REDSTONE ARSENAL, Ala. — Gen. Ed Daly’s Army story is one full of obstacles and possibilities, both of which allowed him to serve in this Profession of Arms for more than 35 years.

Daly grew up a stone’s throw away from New York City in Jersey City, New Jersey. He lived in a diverse neighborhood, supported by his mom, who was a medical transcriber, and his dad, a police officer. While he lived in an environment of high standards, discipline and accountability taught by his father, a former tanker, it did not come without challenges.

“It was tough because there were a lot of temptations and opportunities to stray from doing the right thing,” Daly said.

This is where the “3-5-100” rule first impacted his life. Daly believes everyone has three defining moments, five key decisions and hundreds of influential people who will impact their life.

“The first core part of this was my family,” he said. “They kept me on azimuth.”

Daly remembers a moment when he was off azimuth. One day, his dad took him about six blocks from home to a train station that overlooks the New York harbor, an area known for its Ellis Island transit. He remembers his father asking him, “What are you going to do? Who are you for?”

Daly’s plan was to go to college and to play baseball at the next level. To help achieve the first goal, Daly attended Saint Peter’s Prep, a religious college preparatory school. To afford the tuition, Daly’s dad took on two extra jobs working as a tow truck operator and a warehouse guard.

As for the second goal, Daly was invited to showcase his talents to baseball recruiters, but he was told he didn’t quite have what it took.

Daly found himself considering different possibilities when a friend mentioned they’d talked to a U.S. Military Academy recruiter. He decided to do the same, ultimately deciding to apply to West Point and to the U.S. Naval Academy. His new plan was to accept whichever institution offered him a position first. Luckily, the Army’s acceptance letter came in first, and adjusting to the regimen of military academy life ultimately helped Daly gain a selfless service perspective.

When the time came to start his Army career, he decided to go into ordnance for its marketability. His plan was to serve for five years and transition into the private sector.

He experienced a lot in those early years, including his first exposure to combat during the Gulf War. As a second lieutenant, he was cutting his teeth at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, when the call came to deploy. Three weeks before the ground war, Daly found out his dad was terminally ill.

His dad, whom Daly calls his hero, died in his 50s. Daly was able to take time to be there for his family, but on the day of the funeral, he flew back to Southwest Asia. This moment taught him something he would remember during future deployments.

“It demonstrated to me what it meant to be part of this great Profession of Arms. It isn’t about me,” Daly said. “Leading Soldiers in combat, I realized you really have to set the example. You have to work through internal turmoil.”

