ABERDEEN PROVING GROUND, Md. – May is Lyme Disease Awareness Month, and the U.S. Army Public Health Center wants to remind everyone to protect themselves against Lyme and other tick-borne diseases. The APHC is constantly evaluating tick-borne threats to Army personnel through the surveillance of both human Lyme disease cases and the infected ticks themselves.

Diseases spread by arthropods such as ticks are known as vector-borne diseases; unlike infectious or contagious diseases such as COVID, vector-borne diseases cannot be transmitted from one person to another. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne disease in the U.S., with more than 300,000 new cases estimated to occur every year.

Lyme disease is caused by bacteria that are transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected blacklegged tick, commonly known as the deer tick. Because ticks are more active during warmer months, new Lyme disease cases in the U.S. are most commonly reported from April to September, peaking in June and July when extremely tiny, immature blacklegged ticks known as nymphs are active.

To transmit Lyme disease, an infected tick must be attached for approximately 36 to 72 hours so the bacteria in its saliva can be transferred. For this reason, prompt tick removal reduces your chance of getting sick. Unfortunately, most people are infected through the bites of nymphs, which are smaller than a sesame seed and thus difficult to see.

Typical symptoms of Lyme disease include fever, headache, fatigue and a characteristic “bull’s eye” skin rash, although the rash does not appear in all cases. If caught early, most cases of Lyme disease can be treated successfully with a few weeks of antibiotics.

“Unfortunately, in many cases you might not see the bull’s-eye rash, so Lyme disease can be very challenging to diagnose,” says Dr. Robyn Nadolny, the chief of the APHC Vector-Borne Disease Branch.

“If left untreated, Lyme disease can spread to your joints, heart and nervous system. In some cases Lyme disease can cause permanent health problems, like arthritis, heart conditions and cognitive impairment,” says Nadolny.

“Lyme disease is a serious health problem,” says Nadolny. “There are currently no vaccines for Lyme disease approved for human use on the market, so preventing tick bites is the best way to avoid Lyme and other tick-borne diseases.”

Nadolny runs the APHC’s MilTICK program, a free tick testing service for ticks removed from Department of Defense personnel and their dependents. Any tick found biting an eligible person can be submitted to MilTICK by individuals through a simple mail-in process, or by healthcare providers through tick kits at DOD healthcare facilities. The results are reported back and can help doctors decide whether or not to treat for Lyme or another tick-borne disease.

The APHC is also charged with tracking of human Lyme disease cases reported through the Disease Reporting System internet at military treatment facilities. Cases captured in the DRSi include active-duty Soldiers as well as other beneficiaries receiving care at Army MTFs.

“From the last five years of DRSi data we see similar patterns of Lyme disease cases as those captured in the civilian population by the CDC, such as higher numbers of cases in June and July, and more cases among men,” says Kiara Scatliffe-Carrion, a senior APHC epidemiologist.

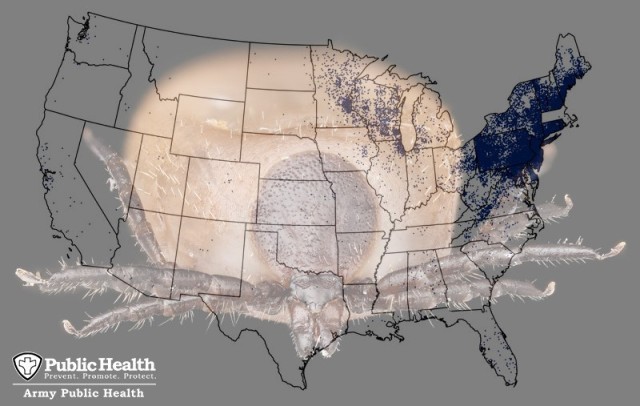

“We also found that many active-duty cases were reported by the U.S. Military Academy at West Point,” says Scatliffe-Carrion. “This corresponds to the CDC’s identification of the Northeast region of the U.S. being an especially high-risk area for Lyme disease.”

Scatliffe-Carrion explains that because of underreporting in DRSi, the data may underestimate the public health significance of Lyme disease among Soldiers.

Underreporting is common in systems like the DRSi since they require health care providers to submit disease case reports as a separate step following medical treatment. In addition, Lyme disease diagnosis can include specific laboratory tests. Providers may choose to treat for the disease based on symptoms and exposure to ticks but not report the case.

“Since DRSi data help the military target areas to mitigate disease risk, medical providers are encouraged to be familiar with the clinical presentations of Lyme disease and DRSi reporting guidelines,” says Scatliffe-Carrion.

While enhanced Lyme disease reporting in the DRSi is warranted, Nadolny emphasizes the importance of practicing prevention and participating in exposure surveillance programs like MilTICK.

“Data from ticks submitted to MilTICK help us assess areas where tick-borne diseases are emerging as well as changing risks to DOD personnel. So not only do you get peace of mind from knowing if your tick was infected, you can also feel good about contributing to citizen science.”

Steps to prevent Lyme disease include avoiding exposure to ticks, using proper tick repellent when in high-risk areas, conducting tick checks after spending time outside, and removing ticks promptly.

Before you go outdoors – be aware of your risks.

Spending time outside hiking, camping or hunting could bring you in close contact with ticks. Engaging in activities around your home, such as walking your dog, gardening and yard work can also expose you to ticks.

- Find out if you are in a high-risk area and need to take extra precautions; New

England, the mid-Atlantic and the Midwest are all very high-risk areas for Lyme

disease. - Walk in the center of trails and avoid tick habitat, such as wooded or brushy areas with high grass or leaf litter.

- Make your yard less attractive to ticks by mowing your lawn, removing habitat for mice and other tick hosts and creating “tick-free” barriers between your yard and wooded areas.

- Wear approved repellents, such as those containing DEET, on exposed skin, and follow the DOD Insect Repellent System.

- Treat clothing and gear (never skin!) with products containing 0.5% permethrin.

- Consult with your veterinarian for the most appropriate tick prevention for your pet.

When you come indoors – check for ticks.

- Check your clothing, or throw your clothes in the dryer on high heat for 10 minutes. Additional time may be needed for damp clothes.

- Carefully check pets, coats and packs for ticks that can attach to a person later.

- Shower within 2 hours of coming indoors; doing so will help remove any crawling ticks, and you can also check for attached ticks.

- Conduct a full-body tick check after being in potential tick areas, including your own back yard. Use a mirror to view all parts of your body, or use the buddy system.

- Don’t forget to check your kids for ticks! Ticks like to hide where fabric or skin folds, and they can also bite the scalp under the hair.

If you find a tick on you, don’t panic.

Remove it with tweezers immediately. It is possible the tick was not infected, and if you found it before it was attached for several hours, your risks are low. If you are concerned about the possibility of tick-borne disease, save the tick and submit it to MilTICK for testing, or contact your doctor.

—END—

The U.S. Army Public Health Center focuses on promoting healthy people, communities, animals, and workplaces through the prevention of disease, injury, and disability of Soldiers, retirees, family members, veterans, Army civilian employees, and animals through population-based monitoring, investigations, and technical consultations.

NOTE: The mention of any non-federal entity and/or its products is for informational purposes only, and not to be construed or interpreted, in any manner, as federal endorsement of that non-federal entity or its products

Social Sharing