JOINT BASE SAN ANTONIO-FORT SAM HOUSTON, Texas (May 23, 2023) -- Instead of the indispensable childhood experiences of play, relationship building and sense of security foundational in the development of a child, a contracting intern and her family instead found themselves captive in a years-long attempt to escape the brutal Khmer Rouge regime and the aftermath of civil war in Cambodia.

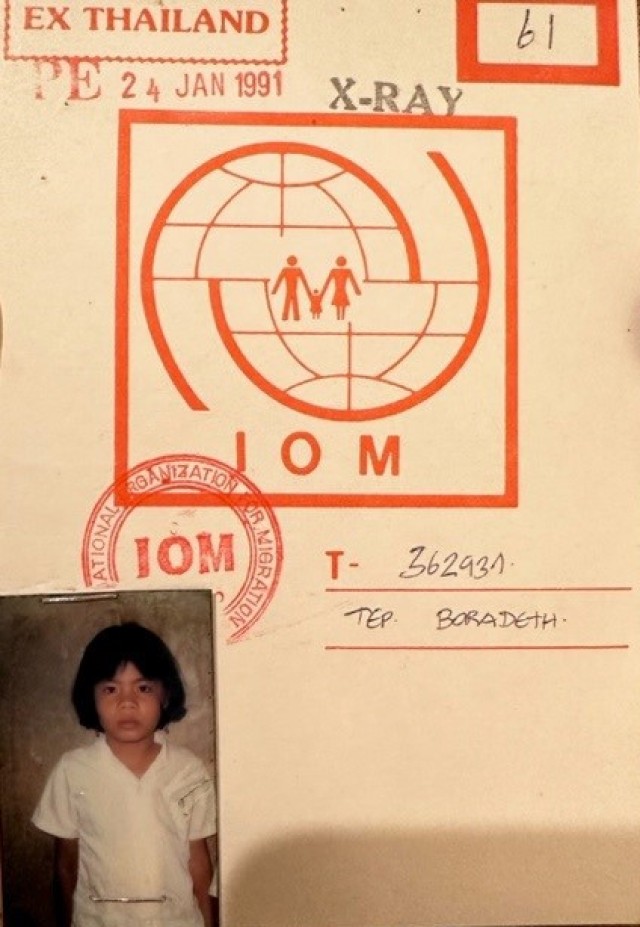

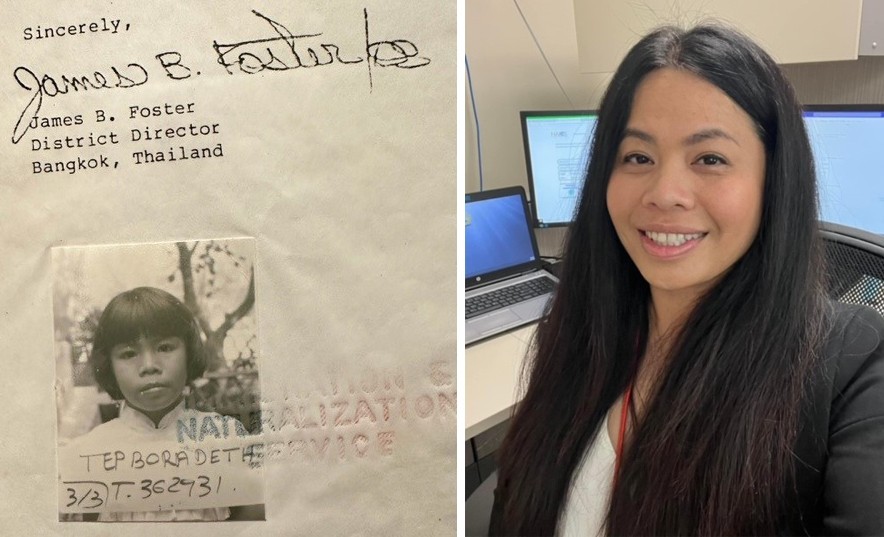

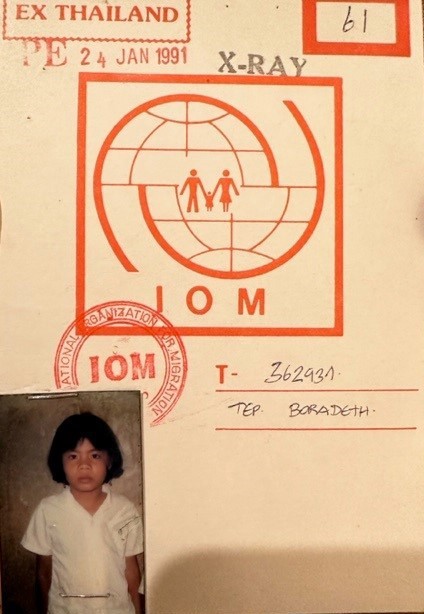

From age of 2 to 7, Bora Delassus, a contract specialist with the Mission and Installation Contracting Command office at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, and her parents languished in camps along the Cambodia and Thai border region surrounded by wires desperately awaiting safe passage to the United States. A decade earlier, Communist-supported insurgents forced the fall of Cambodia resulting in the evacuation of U.S. diplomatic and military personnel from Cambodia ahead of brutal tactics put in place by the Khmer Rouge.

