Since the Civil War, the United States had not fought an enemy on American soil nor had an enemy of the U.S. captured or held U.S. soil. This changed in 1941, when the Empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, bringing the U.S. fully into World War II. Then again, in early June 1942, the Empire of Japan attacked and took the islands of Attu and Kiska in the Aleutian Island chain of Alaska. Now, not only was the U.S. at war with the Empire of Japan, but the Empire had struck first, captured U.S. soil, taken U.S. prisoners, and now occupied U.S. land.

Strategic occupation

Located on the far reaches of the Aleutian Island chain, the Japanese presence posed by their occupation of Attu and Kiska might have seemed a miscalculation on the surface, when in reality it represented a threat of strategic significance. Historians have debated the reasons why the Imperial Army invaded the islands (and attacked the base at Dutch Harbor). Some say it was to divert American forces away from Midway, while others postulate it was to develop a foothold for a full invasion of Alaska, and then the rest of the country. Still, others believe Japan intended to use it as a position to block Russia from aiding the U.S. should Russia enter the war against the Empire.

The islands of Attu and Kiska were the primary focuses of the Imperial invasion. Once successfully occupied, the Imperial Army constructed airfields and prepared for the inevitable counter-attack by the Americans. Attu was sparsely populated with less than 30 inhabitants, all of whom were removed by force and interned in Japan (most died during their internment. Beyond the civilian population, Attu had no military forces stationed there, while Kiska had a small 10-man weather station yet no permanent civilian population. However, it is Attu that is known for where America’s first foreign enemy would occupy and fight on U.S. soil in nearly 60 years.

7ID prepares to reoccupy Attu

Attu possessed no real physical threat to the mainland U.S. But due to its geographical proximity to the mainland, the strategic vulnerability posed by its occupation meant that Attu and Kiska had to be retaken. This is where the 7th Infantry Division entered the picture.

Around the time of the Japanese invasion, 7ID was training at Fort Ord, California and was selected to be part of plan to expel the Imperial forces due to their training readiness and availability. This was when the Bayonet Division received a new training task – rehearsing amphibious landings – which occurred under the direction of U.S. Marine Corps Maj. Gen. Holland and U.S. Army Maj. Gen. Albert Brown (7ID’s Commander). The landings provided the necessary knowledge of how to conduct amphibious landings and aid in securing Attu. Yet, the terrain and weather of Attu proved as much of an obstacle as the enemy.

Weather, the other opponent

Attu had an interesting quirk about its weather. Due to warm ocean currents, there was a consistent fog that almost always veiled the island and prevented its tundra form fully freezing. The land could barely support the weight of a soldier, much less vehicles or artillery guns, forcing the 7ID to have fight the island's terrain itself as well as the Imperial forces there. Generally speaking, this meant a degraded conditions for the Division’s movement across the island.

Unexpected enemy numbers

The day finally came when the Bayonet Division completed training at Fort Ord. Yet, before they departed San Francisco, the enemy situation on Attu changed. On April 24, 1943 it was reported that instead of the estimated 500 soldiers occupying the island, intelligence suddenly projected Imperial forces to have grown to around 2,400. This meant that shortly before their departure, General Brown, would gain additional units swelling his total number of soldiers to approximately 11,000, and bringing the total number of Americans involved at Attu to 15,000 (including Navy and Coast Guard personnel).

Once in range of Attu, the weather predictably demonstrated why it was going to be a difficult place to fight. Due to mostly fog and wind, the weather forced the first of several delays, pushing the Attu D-Day landing back four days from its original date of May 4, 1943. Then another day. And another. Until finally, Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid realized that the weather was not going to clear. He then set the last and final invasion date for May 11, 1943.

