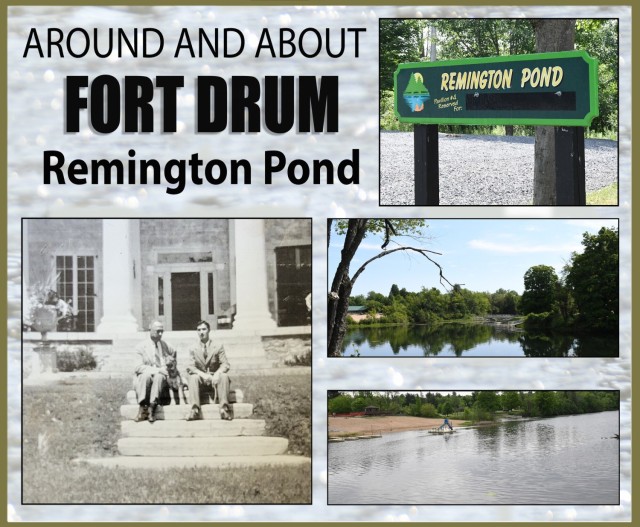

FORT DRUM, N.Y. (July 28, 2022) -- Remington Pond is named after a North Country native and World War I veteran who saved LeRay Mansion from ruin, only to lose it during the Pine Camp expansion in the 1940s.

Harold Remington was born March 3, 1884, in Watertown, to Edward and Helen Remington, the oldest of five children. He graduated from Watertown High School in 1906 and then continued his studies at Amherst College, where he was a member of the Delta Upsilon fraternity.

At age 24, Remington enlisted in the New York National Guard. He was assigned to C Company, 1st Infantry Regiment, at Madison Barracks in Sackets Harbor. This was a year after the first military maneuvers were conducted in the Pine Plans reservation (later to be named Pine Camp).

He married Margaret Havens on Oct. 20, 1910, at Newton Centre, Massachusetts, and their first son, Peter, was born Nov. 4, 1911.

That same year, Remington was promoted to battalion sergeant major. He separated from service with an honorable discharge on Oct. 21, 1912.

Remington was employed with the Kamargo Supply Company, which dealt with mills supplies. His family played an important role in the development of the paper and pulp industry in northern New York. His great grandfather, Illustrious Remington, was one of the pioneer newspaper manufacturers in the area.

Remington also was active in the community as a member of the Jefferson County Golf Club and Black River Valley Club.

When he decided to pursue an Army commission, it was endorsed by a number of prominent businessmen and officials, including the secretary of state. In 1916, Remington completed Citizens Military Training Camp at Plattsburgh Barracks.

Upon graduation from the first Officers’ Training Camp at Madison Barracks in 1917, Remington earned the rank of captain. He was later transferred to 1st Infantry Headquarters in Binghamton.

Remington completed the Light Artillery (Horsed) War Course at the School of Fire for Field Artillery, Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in May of 1918. A month later, he deployed to France with the 350th Field Artillery, 92nd Division, as part of the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I.

He kept in touch with his wife while on deployment – his letters providing some insight into what he was seeing and hearing in battle:

“We are now very near the front and could hear the guns this morning. I am glad to go to the front, yet I feel that a little will be enough. It will show whether we have learned anything about the game or not.”

Two days later, he wrote again.

“Today part of our battery goes into position. Saw German airplanes under fire by our men and heard considerable shooting. Some of the villages near our position have been pretty well shot up while others are almost untouched. Women and children are living unbelievably close.”

Remington saw many heavy engagements during the war, and he received a battlefield promotion to major just before the armistice was signed.

Following his tour of duty, Remington separated from active-duty service as a major in April 1919. He entered the U.S. Army Reserves and commanded two battalions, the 481st and 367th Field Artillery. While serving in the Reserves, Remington continued his employment with Kamargo Supply Company as secretary.

In the 1920s, there was discussion in Albany about transforming the LeRay Mansion district into a state park. However, with the estate adjoining the Pine Plains training encampment, National Guard leaders considered acquiring the 2,000 acres of land.

The property was in foreclosure when Remington, who resided on Paddock Street in Watertown with his wife and two sons, purchased LeRay Mansion in November of 1936. He commissioned a well-known architect in the area, Albert Skinner, to restore the mansion to its original grandeur. The Victorian-era plumbing was updated, wood flooring in the basement was replaced, and electricity was installed.

Remington’s wife, Margaret, went to the B. Altman and Company department store in New York City with the floor plans of the mansion to get assistance with selecting new furnishings. The Remingtons invested roughly $30,000 in renovating the property.

This detail was discovered by the Fort Drum Cultural Resources staff in recent years, after Margot Remington, granddaughter of Harold Remington, allowed them to borrow her collection of photos, letters, newspaper clippings and other historic documents.

“You can just imagine this lovely lady going to this luxury department store in the city – and money is not an object – and she’s telling them where to put this couch or that table,” said Dr. Laurie Rush, Fort Drum Cultural Resources Program manager. “According to Margot, her grandmother gave names to every room – the library, the parlors and such.”

