SOUTH FORK, Colo. — If you have spent much time on military-related social media platforms, you’ve probably seen some of the memes featuring a seasoned U.S. Army sergeant major with a Master Explosive Ordnance Disposal Badge and Combat Infantry Badge.

The Army EOD technician behind those memes is retired U.S. Army Sgt. Maj. Mike R. Vining, one of the founding members of the U.S. Army's premier Special Mission Unit and one of the unit’s first EOD technicians.

The reason his Army career has gained so much attention is because Vining has participated in many of the American military operations that defined the latter part of the 20th century, as an Explosive Ordnance Disposal technician and an elite Special Forces operator.

Growing up in Howard City, Michigan, Vining was interested in science and mountain climbing. He received chemistry sets for Christmas every year and earned the grand prize in a high school science fair for a Wilson cloud chamber. Vining was also a member of the science club and chess club and participated in wrestling and track.

Vining then watched a movie that changed the trajectory of his life.

“I saw a World War II movie about a British soldier disarming a large German bomb in an underground chamber in London, England,” said Vining. “I thought, wow, that must take a lot to disarm a large ticking bomb.”

At 17, not long after the Tet Offensive in the Vietnam War, Vining went to an Army recruiting office and signed up to be an ammunition renovation specialist with the plan of volunteering for EOD as soon as possible. After graduating from basic training camp at Fort Knox, Kentucky, he went to Ammunition Renovation School on Redstone Arsenal, Alabama, where he learned how to destroy unserviceable code H ammunition during a course that was taught by EOD technicians.

He attended EOD training on Fort McClellan, Alabama, and Indian Head, Maryland, and graduated in May 1969.

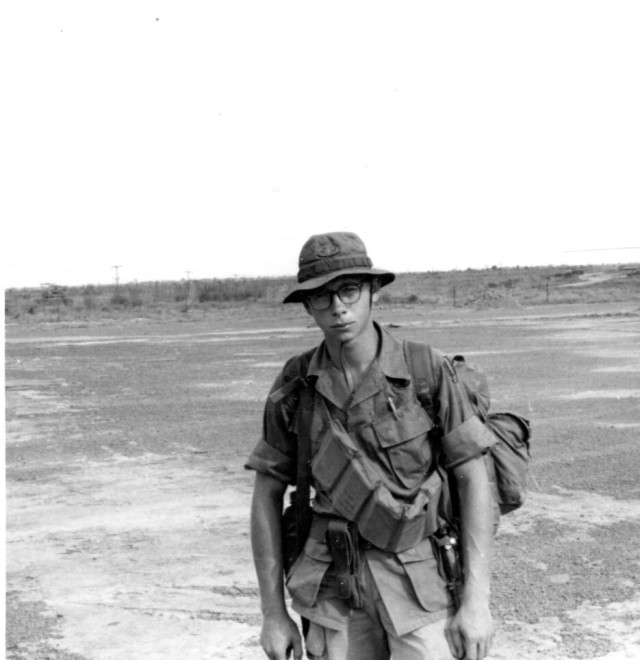

While serving with the Technical Escort Unit at Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland, he volunteered to serve in Vietnam and he spent 11 months with the 99th Ordnance Detachment (EOD) in Phuoc Vinh, Vietnam, in an area west of Saigon and near the Cambodia border.

Two of the most memorable EOD operations of his career happened in 1970 when he participated in the destruction of the Rock Island East and Warehouse Hill enemy weapons and ammunition caches in Cambodia.

Vining was part of the seven-man Army EOD team that supported the 1st Cavalry Division mission to secure and destroy the largest weapons and ammunition cache discovered during the U.S. military’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

Named Rock Island East after the Rock Island Arsenal in Illinois, the enemy weapons cache had 932 individual weapons and 85 crew-served weapons as well as 7,079,694 small arms and machine gun rounds. The enemy cache also contained almost a thousand rounds of 85mm artillery shells that were used for the D-44 howitzer and the T-34 tank.

Vining and the EOD techs had to dodge enemy fire and endure biting red ants while working on the cache. After setting up “scare charges” to keep enemy forces out of the security perimeter, Vining made it on the helicopter in time to watch the explosion and see the mushroom cloud that was visible from 50 miles away. The seven Army EOD technicians at Rock Island East used 300 cases of C4 explosives to destroy 327 tons of enemy munitions.

During the operation to seize the cache site, 10 American Soldiers died and 20 were injured.