Each May, the Army observes and reflects on the tremendous contributions of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders to the nation and its history as part of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. For Delassus, who joined the MICC as an intern in October 2021, those contributions encompass writing and administering contracts for many of the essential daily services in support of Soldiers and their families at Fort Meade and Fort Detrick in Maryland.

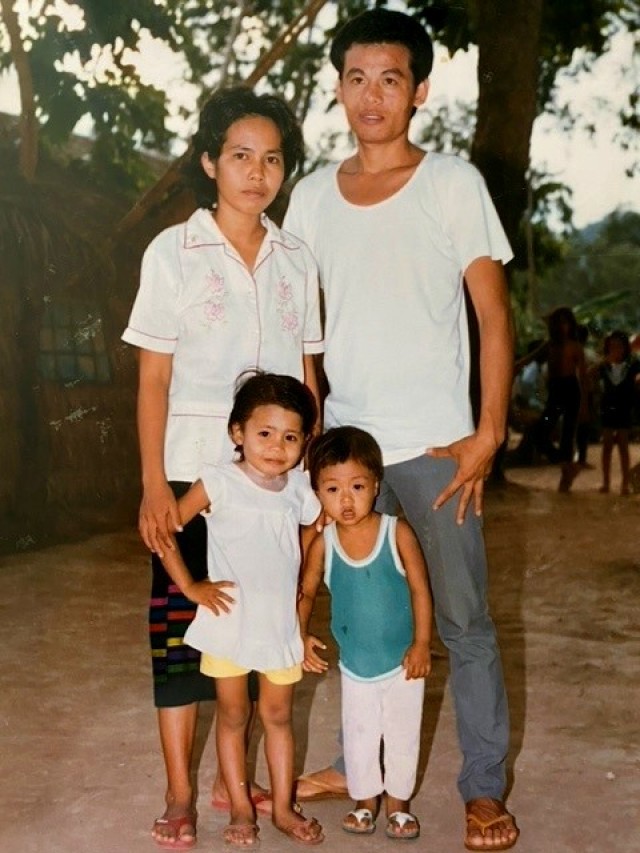

Born in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, following the civil war between the Communist Party of Kampuchea and Kingdom of Cambodia, Delassus recalls that limitations to education resulting from the rule of the Khmer Rouge led her parents to make ends meet by selling items along with other street vendors in the war-torn country.