Rush said that Margaret Remington was enamored with the mansion well before they purchased it.

“Mrs. Remington already had a whole collection of newspaper clippings about the house, and she was so interested in its history before they even bought it,” she said. “She cut out a whole history of the mansion out of newspaper articles from 1910.”

Without the Remingtons’ restoration of the mansion, during the Great Depression no less, this landmark would almost certainly have deteriorated beyond repair if left unattended another decade.

The Remington family resided in LeRay Mansion for five years until the U.S. government invoked eminent domain and purchased 75,000 acres of land for the Pine Camp expansion. The War Department had determined that the Pine Camp reservation would not be adequate for the training of an armored division scheduled to be stationed there.

Five entire villages were eliminated (Sterlingville, Woods Mill, Lewisburg, LeRaysville and Alpina), while others were reduced in size; 525 families were displaced and more than 360 farms were lost.

The Remingtons also were ordered to vacate their property, but from January until October of 1941, they campaigned to keep their home. They presented their plea in letters sent to all levels of authority – from the commanding officer of Pine Camp and senior Army officials to all local, state and national branches of government.

According to his correspondence with one member of the U.S. House of Representatives, Remington said that he understood the original plan was to acquire “poor land to the north and northeast” of the training camp. But the proposal that the War Department made public would take “the best land, some 75,000 acres to the west running from Calcium to Antwerp.”

Part of the reason they took matters into their own hands, as explained in one correspondence, was that much of negotiations for land acquisition involved the Army and county businessmen. The land owners were not given a forum to express their views.

One general officer wrote a letter of record on behalf of the Remingtons:

“I was in command of Madison Barracks and Pine Camp in 1924 and 1925 and know the situation pretty well there. Mr. Remington owns the historical old LeRay Mansion which was in ruins in 1925 but which he has rehabilitated as a private residence. While the land about the Mansion is not particularly rich, it is built up and cultivated with a considerable number of people living on it, and I think it would be a shame to dispossess them unless necessary.”

The commanding officer offered an alternate area of land to consider, as had the Remingtons. Ultimately, the War Department deemed the land essential for field training and maneuvers, and a letter from the Army deputy chief of staff explained that “exempting the Remington property would seriously interfere with the use of the entire tract for military purposes.”

In a letter to the 2nd Corps Area commander, in Governors Island, Remington proposed that a representative of the armored division investigate the central portion of the LeRay Mansion property. He argued that it was not as useful as they believed, and that it would be easier to arrange entrances to the maneuver areas through the north and south extremities of the property – land he was willing to sacrifice to save the historic landmark.

“The property lies so close to the barracks area and its character is such that it will have to be by-passed no matter whether it belongs to the Government or still remains in my possession,” he wrote.

According to a local news report, they were offered $50,000 for the property, which included the mansion, farmhouse, barn and tenant house situated on roughly 1,700 acres of land.

Remington had the property appraised as being worth three times that amount, and he filed a civil action in U.S. District Court for the Northern District of New York. Court documents indicate the actual amount offered to Remington was $57,500, which he stated was “grossly inadequate.”

It was a losing battle for the retired Army colonel, and the Remingtons eventually purchased and moved to an estate in Cape Vincent. However, LeRay Mansion was never far from their thoughts.

“The Remington family was heartbroken when they lost their home, after fighting the Army in court over it,” Rush said. “After World War II, Mrs. Remington wrote a letter to President Eisenhower requesting that the house, at the very least, be given back to the community.”

In April 1955, Margaret Remington corresponded with the New York District Corps of Engineers with a request for information on how to obtain custody of the mansion. She contacted members of Congress for support. In her letter to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, she stated that the mansion, whose cultural influence has left its mark on northern New York, has been left mostly vacant since the deactivation of Camp Drum.

As chairman of the LeRay Mansion Committee, she wrote: “We of LeRay de Chaumont Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, apprehensive of what may happen, would like to be given the authority to take charge of this federally owned building and to open it to the public as a historical monument in Jefferson County.”

LeRay Mansion was listed in the National Register of Historic Place in 1974. Over the years, the mansion has served as living quarters for senior military leaders and as a bed-and-breakfast for visiting dignitaries.

Prior to the Remington family owning the property, their pond was known as St. James Lake – named after its original owner, James LeRay. Presumably, it was renamed as Remington’s Pond under the new ownership and later became known as Remington Pond.

In the 1980s, the Directorate of Family and Morale, Welfare and Recreation assumed responsibility of the Remington Pond Recreation Area (which included Remington Park and Remington Beach). Since 2018, the LeRay Mansion district has been managed by the Directorate of Public Work’s Cultural Resources Branch.

To learn more about the Remingtons at LeRay Mansion, visit www.leraymansion.com and follow www.facebook.com/FortDrumCulturalResources.

Social Sharing