As the weather warms up, many Wisconsinites will begin shifting their activities from indoors to outdoors. There will be many gatherings with friends and family sitting around the campfire enjoying each other’s company and making new memories. Although campfires can be built all year long, nowadays they are most often a spring and summer social event.

But in ancient times, a campfire was far more than just a means for entertainment, it was a necessary tool for survival. Ancient campfires were not only for socializing they also provided protection from animals, and were the only source of heated cooking, light, and warmth.

Based on existing evidence, Australopithecus robustus and/or Homo erectus, the ancestors of modern humans (Homo sapiens), made campfires roughly 1.6 million years ago in South Africa.

Mankind’s ability to create and harness fire is a beneficial technology that has survived the test of time. Archaeologists learn valuable information from studying “campfires,” such as when the campfire was used through radiocarbon dating charcoal remains and what the fire was used for through studying the bits and pieces that remain of the hearth.

Archaeologists use the term “hearth” rather than campfire and define it as the remnants of a purposeful fire. Prior to European contact, Native Americans built hearths for the same reasons we build campfires today, such as cooking, warmth, light, and socializing. Hearths were also used for thousands of years during pre-contact times to heat-treat stones used for fashioning tools to make them stronger and less likely to crack or break during tool manufacturing.

More recently, but still before European contact, hearths were used for firing pottery, which would result in a more durable material that would retain its shape even if wet.

Hearths come in all shapes and sizes. How do archaeologists identify a hearth if there is so much variety? They look for evidence like inorganic material used to outline the hearth and hold the heat (rocks, bricks, etc.), burned organic material (wood, plant remains, animal remains, etc.), and evidence of combustion such as indicators of heat (fire-cracked rock or FCR and burnt earth) and fuel (wood).

The oldest known human-made campfire found at Fort McCoy dates to approximately 10,000 years ago and was found at an archaeological site on South Post.

This nearly two-foot by one-and-a-half-foot oval-shaped hearth was identified as a soil discoloration with several pieces of FCR within and around the discoloration.

Although hardly any artifacts were recovered from the feature itself, there were plentiful amounts of charcoal to collect from it. The charcoal samples were sent in for radiocarbon dating at a specialized laboratory and returned a calibrated radiocarbon age ranging from 10,185 to 9,605 years ago (+/- 40 years). These dates fall primarily within the Late Paleoindian period (10,000 to 8,000 years ago, or 8000-6000 BC).

Pictured with this article are examples of two different types of hearths that were excavated by archaeologists with Colorado State University’s Center for Environmental Management of Military Lands (CEMML) during the 2014 field season.

The first hearth looks similar to something one might construct today by placing rocks in a ring around the intended location of the fire. This hearth is a circular arrangement consisting of 18 sandstone slabs of varying sizes.

Not all of the hearth was unearthed as it extended beyond the limits of the excavation unit, but the outer circle of the rocks indicated the hearth was roughly two feet in diameter. Unfortunately, there was no charcoal present, so the hearth could not be radiocarbon dated. No diagnostic lithic artifacts nor pre-contact ceramics were recovered from the site making it impossible to assign a date to a specific era.

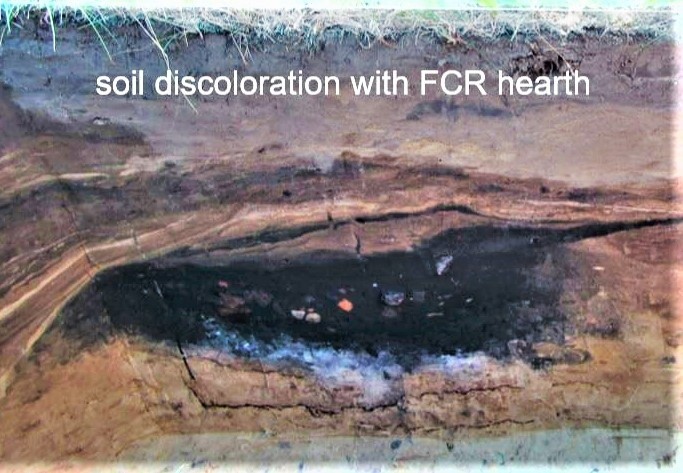

The second hearth pictured is an ancient style more commonly found by archaeologists and appears as a bowl-shaped soil discoloration in the side of an excavation unit.

This hearth was also circular and contained both fire-cracked rock (FCR) and burned sandstone. The rocks were not distinctly arranged in a circle like the first hearth, suggesting it may have been more of a “fire-pit” style hearth. Like the first hearth, this one extended beyond the limits of the excavation unit. The visible portion of the hearth suggests it was nearly three feet wide and a foot or more in depth.

This hearth contained abundant charcoal which provided a radiocarbon age range of 3,055 to 2,870 years ago (+/- 30) after calibration, which dates the hearth to the Late Archaic period (3,500 to 2,500 years ago, or 1,500-500 BC).

A lot can be learned from a hearth including when it was used and why it was used. If present, archaeologists can examine the charred plant and animal remains to determine what was being cooked at the fire.

The presence of heat-treated chert, a type of raw material used to fashion stone tools, can also indicate that the hearth was being used to heat-treat the chert to make the rock stronger and more resistant to cracking and breaking while manufacturing tools such as an arrowhead.

So, remember, when you are sitting around the campfire with your family and friends and scraps of your food that you are cooking fall into the fire, a future archaeologist may come across it in fifty, a hundred, or even a thousand years from now and ask, “What was for dinner?”

All archaeological work conducted at Fort McCoy was sponsored by the Directorate of Public Works Environmental Division Natural Resources Branch.

Visitors and employees are reminded they should not collect artifacts on Fort McCoy or other government lands and leave the digging to the professionals.

Any individual who excavates, removes, damages, or otherwise alters or defaces any post-contact or pre-contact site, artifact, or object of antiquity on Fort McCoy is in violation of federal law.

The discovery of any archaeological artifact should be reported to the Directorate of Public Works Environmental Division Natural Resources Branch.

(Article prepared by the Fort McCoy Archaeology Team.)

Social Sharing