Later at the Warehouse Hill operation in Cambodia, the EOD team had to disarm booby traps and crawl into underground tunnels to place C4 explosives on 14 cache sites. Vining had to contend with large cave crickets, poisonous centipedes, spiders, bats and scorpions in the narrow tunnels. The teams used 120 cases of C4 explosives to destroy hundreds of thousands of enemy rounds.

After completing his tour in Vietnam, Vining left the Army and returned home to Michigan. He got a job at a plant that stamped out automotive body parts for Ford Motor Company and then became the lead employee on the third shift of the largest press in the plant, a 500-ton press.

“Although it was very good pay, I did not see myself doing this for 20 to 30 years,” said Vining. “In October of 1973, I saw my Army recruiter and asked to go back into the Army.”

The U.S. Army recruiter told Vining that he would have to serve as an EOD technician again, which was exactly what he wanted. He was assigned to the 63rd Ordnance Detachment (EOD) on Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri.

Vining was serving on a U.S. Secret Service support mission when his EOD supervisor, Sgt. Maj. Kenneth Ray Foster, Sr., was killed by an improvised explosive device at the Quincy Compressor Division Plant in Illinois, in 1976. Afterward, Vining thought it was time for a change.

“I decided to take emergency medical technician training and following that I decided to volunteer to be a Special Forces medic,” said Vining. “I was getting out of EOD when my control sergeant major told me that they were forming a new Special Forces organization at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and that they were looking for six EOD techs.”

Vining called the number and flew to Fort Bragg for an interview with Col. “Chargin’ Charlie” Beckwith, the founder of the premier Special Mission Unit. Beckwith envisioned the concept that the U.S. Army should have a counterterrorism unit like the British Special Air Service.

“Two weeks later, I was one of four Army EOD techs to start the Operator Training Course 1,” said Vining. “Only two of us made it through. The second person was retired Sgt. Maj. Dennis E. Wolfe.”

One of the unit’s first operations was the clandestine mission to rescue 53 American hostages at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran. Known as Operation Eagle Claw, the rescue mission was cancelled after the loss of three helicopters during a sandstorm at the staging site known as Desert One.

While the aircraft were leaving the Desert One staging area, a RH-53D helicopter crashed into the transport aircraft that Vining and his team was on. The helicopter rotor chopped into the top of the fuel-laden aircraft and a fireball shot by Vining and his team.

As the EC-130E “Bladder Bird” was engulfed in flames and munitions cooked off around them, Vining and his teammates made it off the aircraft. Vining and his team got on another aircraft with faulty landing gear and just enough fuel to make it across the water to safety.

During the Desert One aircraft collision, eight American troops were killed and both aircraft were destroyed.

Joint Special Operations Command was created as a result of the investigation that followed the ill-fated rescue mission.

In October 1983 during Operation Urgent Fury, when U.S. forces invaded the Caribbean Island of Grenada following the pro-Cuban coup there, Vining was on a rescue team sent to free political prisoners at the Richmond Hill Prison.

His Blackhawk helicopter came under intense enemy anti-aircraft fire on approach to the prison facility and the mission had to be delayed.

The political prisoners were released before a second mission was launched.

After seven years of serving with distinction in the unit, Vining accepted an assignment with the 176th Ordnance Detachment (EOD) on Fort Richardson, Alaska. He made the move to be more promotable within the EOD community and to be close to the mountains of the 49th state.

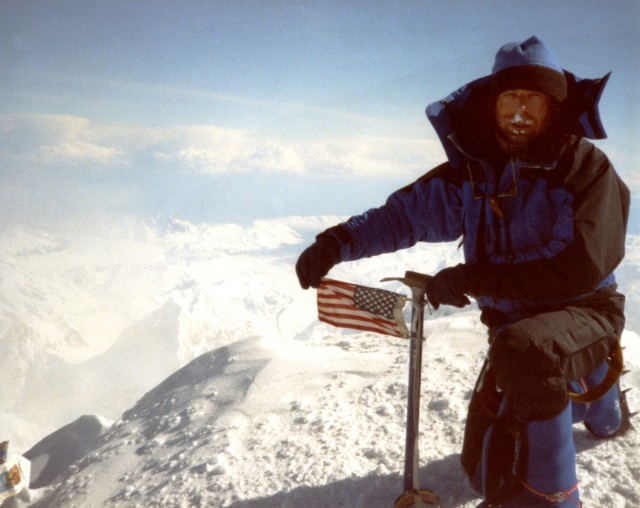

While in Alaska, he maintained his proficiency for EOD missions and later came back to twice climb the 20,310-foot Mount Denali, the highest mountain in North America.

