FORT LEE, Va. - It was observational learning, I think, that helped me understand how to conduct myself on social media as a public servant.

I was finding my legs on Facebook in 2010 while deployed to Iraq. There was a comical video circulating around our offices in Baghdad and on social media depicting young, uniformed Middle Eastern men lined in a row attempting to perform jumping jacks. Some looked to be freestyle dancing and all seemed incapable of mimicking the movements of U.S. service members opposite them and in-the-lead as instructors.

As a public affairs noncommissioned officer, I was writing stories about the start of Operation New Dawn, taking extra care to include command messages on how capable and ready Iraqi Security Forces were to build a safe, secure and sovereign country. It was the antithesis to the dilemma of U.S. advisors in the country sharing a video titled “Iraqi cadets can’t do jumping jacks,” with a subtitle of “Oh boy, we’re going to be here for a while.”

I wondered how that communication might be received by Iraqis. What would the American taxpayer say? In what ways would a video of this sort potentially impact the mission?

My general feeling was that while this was a light-hearted video and could be viewed as harmless, the idea of Americans laughing at their Iraqi counterparts ran counterproductive in ways to what we were attempting to accomplish and, therefore, should not have been shared by those sworn to the mission.

For the record, I can say with certainty that young Middle Eastern men are fully coordinated and capable of mastering athletic skills far beyond jumping jacks. That lesson was driven home during several Iraqi versus American soccer matches I jumped into during that deployment. The Iraqis almost always won.

Still, there was a stigma we were working to overcome— an idea that Iraqi security forces were less than capable.

As well, we were working to overcome stigmas of our own, especially in the aftermath of the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse photos released on the internet.

SOCIAL MEDIA IS A POWERFUL TOOL

Recognizing the potential drawbacks of undisciplined social media conduct, the Army published guidance in March 2017 that became known as the “Think, Type, Post” Memorandum. The acting Secretary of the Army, Chief of Staff and SMA demanded that Soldiers:

“Think” about the message being communicated and who could potentially view it now and for years to come; “Type” a communication that is consistent with Army Values; and “Post” only those messages that demonstrate dignity and respect for self and others.

Aside from “thinking” appearing in the memo as a separate activity from the physical exercise of writing, the thing that stands out most to me is the directive that Soldiers should first consider how communication is both omnidirectional and diachronic. The sender’s message could reach anyone, not just their immediate social media friends, and at any future period of time, not just the number of hours it appears in their friends’ feeds per the social media platform’s algorithm.

We know security and OPSEC are issues of concern when it comes to social media. Consider, for example, how a near-peer adversary might exploit a post to amplify divisive content and/or disseminate false narratives in order to undermine democracies, divide societies and weaken alliances.

Thus, for a mature organization like the U.S. Army, this is all a matter of force protection, stability maintenance and reputation management.

WITH GREAT POWER COMES GREAT RESPONSIBILITY

It is natural that people want to use social media to speak their minds in an attempt to influence the world, and it is subsequently natural that the hierarchy they fall under wants to wield influence on what their people say for the sake of the organization, its people and its stakeholders.

The “Think, Type, Post” initiative can be thought of as an effort by the Army to help its members make good decisions while it works to self-sustain as an organization. It’s the framework for discussions about the left and right limits of social media conduct and the constitutional purpose of those parameters.

A timely example, with mid-term elections happening this month, is the restrictions government personnel must be mindful of as they are engaging in online communication. The Hatch Act of 1939 – a law to “Prevent Pernicious Political Activities” – prohibits federal civil service employees from using their official authority or influence in political activity. They are restricted from fundraising or campaigning for a candidate while on duty or in a manner that connects them to their government position. The act also precludes federal employees from membership in “any political organization that advocates the overthrow of our constitutional form of government.”

Identical restrictions for uniformed personnel are outlined in Department of Defense Directive 1344.10, “Political Activities by Members of the Armed Forces.”

PRESERVING THE TRUST OF THE AMERICAN PEOPLE

After it became known that current service members were present at the Jan. 6 insurrection, Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III led a campaign to root out extremism in the force.

The reissue of DOD Directive 1325.6 in December 2021 is part of that effort. Rallying on behalf of an extremist group or “liking,” reposting or otherwise distributing extremist views on social media are identified as prohibited activities.

