Few World War II campaigns are as forgotten as the 14-month effort to expel Japanese forces from the Aleutian Islands from June 1942 to August 1943. Then part of the Territory of Alaska, the Aleutians stretch across the Bering Sea and could be used strategically to hamper any possible U.S. attack on Japan across the Northern Pacific or to threaten home-front Americans from bomber bases within range of major West Coast cities like Anchorage, Seattle, San Francisco or Los Angeles.

The campaign involved land and sea forces of the United States and Canada. Besides geography and weather, these allies had to overcome good defensive strategy and fierce resistance that enabled the Japanese to stave off a much larger force for an unexpectedly long time. However, Japan failed to secure Dutch Harbor on Unalaska Island and a naval engagement off the Komandorski Islands blocked Japanese surface resupply of its occupation forces on Attu and Kiska islands, signaling ultimate defeat.

Allied forces, including regiments of the 7th Infantry Division, deployed from Fort Ord and landed at Attu on May 11, 1943. After three weeks of difficult fighting, the Japanese launched one of the war’s most horrific banzai charges – a “fight to the death” attack that ended in brutal hand-to-hand combat, collective suicides, and left only a few Japanese soldiers alive to be interrogated by the 7th’s Nisei linguist detachment. The attack was so traumatizing that the Army bombed Kiska Island for nearly three weeks prior to invading it next, despite intelligence indicating that Japanese forces had already abandoned the island. During that invasion, American and Canadian troops mistook each other for the enemy, leading to numerous friendly fire deaths. Less disastrously, the Navy attacked a mysterious group of enemy warships after technicians using a new technology called radar detected strange signals … later thought to be a flock of birds.

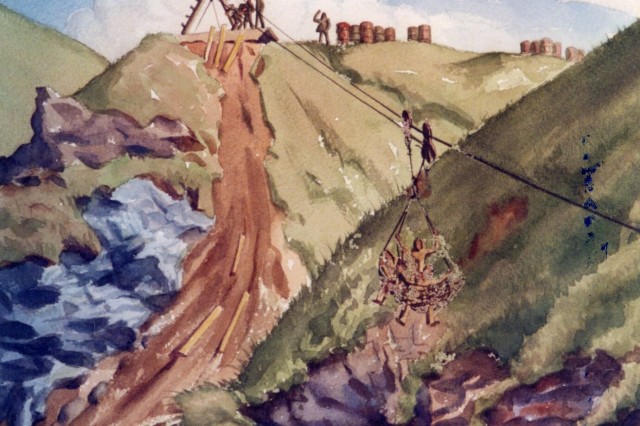

One of the biggest challenges for both sides was the remote environment, rugged terrain, and challenging weather of the Artic region. To help tackle these problems, the Army organized a platoon of Alaskan Scouts composed of outdoorsmen who could conduct reconnaissance and live off the land. It also deployed cartographers to help map the landscape and guide Army efforts.

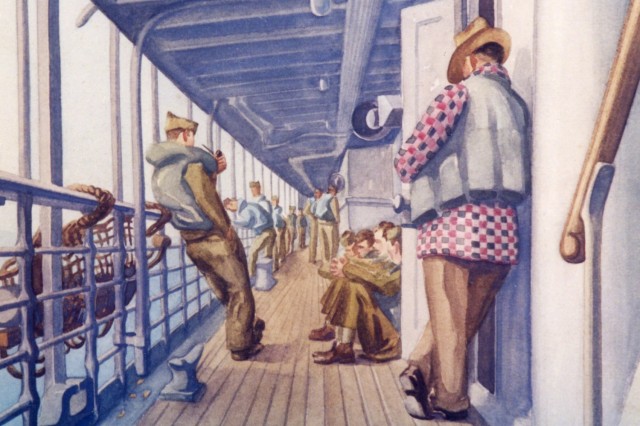

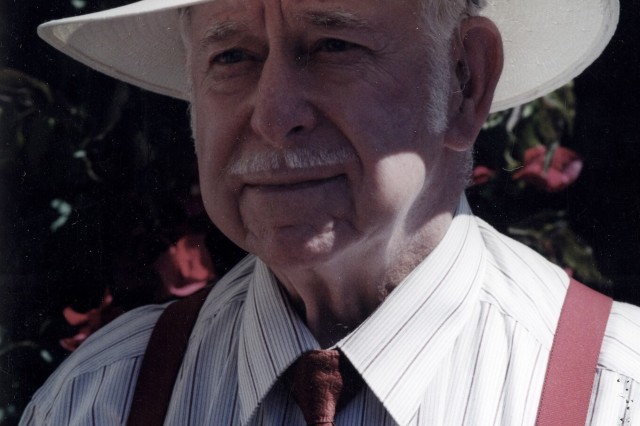

One of the Army’s mapmakers was Ernie Hardenstein, who deployed from Fort Ord to Attu in 1943 with the 7th Infantry Division and returned in 1944 after completing photo interpretation training at Camp Richie, Maryland. Having studied at the Delgado Trade School and the New Orleans Art Academy before the war, Hardenstein documented his wartime experience in the Aleutians by composing numerous drawings and watercolors. Demobilized in 1946, Hardenstein settled near Fort Ord and continued to make a living as a painter. In 1997, the Fort Ord Alumni Association organized a showing of Hardenstein’s wartime work at the Stilwell Community Center in Seaside, California, called “From Fort Ord to the Aleutians, 1942-1944” from which the images shown here are derived. Hardenstein died in 2007 at the age of 92.

Across time, combat artists have made a lasting impact by capturing people, places and events that can elude photojournalism. Inherently a malleable medium, fine art lends itself to storytelling and can visualize history with less trauma than photography, allowing the interpretive power of the artist’s hand to communicate without words messages that can help teach and heal while grappling with feelings or ideas that are often difficult to express. Recognizing this tradition, the U.S. Army Center of Military History maintains the U.S. Army Combat Artist Program, which you can learn more about at https://www.history.army.mil/museums/armyArtists/index.html

Social Sharing