Within one year, he was back at the Special Mission Unit, where he would serve in Operation Desert Storm. Although his EOD duties didn’t change, Vining switched to infantry during this time to make himself more promotable within the elite Special Forces unit.

During this second Special Mission Unit tour, Vining also participated in Operation Pocket Planner during a Federal Penitentiary prison riot in Atlanta in 1987.

Vining would later serve at the Joint Special Operations Command as an exercise planner and J-3 Special Plans sergeant major. He was the Joint Special Operations Task Force senior enlisted advisor aboard the aircraft carrier USS America (CV 66) during Operation Uphold Democracy in Haiti.

The sergeant major also served as an explosive investigator on the task force that investigated the 1996 Khobar Tower bombing in Dharan, Saudi Arabia, and he used the lessons learned from that attack to help hardened U.S. installations around the world.

During nearly three decades in uniform, Vining earned the Combat Infantry Badge, Master Explosive Ordnance Disposal Badge, Parachutist Badge, Military Free Fall Parachutist Badge and Austrian Police High Alpine “Gendarmerie-Hochalpinist” Badge.

Vining racked up a huge stack of medals and ribbons that include the Legion of Merit Medal, Bronze Star Medal, two Defense Meritorious Service Medals, Army Meritorious Service Medal, Joint Service Commendation Medal, Army Commendation Medal, two Joint Service Achievement Medals and the Army Achievement Medal. He also earned his Bachelor of Science Degree in Sociology from the University of the State of New York.

Vining said he was glad when the U.S. Army established the 28th Ordnance Company (EOD Airborne) to support U.S. Army Ranger and Special Forces missions around the world, as well as the two Airborne Platoons of the 722nd Ordnance Company (EOD) and 767th Ordnance Company (EOD) to support the 82nd Airborne Division’s Immediate Response Force mission.

The Fort Bragg, North Carolina-based companies are all part of 192nd EOD Battalion, 52nd EOD Group and 20th Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, Explosives (CBRNE) Command, the U.S. military’s premier all hazards command.

Vining said that the Kirtland Air Force Base, New Mexico-headquartered 21st Ordnance Company (EOD WMD) was another welcome addition to the U.S. Army EOD units. The highly specialized company is part of the 71st EOD Group and 20th CBRNE Command.

From 19 bases in 16 states, Soldiers and U.S. Army civilians from 20th CBRNE Command take on the world’s most dangerous hazards in support of joint, interagency and allied operations.

“In my time, Army EOD was viewed as combat service support, but in reality, Army EOD is combat support and has always been that way and that means supporting Special Operations and Airborne forces,” said Vining.

Vining said the key to success in the EOD profession is noncommissioned officer leadership and mentorship.

“Mentorship is one of the duties of a senior NCO,” he said.

The Army EOD community marked its 80th anniversary in 2022 and NCOs have played a critical role in the EOD profession since its inception. Led by noncommissioned officers, EOD teams often serve on their own in austere environments, covering vast operational areas.

Vining also encouraged EOD techs to seek help for both the seen and unseen scars of war that come with the profession.

“I believe if you spend a career in EOD that you will witness severe injuries and death,” he said. “EOD is an inherently dangerous career, but it is also a very rewarding career knowing you have eliminated a hazardous situation.

“If you are suffering from events that you were involved in, you are not alone in dealing with this kind of trauma. I encourage you to open up and just talk about it to a fellow EOD tech or an EOD veteran,” said Vining. “From World War II to the present, we have all witnessed the horrors of war and even the dangerous job we do in peacetime.”

In January 1999, Vining retired from the U.S. Army and married his wife Donna Ikenberry, a hiking guidebook author, professional wildlife photographer and freelance photojournalist. They were engaged at the top of Mount Rainer in Washington and exchanged wedding vows on Mauna Kea, the highest mountain in Hawaii.

Today, they live together in South Fork, Colorado, where Vining continues to enjoy spelunking, skiing, rock climbing and mountaineering. He also remains active in the veteran’s community.

Vining was inducted into the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps Hall of Fame in 2018.

When he hung up his highly decorated uniform after nearly three decades of service, Vining said he never knew that his storied career would later launch a tidal wave of memes.

“I do not know how any of the memes got started,” said Vining. “One of my grandchildren saw that someone even did a Pokémon card on me.”

Social Sharing