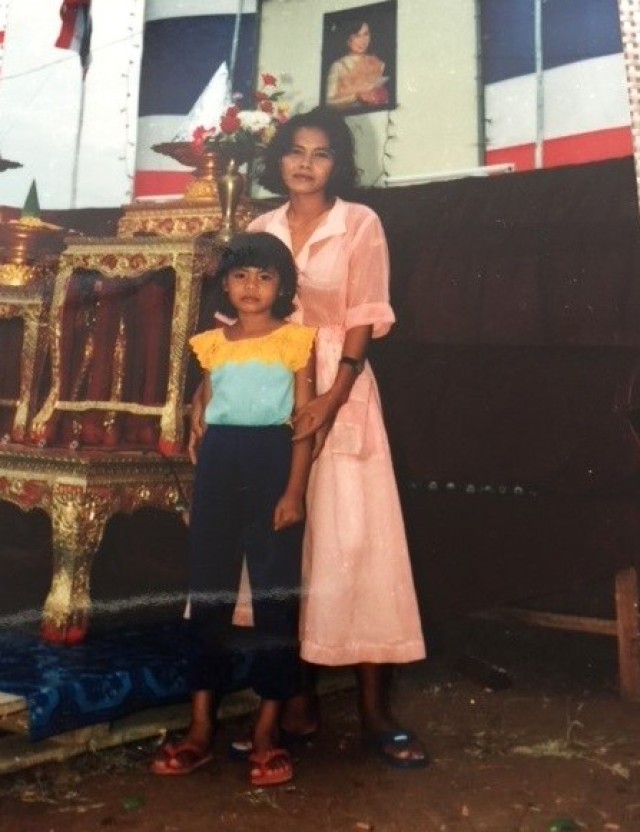

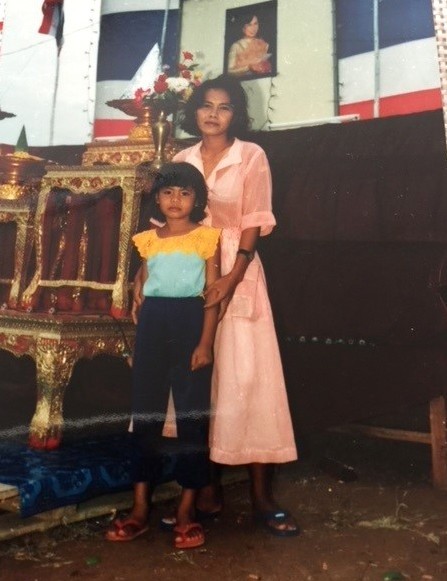

“Since they only had an elementary school education, they couldn’t do much after the war,” she said. “My mom and I crossed over the Thailand border together with a few other people. We decided to leave Cambodia because there was no future in that country for our family. We had an opportunity to flee, and we did. We escaped through the rice fields and turned ourselves into the Thai police.”

Yet, despite the refuge they so urgently sought, they instead found themselves imprisoned.

“We stayed in prison until they transferred us to the first camp, where all the refugees where living,” she said.

