KOSOVO - According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 21 percent of people in the United States of America speak another language, other than English, at home. While 78 percent of Americans speak only one language, this can make things difficult for them abroad. The stories of those who can speak additional languages, and how they learned it, can often be as interesting as the language itself.

U.S. Army 1st Lt. Aivaras Bartkaitis is a Medical Operations Officer with the 2nd Battalion, 151st Infantry Regiment, 76th Infantry Brigade Combat Team (IBCT), Indiana Army National Guard and was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The son of Lithuanian immigrants, his parents had a hard time raising him and his siblings due to their financial situation. Bartkaitis, his brother and sister were sent to Lithuania to live with their grandparents and godparents. When he turned 16, Bartkaitis and his siblings returned to the United States and finished high school before enrolling in college and the Army National Guard.

Bartkaitis says he speaks fluent Lithuanian and English, but also grew up knowing Russian as well.

“In Lithuania, the Russian language is very common as well,” Bartkaitis said. “I want to say I’m fluent in Russian; I would say I understand it and can speak it to a fourth-grade level, because I’m struggling to keep up that language skill.”

Russian was a required language for all the Soviet States and was a secondary language of Lithuania, when it was part of the Soviet Union after World War II.

“They [Lithuania] had a very historical event called the Russification,” Bartkaitis said.

Russification began under the Tsars, or Russian emperors, in the late eighteenth century and continued until the collapse of the Soviet Union, December 26, 1991. The Russification was a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, gave up their culture and language in favor of Russian culture and language.

“The language is a very sacred part of Lithuanian culture because we had to deal with the whole situation of Russia trying to get rid of our language and having to do underground schools, books, smuggling and all that to keep the language alive,” said Bartkaitis.

Bartkaitis said though the Soviet Union collapsed at the end of 1991, many of his relatives still spoke Russian and it was used in many tv shows and books. He added that it became a second language that was offered in schools, but was not mandatory.

“I just picked it up from being around relatives and talking to other people,” Bartkaitis said.

Bartkaitis noted the similarities between his picking up of Russian and the Soldiers he is currently serving with in Kosovo, learning up Albanian.

“It was kind of the same situation especially when you went into a restaurant. They would have Lithuanian written and Russian written right underneath, or the street signs would have Lithuanian written on top and Russian beneath it, so it was a very quick way to pick up things,” Bartkaitis said.

Cultural immersion is another way to learn a language. When a person is engaged in a culture, they have the opportunities to pick up the language and understand it. Bartkaitis said a lot of the culture comes from slang or humor, and is a direct reflection of the area.

“When you know the language, you understand more of the culture; where the language came from and the culture puts you in a better perspective [to learn] how people live in a different part of the world,” said Bartkaitis.

U.S. Army Sgt. Logan Babcock agreed that cultural immersion is a great way to learn another language.

A Soldier with the Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 76th IBCT, Indiana Army National Guard, deployed to Kosovo, Babcock studied at Indiana University and enrolled in the Turkish Flagship program. This program was different from most because the students would meet with a native speaker twice a week, conduct one-on-one conversations and the speaker would also help them study. He also said the students would do language immersion trips within Indiana and speak in Turkish throughout the weekend with the native speakers.

“I also did a summer and two semesters abroad at Baku Language University, in Baku, Azerbaijan,” Babcock said.

Traveling to Azerbaijan, Babcock continued his program there. He still stayed with families who were from Turkey, but lived and worked in Azerbaijan.

“It was a unique challenge of not only trying to learn Turkish abroad, but also trying to learn Turkish in a country where Turkish isn’t necessarily the dominant language,” Babcock said.

Babcock was drawn to learning Turkish and had always associated it with the Ottoman Empire being the bridge between the East and West in Asia and Europe. He also said the Turkish language uses the Latin alphabet, which was an attractive feature of the language.

Babcock has used his Turkish language in Kosovo during a trip to the city, Prizren. Turkish is also one of the minor languages of Kosovo and Babcock had several conversations in Turkish with some of the locals.

“I think they expected that we would all speak English to them, so it was cool I could talk to them in Turkish,” Babcock said.

Kosovo Force hosts a contingency of Turkish Soldiers and Babcock used that as an opportunity to practice his additional skill.

“I’ve been able to interact with the groups of Turks who work with us, as part of our Kosovo mission,” Babcock said.

He said the Turkish Soldiers are often taken aback at his ability to speak Turkish with them.

“It’s a less studied language throughout the globe, so it’s very surprising when they [Turkish Soldiers] find somebody able to speak it,” Babcock said.

