCOM Comprehensive Review of Special Operations Forces (SOF) Culture and Ethics.” While in graduate school, Ordiway followed up with another article published in “Special Warfare Magazine” in March 2022: “Developing SOF Moral Reasoning: Preparing Humans for Hard Wear on the Moral Terrain.” Between the two articles, Ordiway describes typical ethics instruction conducted within operational military units. Instruction often takes place in a classroom and is informed by theoretical models that overlook the interplay of reason with, among other things, intuition and emotion. MTC aims to move ethics education beyond the classroom and into field training so that servicemembers may experience and reflect upon realistic moral challenges.

"There are enough moral features inherent in existing training — there's no need to make an ‘ethics lane.’ It just takes someone educated and trained to focus on observing the moral dimensions,” Ordiway said. "Where there is emotional engagement with a specific moment in training on the part of the servicemember, there's often a sufficient inroad to discuss the moral component of the training."

Ordiway demonstrated an example of this approach in the field. After a squad completed an ambush, Ordiway approached a cadet and conducted a quick brief, first asking if the cadet was comfortable discussing the experience of encountering the wounded enemy soldier.

Once the cadet agreed to an interview, Ordiway led the cadet to a spot several yards from the lanes to a half-tent, where he designed the setting to create a psychologically welcoming environment. Two chairs sat facing each other along the back tent flap, and a log for additional seating ran parallel to the chairs on the open side of the tent. To help set a relaxed tone, Ordiway provided a cooler filled with sports drinks and snacks.

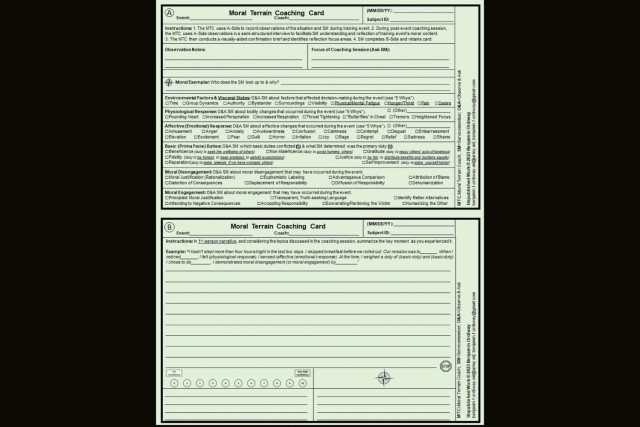

Using the Moral Terrain Coaching Card with pre-formatted questions, Ordiway opened with, "Tell me about someone you look up to and why?" This preliminary question addresses a topic the participant will feel at ease discussing. It also serves to unearth concepts we might call virtues.

Ordiway then asked a series of questions divided into five categories — environmental factors and visceral states, physiological, emotional, basic duties and moral disengagement — that can impact decision-making. One visceral state is fatigue, often associated with a lack of sleep. This cadet only slept four hours the previous night, broken up by guard shifts, but remained focused on the mission despite this.

Being hungry is another visceral state. This cadet had skipped breakfast but planned to eat later.

An environmental factor is the presence of an authority figure, and Ordiway asked if there was anyone the cadet had on his mind during the exercise. He answered that he was focused on the time pressure to get through his task, being conscious of his squad leader's proximity.

Next, Ordiway asked the cadet to describe the position of the enemy soldier and whether he had a weapon, followed by the cadet's emotional response to approaching him. The cadet replied he felt anxious, frustrated, angry and confused.

At this point, Ordiway switched back to the present, asking the cadet, “How does your body feel now compared to then?” The cadet said he felt much calmer than earlier when his heart was beating faster and he was sweating, both physiological responses to the stress of the exercise.

Ordiway then moved to the next category: basic duties. Ordiway asked the cadet to consider if and how the specific physiological responses and emotions might relate to one or more duties. In this case, the cadet identified an initial duty to ensure the well-being of his squad by eliminating a threat, but he also identified a duty not to inflict unnecessary harm. Ordiway then prompted the cadet to consider what he saw as his primary duty and suggested that the cadet’s actions might serve to answer that question.