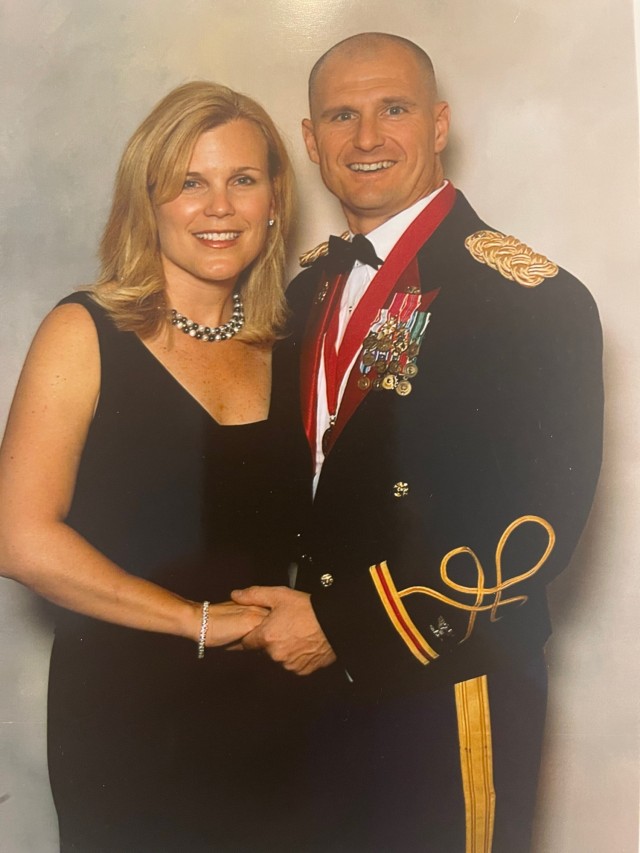

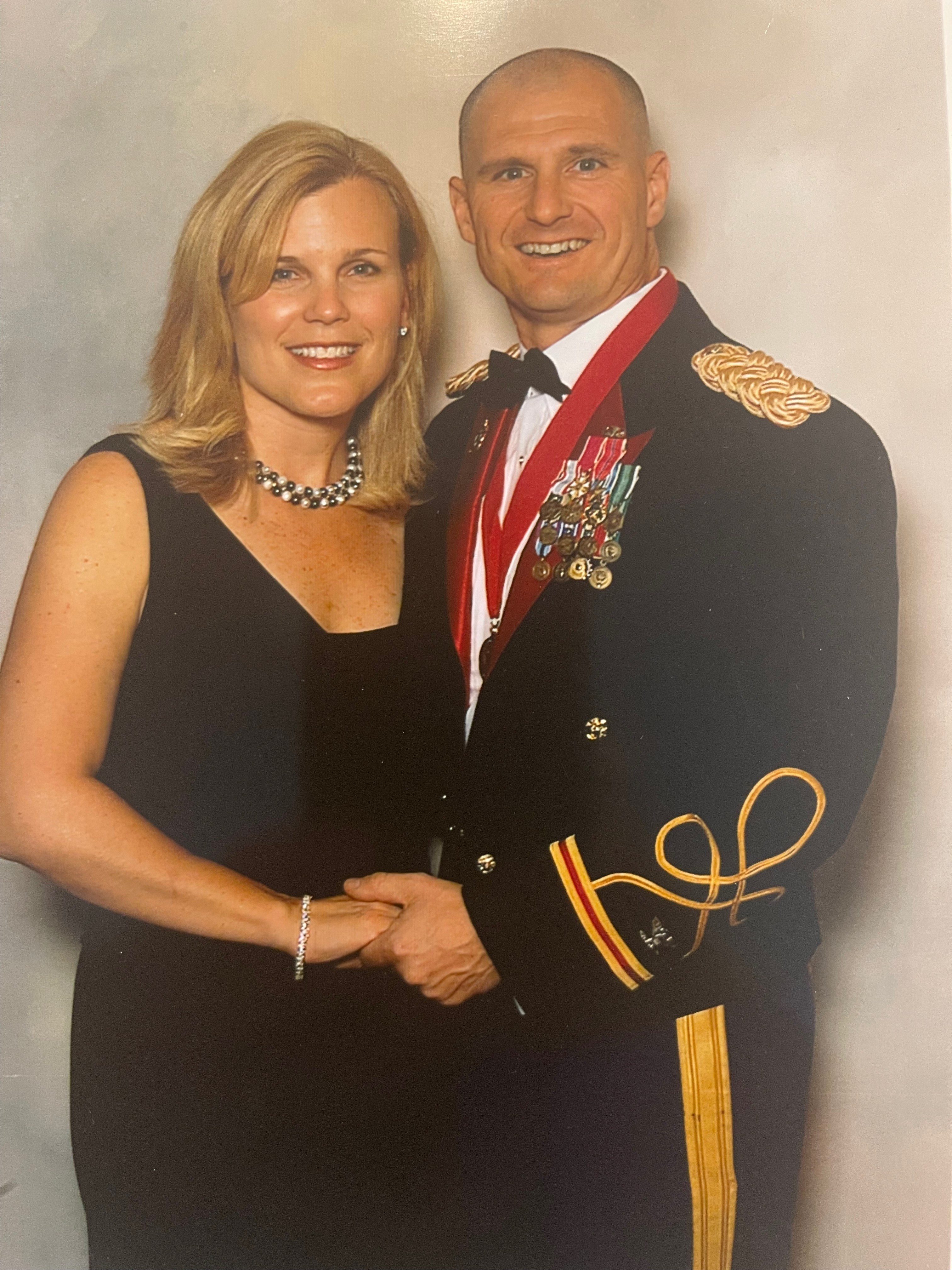

Years later, new possibilities presented themselves. He would meet Cathy while he was serving in Europe as a captain. She was a 1991 West Point graduate who served in the same brigade. The two found themselves at a crossroads when Daly was assigned to Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, and Cathy was assigned to Fort Lee, Virginia — on the opposite side of the country. She decided to separate from the Army, which would later allow her to spend time with their kids in their formative years.

“One thing is for sure, if she stayed in, she would have been General Daly,” Daly said.

For the Daly family, the coming years were filled with assignments — from Korea, to Texas, to Italy — all that had meaningful lessons in leading and learning. One highlight was his golden major years at the 1st Cavalry Division, one that had 36 future general officers. Another highlight was becoming chief of ordnance, about 25 years after choosing the branch at West Point.

“That was a myriad of different emotions,” Daly said. “One being that I never thought I would make that rank.”

These two assignments gave Daly a new perspective as he started understanding all warfighting functions, the balance between operations and logistics, and the three domains of learning.

All of this experience culminated into his time at Army Materiel Command, where he served as the chief of staff, the commander of Army Sustainment Command, AMC’s deputy commanding general and ultimately AMC’s commanding general. Daly said the beauty of AMC is its presence and impact in all 50 states and worldwide.

“Being the Army’s senior sustainer, you have to think about what’s best for the sustainment enterprise,” he said. “What a privilege for me, what an honor for me to still wear the uniform.”

Along with the challenges that come with being the Army’s senior sustainer, Daly’s time in command was met with challenging tasks like the COVID-19 global pandemic, Afghanistan retrograde, improving quality of life for Soldiers and families, modernizing World War II-era organic industrial base facilities and supporting allies and partners.

As he prepares to enter a new phase as a Soldier for life in the next month, Daly has some insight for the next generation of Army leaders: work hard, persevere and dare to be great.

“Make sure your organizations are underwriting setbacks and setting not only a positive, inclusive environment, but one that allows people to feel comfortable going the extra mile,” he said. “As leaders, we’re going to make mistakes, but as long as you’re giving 110%, you have that watch-my-tracer mentality, people will learn from you.”

Social Sharing