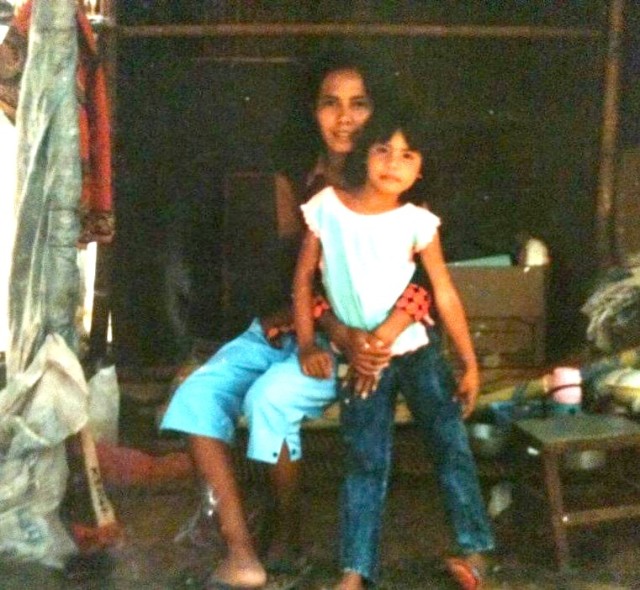

Established to offer immediate, short-term assistance while providing protections from violence for those crossing the border, the sheer number of those fleeing Cambodia led many to spend years in refugee camps. Delassus explained that while there was little to do from day to day while in the refugee camp, learning proved to afford some semblance of normalcy for the thousands then being held there.

“The only thing that was provided was a half-day school for all the kids, a bag of rice, 20 liters of water once a day, and sometimes canned tuna,” Delassus said. “The United Nations provided a Chinese class for reading and writing. I utilized that because they provided bread and candies. After school, we would play until dinner.”

Nonetheless, her days in the refugee camp were often punctuated with violent reminders of chaos that also became routine.

“Around the Thai and Cambodia border, there were many shootings. Bombs would go off, and we would run to the ditch and cover,” she said. “When this occurs every single day for years, you get used to it.”

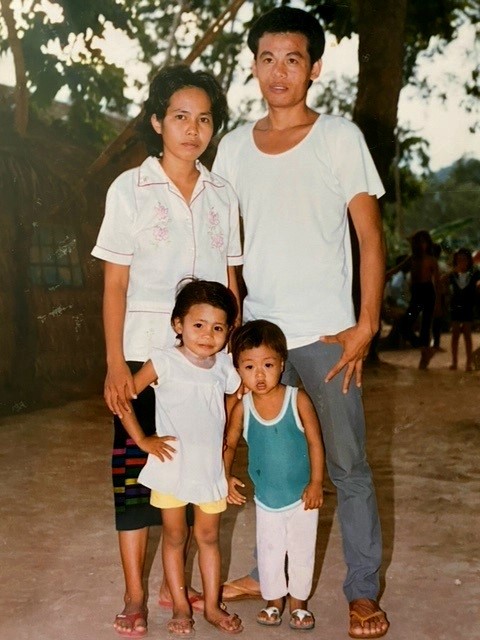

Delassus said some being held at the camp made the grim decision to return to war-torn Cambodia unable to survive off of the paltry amount of rice provided. She and her parents managed to survive the struggles of remaining at the camp thanks to money her uncle, Sam Chau, would send to help them while they awaited sponsorship.

“When Vietnam invaded Cambodia, the troops guarding my parents were called away to fight. This allowed my parents the chance to survive,” she said. “Many others in the camps with my parents were not as lucky. Both of my parents lost family members to the Khmer Rouge regime.”

During the civil war, her uncle served in the Cambodian Navy. With the fall of the Cambodian government, he was informed that he could no longer return to his country and given the option to move to the United States, eventually settling in Lancaster, South Carolina. It was from there his efforts to help rescue his brother’s family, including a young Delassus, began in earnest.

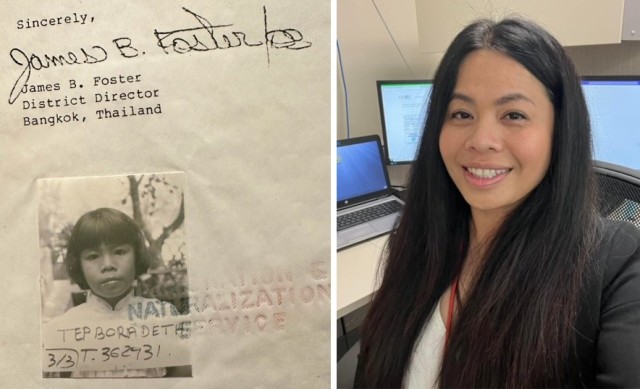

Her uncle worked with U.S. officials to sponsor Delassus and her parents as well as his brother and family. His ceaseless efforts came to fruition with the successful emigration of Delassus and her parents to Lancaster March 11, 1991, when she was 7 years old.

