by Lt. Col. Richard L. Farnell, U.S. Army and Lt. Col. Michael A. Hamilton, U.S. Army

All around the Army there are Soldiers with different backgrounds, interests, and goals who converge on units like the ones YOU will soon join. People from all walks of life come together in the Army to serve a common purpose - all of them yours to lead. All of them.

How do Army officers successfully lead such organizations? For anyone serious about doing it well, this fundamental question deserves serious contemplation. The Army defines leadership as “the activity of influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to accomplish the mission and improve the organization” (ADP 6-22). Thus, influencing and motivating people of all types is at the very core of Army leadership. While technical skills, tactical expertise, and other professional competencies are very important to Army leaders, the competencies that fundamentally matters the most in influencing people are interpersonal skills. Such so-called “soft skills” are frequently underappreciated and overlooked in leader development efforts; however, it is critical to not only deliberately cultivate these skills, but to do so in a manner that engages and affirms people of all types and backgrounds in diverse organizations. By being self-aware, approachable, and receptive to feedback, leaders can assess and develop their interpersonal skills for empathy, humility, tact, building trust, and communication required to lead diverse organizations.

#1. Be Self-Aware – Leaders who are self-aware intentionally reflect on their own beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and the leadership outcomes they manifest. If leaders are not naturally inclined to this kind of self-reflection, it absolutely must be a conscious, deliberate effort that critically evaluates their own interpersonal strengths and weaknesses. Self-aware leaders are mature enough to recognize that they are not perfect, and actively seek to understand their own shortcomings, biases, prejudices, and preconceptions. Self-aware leaders are cognizant of how others view them, and consciously calibrate their interactions with others to compensate for negative perceptions and friction. They are also sensitive to social and cultural dynamics that may influence interactions within their team, and they adjust their communication style to accommodate these dynamics in order to have the desired effect.

#2. Be Approachable – Leaders who are approachable have more opportunities for communication and engagement, which directly contributes to the leader’s ability to influence subordinates, address their concerns, improve their quality of life, and elicit motivation and buy-in. Approachability can be a complex aspect of leadership to achieve for Army officers, and it requires a great deal of self-awareness as described above. Approachable leaders make their subordinates feel comfortable in honest and open dialogue, which enables the candid feedback essential to effective leadership. In order to accomplish this, leaders must routinely:

a) understand how they are viewed by their subordinates.

b) understand the challenging social dynamics of gender, race, religion, culture, and economic status—along with their associated presuppositions and biases—and how they potentially undermine camaraderie, trust, and teamwork.

c) be sensitive to power dynamics, and how they frequently inhibit openness in hierarchical organizations.

d) create an environment that tolerates honest mistakes and imperfect performance for the sake of learning, growth, and development.

e) judiciously let down their guard around their subordinates and tolerate a degree of temporary informality and relaxed military courtesies appropriate to the situation and the desired engagement.

f) focus primarily on identifying problems and solutions, not assigning personal fault or blame.

g) focus on and emphasize commonality, not differences.

The importance of leader approachability to aligning a wide & diverse range of cultural values, beliefs, and attitudes with Army Values and the unit’s mission cannot be overstated. Each Soldier comes into the Army with their own personal values that leaders must acknowledge if they are to be successful in inculcating and integrating the Army Values with individual values and beliefs. Candid, open, and frequent communication between Soldiers and approachable leaders is best path to achieving this alignment of values that is so crucial to influence, motivation, and leadership.

#3. Be Receptive to Feedback – The final component to improving one’s interpersonal skills is openness to feedback. The combination of self-awareness, approachability, and receptiveness to feedback complete the assessment chain necessary for personal growth. Similar to scientific experimentation, self-awareness is the hypothesis—an educated guess of one’s interpersonal strengths and weaknesses; approachability sets conditions for feedback through engagement to confirm or disconfirm one’s personal views; therefore, receptiveness to feedback is imperative in order to sincerely accept the conclusions and recommendations of individual and group assessments. The biggest hurdle to being receptive to feedback is having the humility to accept the perceptions and judgments of others, whatever they may be. There’s no way around it: If you want to improve your interpersonal skills, you must be prepared to accept negative criticism with an open mind. Doing so in earnest requires leaders to challenge themselves by soliciting this feedback from all perspectives – diversity matters here. Leaders must solicit feedback from peers and subordinates of different demographics—race, gender, rank, etc—to leverage these different perspectives.

