This is the first of a series of six articles looking at the 160-year history of Rock Island Arsenal, Illinois. The first article will look at the arsenal from its establishment as a military fort to the end of the Civil War. The second article will focus on the arsenal’s role in supplying the Army during the Spanish-American War and leading up to World War I. The third article will examine the arsenal’s history from 1917 until 1942. The fourth article will look at the arsenal during World War II and the Korean War. The fifth will look at the arsenal from the mid-1950s to the end of the Cold War. The last article will focus on the Gulf War to the present.

ROCK ISLAND ARSENAL, Il. – On May 10, 1816, the U.S. Army established a fort on an island in the middle of the Mississippi River known as Rock Island. The new installation, named Fort Armstrong after John Armstrong, the Secretary of War under then-President James Madison, was built as part of a chain of western frontier defense posts that were established after the War of 1812.

In 1832, the fort became the logistics headquarters for the U.S. Army during the Black Hawk War. After the war ended, the fort fell in to general disuse, and was largely abandoned by the Army by 1836. However, it was still retained as a federal reserve.

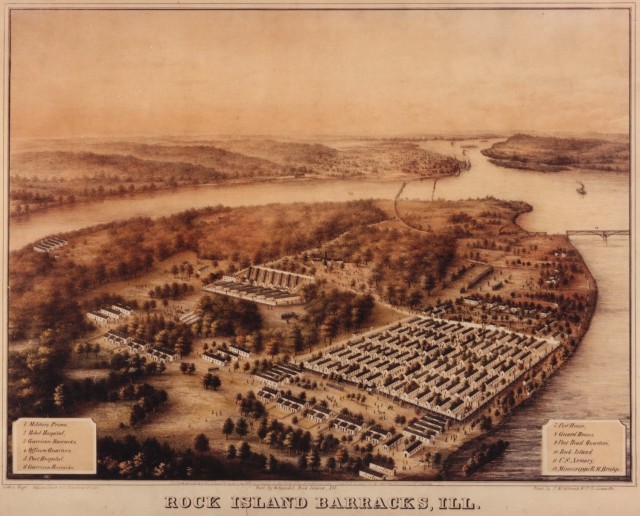

On July 11, 1862, the abandoned fort and the island as a whole, was re-designated as Rock Island Arsenal by an Act of Congress which established an arsenal and national armory for the U.S. On Sept. 1, 1863, ground was broken for the first building.

Rock Island was chosen as the site of the national arsenal due to its strategic location in the Mississippi River and readily available source of natural river power. Brig. Gen. George D. Ramsey, chief of Ordnance, explained this in a letter to Edwin Stanton, the U.S. Secretary of War, in 1864.

“In a military point of view it is perfectly secure from an enemy advancing either by the lakes or the river. From it supplies can be transported in any direction and at any season of the year. It is in the midst of a country teeming with coal and wood, and especially adapted to agriculture. The site is elevated far above river floods, the climate and situation are healthy; and while the Island is sufficiently located to secure it from sudden attacks, it is near enough to the cities of Rock Island, Davenport and Moline to afford ample accommodations for all the necessary employees.”

From 1863 to 1865, the arsenal played two significant but vastly different roles in the Civil War. The first, as mandated by Congress, was to serve as a shipping and storage supply center for Union troops; the second was as a prisoner of war camp for Confederate soldiers.

While Rock Island was never intended to be a POW camp, it was an ideal location. The island was far away from the fighting, owned by the government, sparsely occupied, and secure.

In August 1863, Captain Charles A. Reynolds, under the orders of Brig. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs, Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army, began to survey and construct a camp to accommodate 10,080 POWs.

However, Union victories during the summer and fall of 1863, as well as overcrowding at existing POW camps, forced the Rock Island Prison Barracks to be occupied before the camp was ready to accommodate prisoners.

The first 468 prisoners arrived in December 1863. They had been captured at the battles of Lookout Mountain in Tennessee the month prior. By the end of the month, there were nearly 5,600 prisoners held at Rock Island.

The rapid influx of prisoners, many of whom were sick with various diseases, into an unfinished camp, meant that conditions were not initially great. According to a 2014 article which ran in the Des Moines Register, the camp was, “primitive at best, and many of the prisoners arrived in poor physical condition.”

Compounding matters for the prison administration, western Illinois was coping with one of the worst winters on record. The freezing temperatures, and lack of supplies, meant that the camp quickly ran out of blankets and warm clothing, as well as fuel to heat the stoves in the barracks.

