ABERDEEN PROVING GROUND, Md. – America has a sleeping problem – and for many service members, it’s even worse.

- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a third of U.S. adults report they usually get less than the recommended amount of sleep, which is seven to nine hours for adults 18 – 64.

- The Army Public Health Center’s 2021 Health of the Force report says only 38 percent of Soldiers attained seven or more hours of sleep during the work/duty week, and 10 percent reported getting less than four hours of sleep.

- A March 2021 Pentagon report on the Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Readiness of Members of the Armed Forces said inadequate sleep for service members was more the rule than the exception, and about double what is being reported for civilian populations.

The Army identifies sleep as a critical part of the Performance Triad of sleep, activity and nutrition as well as a key element of Holistic Health and Fitness or H2F.

The bottom line, according to the March 2021 sleep deprivation report, is inadequate sleep “negatively impacts a Service member’s military effectiveness, evidenced by a reduced ability to execute complex cognitive tasks, communicate effectively, quickly make appropriate decisions, maintain vigilance, and sustain a level of alertness required to carry out assigned duties.”

Lack of adequate sleep can also contribute to poor health outcomes.

The CDC says not getting enough sleep is linked with many chronic diseases and conditions—such as Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, obesity and depression. It has also been a contributing factor in motor vehicle crashes and machinery-related injuries, causing substantial injury and disability each year.

Dr. Sara Alger, a sleep research scientist at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research Behavioral Biology Branch's Sleep Research Center in Silver Spring, Maryland, said some studies comparing lack of sleep with Blood Alcohol Concentration find that when a person has 24 hours of continuous wakefulness or if they only get four hours of sleep over five to six nights, they’re operating at a performance-level equivalent of a .09 blood alcohol level. The legal limit of intoxication in the U.S. is .08 BAC, so going to work under this level of sleep loss looks similar to going to work drunk, which can lead to increased risk for accidents, injuries, and other fatigue-related consequences.

Some service members out there might be saying getting the right amount of sleep is all well and good, but duty comes first and they have a mission to meet.

One potential solution that is getting increasing attention from the military has been coined tactical napping.

“Some folks will use ‘tactical nap’ in substitution for the concept of a ‘power nap’, which is generally thought of as a 20-minute nap,” said Alger. “We at WRAIR in the Sleep Research Center and our Operational Research Team are not necessarily referring to a duration of a nap when we speak of tactical napping, but rather the intentional use of a nap in order to purposefully better your health, alertness, emotions, and cognitive abilities.”

Alger identifies some specific reasons for the tactical nap. It can be used to:

- To maintain healthy sleep duration and achieve the recommended 7+ hours of sleep per 24 hours that is necessary for maximal health and performance

- To bank sleep before a period of unavoidable sleep loss (e.g., pre-mission) to help pay down sleep debt and sustain performance during that sleep loss

- To grab whatever sleep possible during continuous or extended operations, where longer consolidated sleep is not possible, to help sustain or restore performance

- To recover performance and alertness more quickly following sleep loss

Alger is currently the primary investigator in a multi-study project to determine strategies using the intentional combination of nocturnal sleep and daytime napping to overcome fatigue and maximize cognitive performance and improve mood and emotion regulation.

“We understand that obtaining sufficient sleep underlies your ability to perform physically, cognitively, and emotionally,” said Alger. “Yet, there is often only limited opportunity to obtain a single, sufficiently long consolidated period of sleep of 7+ hours in the operational context.”

Alger said a Soldier’s sleep is often disrupted by arousing environmental factors that reduce sleep quality. Therefore, one consolidated sleep period may not be an ideal sleep strategy for Soldiers to overcome fatigue and optimize cognitive performance and alertness. She is currently working on an in-lab study to compare participants who follow a sleep strategy where they obtain six hours of overnight sleep only to participants who are splitting sleep and using the intentional combination of overnight sleep (4 hours) and either one (2 hour) or two (1 hour each) daytime naps.

“Importantly, all of the participants will be getting the same amount of total sleep, so this study will tell us if there is a strategy that emerges as more effective for better performance or if all strategies seem to be equal,” said Alger. “These results will give us the ability to give more specific recommendations for Soldiers and Leaders in the field regarding how they should try and intentionally incorporate sleep into the daily battle rhythm, when they have the ability to do so, and perhaps make it more acceptable to intentionally nap for the good of Soldier health and performance.”

Alger says she hopes to address some of the stigma and misinformation behind the concept of napping with this project. This is something she has been passionate about for some time.

In a 2019 Letter to the Editor of Sleep, an academic journal published by the Sleep Research Society, Alger and her colleagues argue there is a wealth of evidence that brief daytime naps of 10–20 minutes decrease subjective sleepiness, increase objective alertness, and improve cognitive performance. They also facilitate creative problem solving and logical reasoning, boost the capacity for future learning and consolidates memories.

The letter further points out that daytime napping is “being integrated into workplace culture in the world’s largest grossing tech, consulting, media and retail companies: Google, Uber, Nike, Cisco, Zappos, Huffington Post, PricewaterhouseCoopers, Proctor & Gamble, and Ben & Jerry’s. Not only do these companies encourage workplace naps, but they provide accommodations, such as rooms secluded for the purpose of napping, often equipped with nap pods or beds.”

Alger says Army leadership can start moving in this direction by incorporating two critical components of sleep leadership:

- Managing Soldiers in a way that builds awareness of the importance of sleep, optimizes sleep, and reduces ongoing fatigue.

- Leading by example.

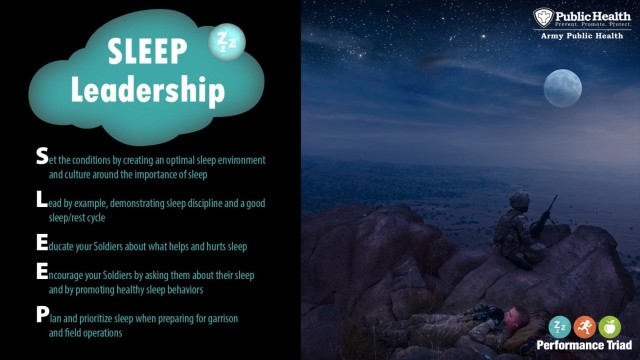

Alger also encourages Army Leaders to practice these five SLEEP Leadership skills, which are also outlined in the in Army Field Manual 7-22, Holistic Health and Fitness:

- Set the conditions by creating an optimal sleep environment and culture around the importance of sleep

- Lead by example, demonstrating sleep discipline and a good sleep/rest cycle

- Educate your Soldiers about what helps and hurts sleep

- Encourage your Soldiers by asking them about their sleep and by promoting healthy sleep behaviors

- Plan and prioritize sleep when preparing for garrison and field operations

The military may have a sleeping problem, but there are a host of resources for Soldiers and Leaders who are trying to improve their sleep hygiene. Here are some of the best:

- WRAIR Sleep Resources

- Peformance Triad: Effective Sleep Strategies

- Health.mil: Sleep

- CDC: Sleep and Sleep Disorders

The Army/Armed Forces Wellness Centers also have health coaches and sleep education services for Soldiers, Army and DOD civilians and their families, including general information about healthy sleep habits, impact of sleep on health and wellbeing, tools, tips and positive action steps to improve sleep.

The Army Public Health Center enhances Army readiness by identifying and assessing current and emerging health threats, developing and communicating public health solutions, and assuring the quality and effectiveness of the Army’s Public Health Enterprise.

NOTE: The mention of any non-federal entity and/or its products is for informational purposes only, and not to be construed or interpreted, in any manner, as federal endorsement of that non-federal entity or its products

Social Sharing