By Cameron Binkley

DLIFLC Command Historian

It was July 7, 1846, and the Mexican American War was in full swing. On that Tuesday morning, a small force of U.S. Sailors and Marines landed on a narrow beach near the Mexican government custom house at Monterey Bay. Meeting no opposition to their arrival in Monterey, the old Spanish colonial capital, the Americans quickly secured the town, hosted their flag, and took possession of California for the United States.

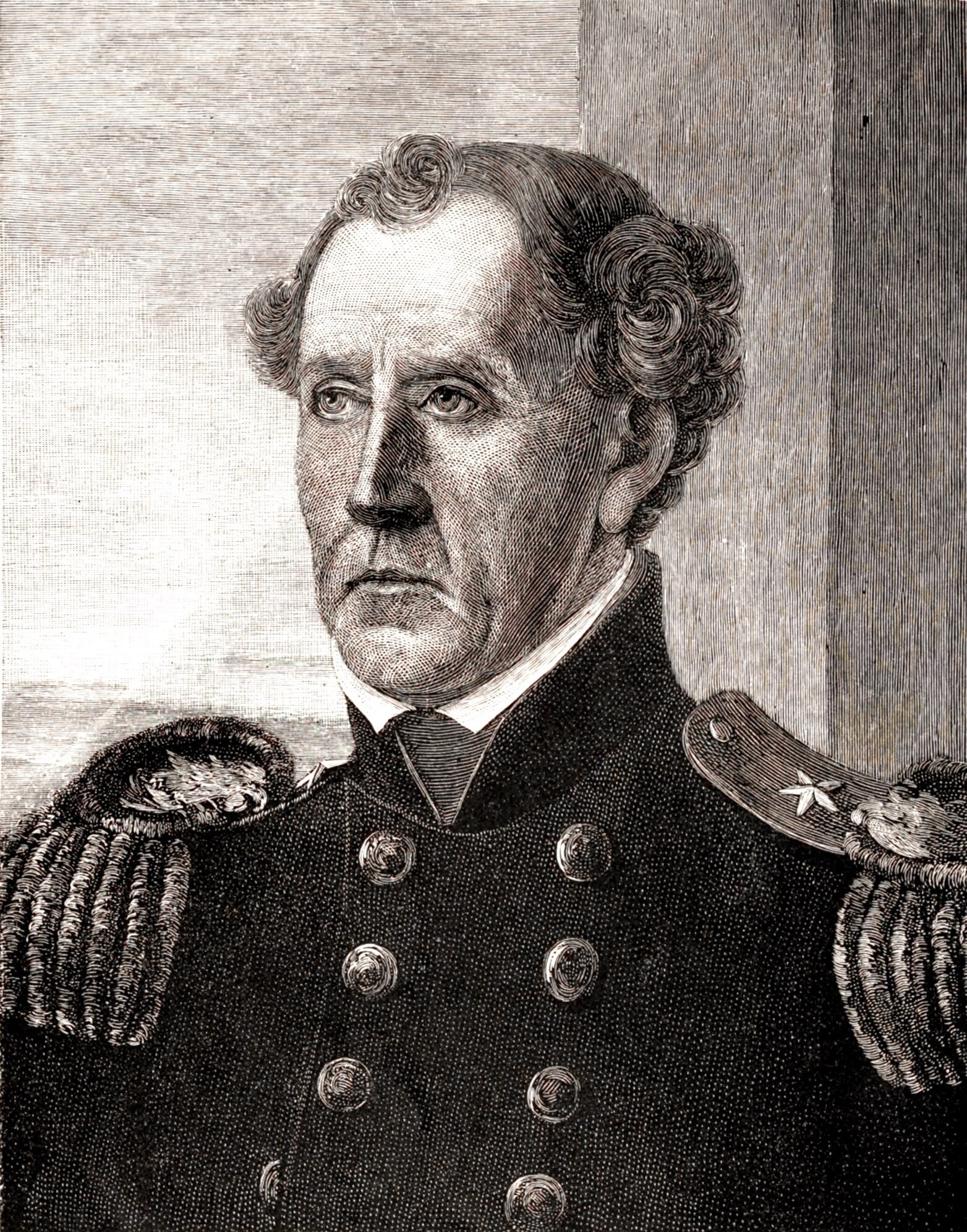

The man in charge of the operation was Commodore John D. Sloat. Having made the critical decision to occupy Monterey (on sketchy intelligence), Sloat next sent his commanders to secure California’s other main ports and issued an important proclamation to its citizens assuring them that their rights and privileges would continue unadulterated under American administration, limiting the spread of insurrection. When ratified under terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, Sloat’s actions (and the successes of other commanders) extended U.S. boundaries westward from the Rockies and the Rio Grande River in New Mexico to the Pacific Ocean.

After only a few weeks in Monterey, Sloat rotated from command as scheduled. The next commodore in charge of California was Robert Stockton, who became more famous for his actions while serving as military governor. Indeed, many who served in California during the war later became famous, including John C. Fremont, William Tecumseh Sherman, Edward O. C. Ord, and Henry Halleck. But historical prominence eluded Sloat.

At the 40th anniversary of the raising of the U.S. flag in California in 1846, veterans of the Mexican American War, led by Edwin Sherman, a Mason and war veteran from Oakland, California, launched a movement to memorialize Sloat. They decided to erect a monument on “Fort Hill” in Monterey at the spot where Sloat’s men had constructed harbor defenses. Their campaign began in 1886 and concluded with a dedication ceremony in 1910 attended by many hundreds. To facilitate donations, donors were allowed to inscribe messages on the base stones of the monument that today say as much about the social history of the era as the political events the monument itself commemorates. For example, three blocks were donated by women’s organizations denoting the new role of women in civic life.

Promoters of the Sloat Memorial hoped it would become the first monument of national stature erected on the West Coast. The cornerstone was laid during the 50th anniversary celebrations of the raising of the U.S. flag in California in July 1896. Unfortunately, fund-raising progress was slow. Before the monument could be completed the United States fought another war, this time with Spain. That war resulted in Commodore George Dewey’s victory over the Spanish fleet at the Battle of Manilla Bay in 1898 and eventual U.S. annexation of the Philippines. To celebrate a new war hero, San Francisco erected the Dewey Monument at Union Square, which was dedicated in 1903 by President Theodore Roosevelt. Having lost their race, the Mexican War veterans faced another setback when the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 destroyed the studio of Rupert Schmid, the Sloat Memorial’s sculptor, and seriously crimped Sherman’s ability to raise funds. With their population ever shrinking, Mexican War veterans convinced Congress to authorize limited funding and the War Department approved a small war eagle by artist Arthur Putnam to replace a more grandiose statue planned by Schmid.

Although it took years to create the Sloat Memorial, the monument has stood the test of time, becoming one of the most widely photographed attractions in Monterey. Indeed, countless veterans, servicemen, and graduating classes of the Defense Language Institute have selected the venue for their photos. Those wishing to visit the monument can easily do so by accessing the lower Presidio of Monterey, an area managed as a historical park and open to the public year-round.

Social Sharing