Over the next few months, however, the prisoners’ conditions generally improved as they received medical attention, food and proper clothing.

The prisoners were allowed a great deal of freedom within the camp. They were permitted to read newspapers and books, exchange letters with their families and friends back home, and receive care packages. They also received the same rations as the Union soldiers guarding them. The rations the prisoners received were so good that many of them began gaining weight and had to be put on a diet of 3/4ths rations to help control weight gain.

Many prisoners also made trinkets to sell to the local community, or made money helping to build the camp reservoir and sewer system. The prisoners were paid with scrip that they could use to buy “luxury” items such as cards, tobacco and other amusements from local sutlers who would visit the camp.

Disease was a constant, and frequently a losing battle for both the prisoners and guards. By early 1864, nearly 700 prisoners and guards had died due to an outbreak of smallpox. In response to the outbreak, the prison superintendent, Col. Adolphus Johnson, quarantined the sick prisoners and built a hospital on the grounds, as well as a pest house to quarantine the sickest prisoners. Due to these efforts, the smallpox epidemic was over within a few months.

Even though Johnson and his guards did their best to treat the prisoners humanely, Rock Island gained unfounded notoriety as a hellhole, thanks to the efforts of a local newspaper editor and author.

Johnson’s efforts to take care of his charges weren’t enough for J.B. Danforth Jr., the editor of the Rock Island Argus. According to the Des Moines Register article, Danforth published “undocumented stories about the ‘deliberate’ murder of the prisoners at the camp,” through starvation and disease. Danforth was against the war, and targeted the prison as the focus of his antiwar efforts.

Over the next year, Danforth would continue to publish articles about the camp; even going as far as implying that the superintendent and guards were war criminals.

After the war, as the myth of the “Lost Cause of the Confederacy” began to take hold in the South, rumors about horrific conditions at the Rock Island Barracks continued to spread as former Confederate prisoners at Rock Island began to tell stories about the camp. However, these stories must be taken with a grain of salt as the historical records do not support most of the claims.

The “Lost Cause of the Confederacy”, attempted to paint the cause of the war as heroic and as fought to protect their economy and their people against Northern aggression. It was further claimed that the Confederate states, which possessed greater morality and military skill then the North, only lost due to the Union having more industrial capacity. This movement has been overwhelmingly discredited by modern historians.

In 1936, Margret Mitchell reintroduced the idea of the alleged brutality at the prison barracks to a new generation of Americans. In her bestselling book, “Gone with the Wind,” she referred to the camp as the “Andersonville of the North” and repeated many of the rumors about the RIA prison that had been spread by those wishing to rewrite the Confederacy as a, “noble cause.”

Andersonville Prison was a Confederate POW camp that gained infamy for being the most notorious of any Civil War POW camp, due to the brutality of the guards, overcrowding, and a 27 % fatality rate due to disease, starvation and exposure.

In Mitchell’s book, Confederate soldier Ashley Wilkes is captured by the Union Army at the Battle of Gettysburg and sent to Rock Island as a prisoner of war. Mitchell wrote that Wilkes’ family, while relieved that he was alive, were horrified that he had been sent to Rock Island, as it was viewed by many Confederate citizens as hell on earth.

“At no place were the conditions worse than at Rock Island,” Mitchell wrote in her novel. “Food was scanty, one blanket did for three men, and the ravages of smallpox, pneumonia and typhoid gave the place the name of a pesthouse. Three-fourths of all the men sent there never came out alive.”

The historical records prove that Mitchell’s writings of the 75% death toll are not true. During its two years of operation, 12,192 Confederate prisoners of war were held on the island. Of those, 5,581 prisoners volunteered to join the Union as galvanized Yankees, and 1,964 died. A cemetery, which still exists today, was established for their burial on the grounds of the arsenal.

As the Civil War ended, a national cemetery was established on the arsenal. The first Soldiers interned here were Union soldiers that died while serving as guards. Since then, the cemetery has expanded to 66.8 acres and is the final resting place of Soldiers who served in every conflict since then.

After the camp was closed in July 1865, the barracks were torn down and the construction of an ordnance arsenal resumed. All that remains of the Prisoner of War camp on Rock Island Arsenal today is the Confederate cemetery and a historical plaque on the corner of Blunt Drive and East Street.

Information for this article was found at the Rock Island Arsenal archives.

Social Sharing