Putting It All Together: Assessing and Developing Interpersonal Skills

Being self-aware, approachable, and receptive to feedback puts leaders “in the driver’s seat” in control of their own self-development by equipping them the information needed to assess the character attributes and leader competencies required to lead. But where are they headed? FM 6-22 Developing Leaders provides an invaluable guide to developing the interpersonal skills necessary to successfully lead diverse organizations. There is a common misconception about interpersonal skills being viewed as static, immutable, and inaccessible to growth and development. Fortunately, this is false – leaders absolutely can and should develop their interpersonal skills as an essential leadership competency. Utilizing the Army Leadership Requirements Model (ALRM) consisting of “Be, Know, Do” leader attributes and competencies, FM 6-22 provides a clear path to deliberate self-development of interpersonal skills that is crucial to successful leadership. Among the numerous character attributes and leader competencies described in the ALRM, the ones most relevant to interpersonal skills needed to lead diverse organizations are empathy, humility, interpersonal tact, building trust, and communication. Chapter 4 of FM 6-22 is particularly helpful in providing a detailed guide of developmental activities for cultivating these attributes and competencies in a comprehensive way. As an example:

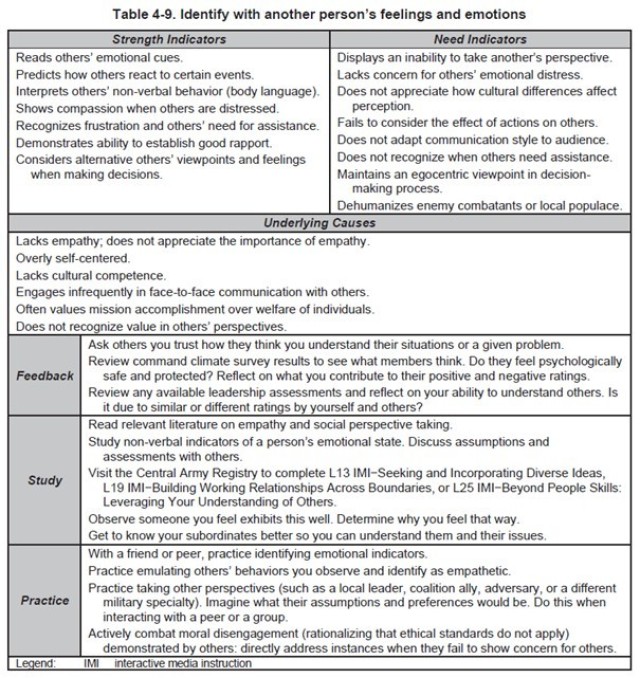

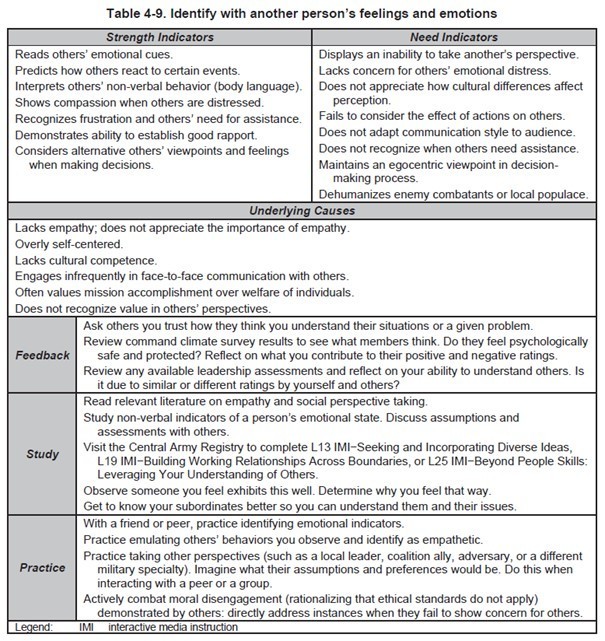

Character attributes: Empathy – Table 4-9 of FM 6-22 describes leaders with strong empathy react to others’ emotional cues, demonstrate the ability to establish good rapport, and considers alternative viewpoints and feelings of others when making decisions (FM 6-22, Table 4-9). In contrast, leaders who lack empathy display an inability to take another’s perspective, do not appreciate how others cultural differences affect perception, and do not adapt their communication style to their audience (FM 6-22, Table 4-9). Underlying causes of a lack of empathy include self-centeredness, a lack of cultural competence, and an underappreciation for others’ perspectives (FM 6-22, Table 4-9). Leaders seeking to improve their empathy should participate in the feedback, study, and practice activities as prescribed in Table 4-9 (see table for reference).

Conclusion – Professional officers who are committed to providing exceptional leadership are serious about self-development. Too often, this self-development is only focused on obtaining professional knowledge, education, and training on technical and tactical competencies, without regard to the interpersonal competencies required to effectively lead Soldiers of a diverse, all-volunteer force. This kind of leadership is indeed the most powerful – that which motivates soldiers beyond their mere obligations to follow orders, but understands them as they are, and bonds them together in a cohesive team that values their contributions and perspectives. All Soldiers deserve this kind of leadership, and it takes deliberate effort to learn and apply, starting with the simple recognition of its importance.

Social Sharing