I am proud to work for an organization that wants to make things right as best it can and enacts policies against scourges on society like extremism and cyber bullying.

In 2015, an All-Army Activities (ALARACT) bulletin defined online misconduct as “the use of electronic communication to inflict harm.” Cited examples include “harassment, bullying, hazing, stalking, discrimination, retaliation, or any other types of misconduct that undermine dignity and respect.”

My belief is that DOD employees have a responsibility to report online misconduct. We are stewards of our organizations’ reputations. If the report is valid and a service member or civilian employee is disciplined for bringing shame to the armed forces, it proves our policies and systems are working.

When a service member or DOD civilian, though, exercises his/her 1st Amendment right and expresses his/her opinion on an issue of import, especially in defense of the reputation of one's service branch, and that service member or civilian is condemned by his/her organization for bringing “a measurable amount of negative publicity” to his/her branch when I see nothing in the message outside the left/right limits, well, it leaves a bad taste in my mouth.

All I can say in response is that we have to be careful what we say and in what capacity we say it, whether that be official or unofficial.

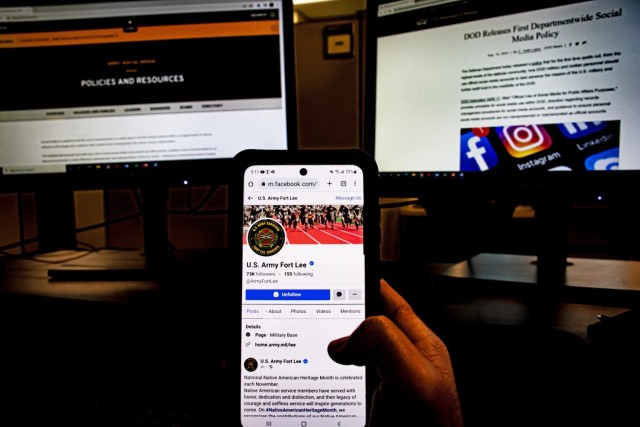

THE LATEST DOD GUIDANCE

In the newest ALARACT bulletin (dated Oct. 27, 2022) the Army supplemented its social media policy, expanding guidance on how DOD employees should handle their personal versus official individual accounts.

The policy reads, “DOD Personnel must not use personal social media accounts for official purposes of conveying DOD information or official DOD positions.”

Official information may be forwarded, liked or otherwise linked to an official source, though.

The Army continues work toward protecting its people from real or perceived misconduct and maintaining a clear detachment from politics.

As a precaution, social media users are advised to remove specific information from their personal social media accounts that identifies them as a DOD employee. Rank and/or official duty titles, for example, should not be used with unofficial, personal accounts.

This distancing and detachment practice reminds me of when I was a high school English teacher, and we were advised to create official social media accounts for the purposes of information dissemination, public relations and engagement with parents. We were further instructed to create a profile name/handle other than our actual identities, in part, so that we were not searchable by students.

One administrator told us to have a friend or family member snap a picture of us drinking from a milk carton in front of our refrigerator, a wholesome image that, as he put it, students and/or parents would see as trustworthy, harmless and positive. There’s a possible lesson to be learned there; overlooking the fact, of course, that drinking directly from the carton can be seen as unsanitary.

The idea is that you portray yourself officially as neutral and decent for the sake of the organization. Which brings us back around to the gist of my argument that a public servant should take the opportunity to act on social media as a steward to his/her organization’s reputation AND be allowed to practice his/her constitutionally protected right on social media to democratically express himself/herself.

Yes, as long as that conduct is “consistent with Army Values.”

By most composite measures, the United States Army owns a reputation – worldwide and historically – as the best, most powerful, strategically responsive, highly trained and technologically advanced of armies.

It might seem strange, then, to some that I have mentioned a need for reputation management throughout the commentary, but I would like to remind those persons that every organization in the history of humankind has had a beginning, middle and end.

Reputation and the communication surrounding an organization’s reputation matter greatly. The idea that communication creates, maintains and destroys organizations is a bedrock for every major communication theory alive today.

Let us stand true to our country’s founding principles, then, in our social media conduct and be just in our policies on that conduct.

Long live the U.S. Army and the constitutional liberties it protects.

Social Sharing