D-Day Attu

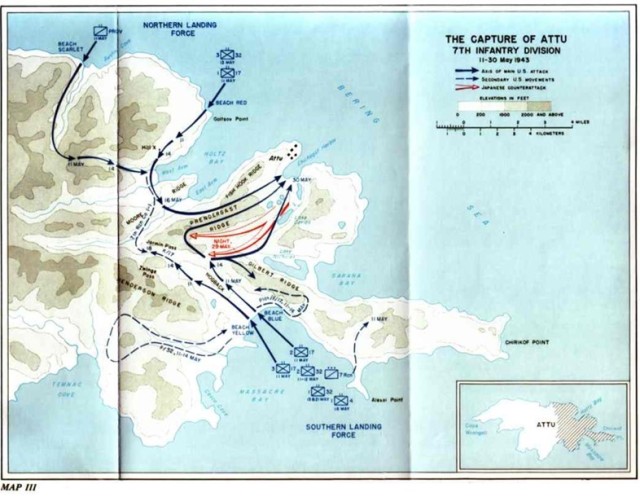

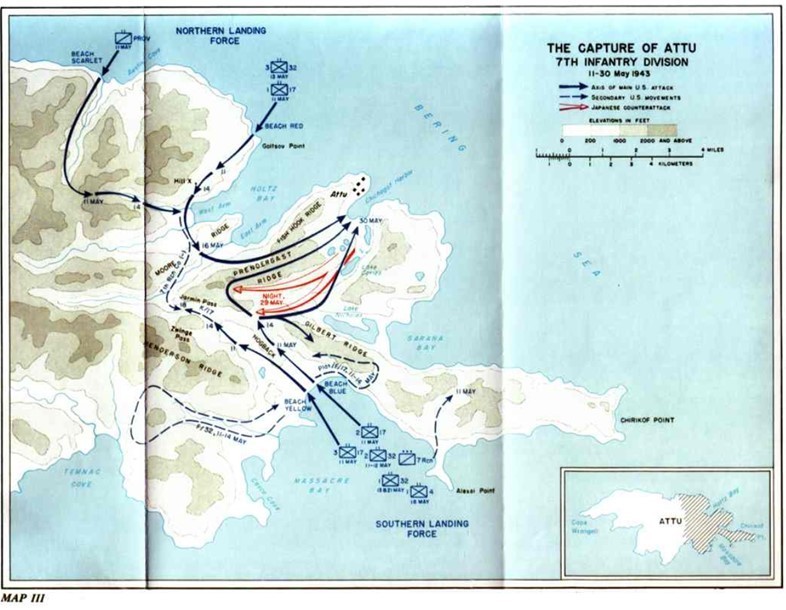

The Attu invasion began with the 7th Scout Company paddling ashore in the predawn darkness to Beach Scarlet, as part of the Provisional Battalion (of the Northern Landing Force). Shortly after the 7th Scout Company made it ashore, dense fog encircled the Attu making the rest of the landings difficult. Despite the fog, the first wave had completely landed by 8 a.m. Unfortunately, the ability to land additional troops became so difficult, Maj. Gen. Brown refused to send more troops until he was sure that the landing craft could return to the ships. Around 12:30 p.m. the general received word from Lt. Col. Albert E. Hartl that Beach Red (in Holtz Bay) could support the remainder of the landings. About the same time as he received Lt. Col. Hartl’s message, Maj. Gen. Brown also received word that the weather would improve in the afternoon. He then authorized the deployment of the main landing element to begin at 3:30 p.m. at beaches Yellow and Blue in Massacre Bay.

Once the landings began in force, they became routine. Intelligence reports indicated Imperial forces were in semi-fortified positions, which ran contrary to the initial belief that Imperial forces would meet any invasion force on the beach. Even the Empire failed to realize that Attu would be grounds for the first battle site for the Aleutians until 2 a.m. on May 11, 1943 when planes from the carrier Nassau conducted a bombing/strafing run over Chichogof Harbor, dropping leaflets demanding their surrender and announcing the oncoming assault. The invasion was a success, due in large part to preparations at Fort Ord and heavy fog that obscured both American ships and troops. Additionally, the chosen site for the largest landing force (Massacre Bay) was protected from the Imperial positions by a ridge line.

Three weeks of battle

The Battle of Attu began on May 11 and ended on May 30, and contained itself to the eastern side of the island. Progress was initially slow due to weather, terrain, and poorly equipped ground forces. The 7ID, fresh from training in California, was still equipped for fighting in a warmer climate and was never issued cold weather gear in bulk in order to obscure their cold weather mission public observation. In the end, the invasion involved over 15,000 Americans against roughly 2,400 Imperial soldiers. A total of 549 Americans gave their lives for Attu, with another 1,148 wounded, and 2,100 evacuated for disease and non-battle injuries (mostly due to the extreme cold). One soldier was recognized in particular for his actions. Pvt. Joe P. Martinez was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions on May 26, 1943, when he led an American charge that captured over 150 feet of land and inspired his fellow Bayonet soldiers to continue fighting, eventually leading to the capture of the Holtz-Chichogof Pass. This enabled 7ID a greater freedom of movement and would become a decisive point that led to the end of the battle. The Battle for Attu, however, ranks as one of the costliest assaults in the entire Pacific Theater. In terms of Imperial forces destroyed, the cost of re-taking Attu is second only to Iwo Jima. For every 100 of enemy forces on the island, about seventy-one Americans were killed or wounded.

Even though the cost was high, Attu was once again in American control.

____

Evan Muxen is the Historian for the 446th Airlift Wing, ARFC, located at Joint Base Lewis-McChord. He previously served as the Command Historian for the 18th Wing at Kadena Airbase in Okinawa, Japan, the U.S. Air Force's largest combat wing.

Social Sharing