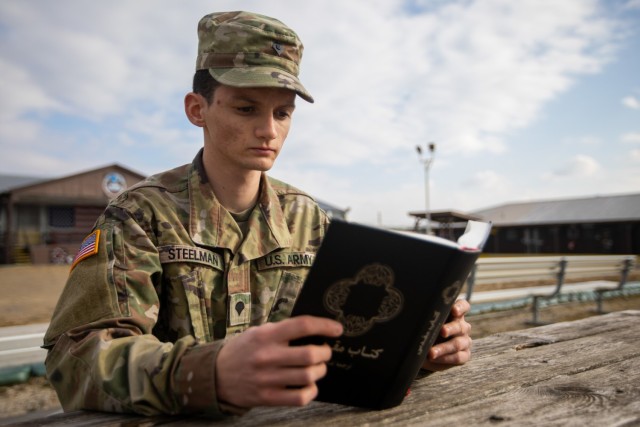

While Latkaitis and Babcock have both learned their languages through immersion into the culture by living in the countries, U.S. Army Spc. Joshua Steelman took a different path.

Steelman joined the Indiana Army National Guard in 2020, and now serves with the Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 76th IBCT, deployed to Kosovo.

Prior to leaving for basic training, Steelman had the opportunity to take the Defense Language Aptitude Battery, which evaluates how well a native English speaker can learn a new language. Questions on the test range from selecting words that have different sounds and applying basic grammar rules to made-up words. Based on their results, applicants are divided into four categories by difficulty to learn. Steelman’s scores placed him in the Category III language: Farsi.

Category I is considered the easiest and shortest course at 30 weeks. It has six languages including Spanish, Italian and French; while Category II has four languages: German, Romanian, and Indonesian. Category III is the largest category, having 28 languages including Polish, Ukrainian, Russian and Farsi, which are learned over 48 weeks. Category IV is the highest level, with languages like Arabic, Chinese, Japanese and Pashto, requiring 63 weeks of learning.

After basic training at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., Steelman was sent to the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center in Monterey, Calif. for 48 weeks to learn Farsi.

“It was intense,” Steelman said, when asked what the training was like. “It was eight hours a day of learning the language with teachers, in the classroom setting and then, in addition to that, we had two hours of homework, so it was a very intensive study of that one language.”

Steelman said the course started with sound and script for the first two weeks, learning the alphabet, the sounds of the language and how to write the script. He said even in the beginning, the students were required to learn 30 new words a day. After the first two weeks, the students went topic by topic beginning with family, food, places of interest.

“There was speaking practice at the end of the day where we participated in made-up scenarios,” Steelman said.

“Through two thirds of the course, one hour each day was dedicated to a new grammar point and towards the end, the topics got a little more complex, like with economics and politics. At the very end [of the course], it was just studying what we felt we needed to work on the most.”

Despite being deployed in Kosovo, Steelman still keeps up with this Farsi however he can.

“I have a Farsi Bible that I read sometimes,” Steelman said. “I listen to the Farsi BBC, and YouTube and there’s some Farsi podcasts and talk shows that I watch.”

Keeping up on a language can be a matter of necessity for individuals with family who speak another language, or, in the case of U.S.Army Spc. Tristan Reed, can’t speak at all.

Reed is Combat Engineer, and also a member Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 76th IBCT, Indiana Army National Guard, deployed to Camp Bondsteel, Kosovo. He grew up with an aunt who was fluent in American Sign Language (ASL) because her parents were deaf.

“I would always go and hang out with them almost every other weekend or every weekend and it just intrigued me to learn more about sign language,” Reed said.

Reed attended high school in Indianapolis, Ind. and needed to take an elective foreign language class to get his core 40 honors. He decided to take sign language due to the new teacher actually being deaf. Reed said he saw this as an opportunity to learn more and be able to surprise his aunt with his knowledge.

“I was very intrigued on learning how it all worked and just learning more about sign language,” Reed said, as he knew nothing of the culture prior to the class.

As with learning any new language, the class started with the alphabet and greetings, before moving on to presentations on signing and getting hands-on practice. Reed said every year the class would put on a concert in sign language during Christmas time.

“I remember my junior year, we did ‘Jingle Bell Rock’ in sign language and her [the teacher] entire deaf community came out as we sang and signed,” said Reed.

Reed still used his skills outside of school when he worked in the local hospital’s cafeteria. He said the nurses knew he could sign and would ask him to help communicate with patients.

“Most nurses would know another language or they would have some type of translator, but they had no one for sign language,” Reed said.

In ASL, knowing the culture and the nuances is critical. Reed said he learned a lot of signing is using your expression and body language when speaking, if you want to be understood.

“The simple fact is when you ‘speak’ in sign language, you have to use expressions and emotions, otherwise the context is lost,” Reed said.

Reed, along with Bartkaitis, Babcock and Steelman, all agree that knowing a second language is invaluable. While being able to communicate in another language is useful, it is the understanding and appreciation of another culture that makes the struggle to learn worthwhile.

“It gives us a different perspective of life overall,” Bartkaitis said.

He said he knows it’s no easy task to learn another language, but with each language a person learns, the more about the culture they can understand.

Steelman said knowing another language helps expand your horizons and understand different views.

“I think it also provides a deeper look into other cultures,” Steelman said. “I learned a lot about it’s [Farsi’s] people, about how they view the world, their perspective on everything, and I think the language really helps with that.”

Social Sharing