Facing inadequate employment opportunities in South Carolina, the family decided to move to Atlanta. Unable to drive, her parents quickly found it quite challenging to live in such a large city and instead followed a lead from a growing Cambodian community of hopeful employment in factory work at the smaller city of Columbus, Georgia. There they were able to save and fulfil the American dream of buying a home.

“Growing up was hard since we didn’t have much until I was in middle school. It was difficult in school. Kids can be mean; however, they didn’t know any better,” she said. “Besides the language barrier, I had a difficult time eating new food that I had never seen before in my life. After a few years, I got accustomed to it. As far as education goes, learning English was very difficult. I had to learn it at home by myself by watching cartoons, but I also had an amazing English as a second language teacher that helped me throughout grade school.”

Overcoming such dire circumstances early in life, Delassus went on to graduate from Shaw High School in Columbus in 2003. She went to work in residential management a few years later after her parents chose to relocate to Las Vegas following her high school graduation. Deciding to remain in Columbus, it was while she was working as a leasing consultant for an apartment complex that she met and established a friendship with Maj. Dave Delassus, who was a tenant at the time. She later moved to Dallas for almost a year before also relocating to Las Vegas. Although separated, their enduring friendship led the two to marry in October 2010 following his return from deployment to Iraq.

At the encouragement of her husband, she continued her education by going on to earn a Bachelor of Business Administration from Campbell University in Lillington, North Carolina, and Master of Business Administration from the University of Maryland Global Campus.

Demonstrating that the Army opens the door of opportunity to Americans from diverse backgrounds to build a career pathway, she joined the MICC as an intern contract specialist at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, following her husband’s experience with the 928th Contracting Support Battalion at Grafenwöhr, Germany, and subsequent move to the Pentagon. There he serves as a branch chief and planner for the operational contract support division at the Chairman of the Joint Staff Directorate of Logistics. He is responsible for plan reviews, current operations, vendor threat mitigation, and operationalizing and institutionalizing operational contract support throughout the joint logistics enterprise. His work with the Joint Staff has included DOD support to the COVID-19 response, Operation Warp Speed, Afghanistan retrograde, Afghanistan non-combatant evacuation operation, Operation Allies Welcome, Southwest border mission, Taiwan security assistance, and Ukraine security assistance.

“After seeing my parents struggle, I knew I wanted to work in a career field that would reward me with opportunities that my parents never had. I wanted to work in business or a business-related field,” she said. “After my husband left the Infantry and became an Army contracting professional, I became intrigued by his work. It seemed interesting to me hearing about contracting. And since we move around a lot, I decided maybe I should give it a try. MICC-Fort Belvoir allowed me that chance when a position came available.”

Army officials estimate that the service is comprised of approximately 4 percent Asian and 1 percent Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders, contributing experiences essential in a diverse workforce. Bora Delassus, 39, leverages her childhood experiences of the repressive Khmer Rouge and cultural challenges of adapting to a new country by dedicating her energies to the contract needs of Army Soldiers and their families.

“I try every day to deliver the best capabilities for our Soldiers through contracting. I want to help make the Army the best that it can be so that it can be the best Army in the world,” she said. “The Army is a force for good and can help prevent another Khmer Rouge in the world.”

About the MICC:

Headquartered at JBSA-Fort Sam Houston, Texas, the Mission and Installation Contracting Command consists of about 1,300 military and civilian members who are responsible for contracting goods and services in support of Soldiers as well as readying trained contracting units for the operating force and contingency environment when called upon. MICC contracts are vital in feeding more than 200,000 Soldiers every day, providing many daily base operations support services at installations, facilitate training in the preparation of more than 100,000 conventional force members annually, training more than 500,000 students each year, and maintaining more than 14.4 million acres of land and 170,000 structures.

Social Sharing