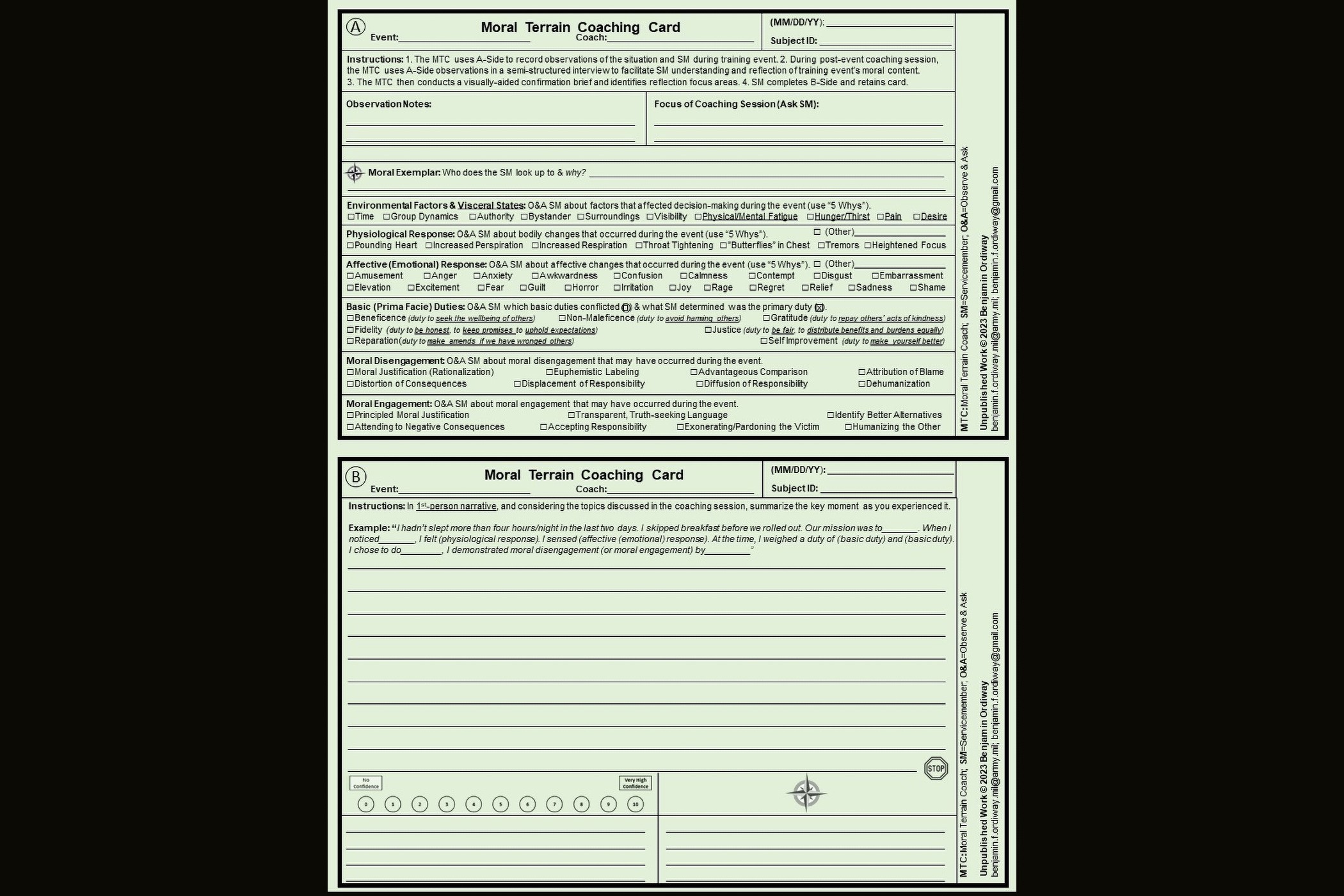

Once they covered all the Moral Terrain Coaching Card categories, Ordiway had two final questions to prompt reflection: “How would your moral exemplar have responded to this situation?” and “What have you learned from this experience that you can share with others?” On the coaching card's reverse side, the cadet synthesized the separate components covered in the coaching session in a first-person narrative to encourage personal reflection.

After releasing the cadet back to his platoon, Ordiway pointed out that the most important discussion is not the coaching session; it's the one cadets have with their peers, perhaps while pulling perimeter guard during field training or while in their Philosophy or Officership classes. Ultimately, Ordiway intends to make MTC blur the line between education and training so servicemembers get the most out of classroom discussion and training exercises while the stakes are relatively low.

Outside of USSOCOM and USMA, foreign allies are taking notice of MTC. Upon returning from Athens, Greece, where he presented at the International Society for Military Ethics Conference, Ordiway received an invitation from Royal Military Academy Sandhurst to share his work with faculty training observer-controllers.

To learn more about the Simon Center for the Professional Military Ethic, visit William E. Simon Center for the Professional Military Ethic | United States Military Academy West Point

To learn more about the Department of English and Philosophy, visit English and Philosophy | United States Military Academy West Point

Resources mentioned in this article:

“Fixing the Problem: Integrating Virtue Ethics into U,S, SOF Selection, Education, and Training” (https://media-cdn.dvidshub.net/pubs/pdf_63722.pdf)

“Developing SOF Moral Reasoning: Preparing Humans for Hard Wear on the Moral Terrain” (https://www.dvidshub.net/publication/issues/63722)

Social Sharing