FORT LEE, Va. – The road that brought 1st Sgt. Eric Latson to Fort Lee started out as an escape route and meandered its way through the elite realm of All Army Sports and the demanding dusk-to-dawn world of a 92G culinary specialist.

Looking back on the journey, the 39-year-old enlisted leader of Charlie Company, 262nd Quartermaster Battalion, realizes how it imbued him with a prizefighter’s mentality – the unshakeable belief that teambuilding is key to winning and success is unachievable without hard work and unwavering determination.

Latson’s story begins in Liberty City, a six-square-mile section of Miami widely considered as the “bad part of town.” In the late 1980s and ‘90s, it often grabbed the national spotlight because of drug-related crime. Today, it lists an unemployment rate of 13.4 percent and more than half of its grade-schoolers drop out before completing their senior year, according to the Miami Children’s Initiative website.

“In Liberty City, definitely a well-known area of Miami, you have limited options – one being death; one being drugs; one joining a gang; and one finding a way out,” Latson observed.

Four siblings, born to a mother of Bahamian descent, influenced his choice to overcome the conditions and influences that doomed others in the community. Latson’s two eldest brothers, one sentenced to prison and the other in and out of juvenile detention, were living evidence of the ruin inflicted by the streets. The younger two represented the prospect of better tomorrows.

“I could have easily followed the older two – do the wrong thing and get locked up,” Latson offered hypothetically, “or I could be an example for the younger two. Through positive actions, I would basically be saying, ‘Although this is the example being set for me, I don’t have to choose that route.’”

While he made every effort to do the right thing, there was no overcoming Liberty City’s whirlwind of generational poverty. Latson soon recognized that his younger brothers were heading down those well-worn paths leading to criminal behavior. The fortunate redemption for him was the decision during his teenage years to move in with his grandmother, Edna Latson, a disciplinarian and full-of-faith Christian who insisted upon a structured environment within her walls.

“She was an island girl who could cook the house down, but you couldn’t fix your own plate when she had ox tails,” Latson recalled with a bit of a laugh and an explanation that his grandmother was territorial in the kitchen. “Above all, though, she wanted to see everyone do well. That’s what really counted.”

Karen, Latson’s cousin, and her siblings were living with Edna prior to him moving in. She was about the same age as Eric’s second oldest brother and was as focused as they come. Heavily involved in school academics, JROTC and the church choir, Karen possessed enough ambition to leave vapor trails for anyone willing to take a whiff, including Eric.

“My cousin was definitely the foundation for my aspirations at the time,” Latson said. “She’d be like, ‘Look, get your butt in school, do the right thing and you’ll see people do good for you.’”

It opened his eyes and mind to new opportunities in addition to those that had always been available. He became member of the Miami Northwestern Senior High School track and field team and joined the math club. He earned a spot on the tennis team, and in 2000, became only the second African-American athlete from his school to play in the state tournament.

“With everything I was involved in, I learned that I have a very aggressive nature,” Latson observed. “I’m very competitive. I’m not going to boast or brag about doing this or that, but when it’s time to shine, the first thing that comes into my head is, ‘I’m not about to lose.’”

Latson knew Liberty City would never be a bastion of opportunity, so he had already worked out plans for departure, mostly influenced by his time as a high school JROTC cadet.

“I joined the military to better myself in a way the streets of Miami was not able to afford me,” he said of the decision. “I saw death, drugs, violence and poverty at a young age, and knew I had to surround myself with ‘better’ in order to get better.”

Choosing to train as a culinary specialist was a natural choice because, growing up in his family, “one thing not crippling you was the ability to cook.” Thus, when 92-golf was offered, he “jumped at the opportunity.”

Latson went on to work at dining facilities in Vicenza, Italy – his first duty assignment – and other military bases in the states as well as Southwest Asia while deployed. While serving at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Wash., he successfully applied for the All Army Volleyball Trial Camp in 2009. He had only dabbled in the sport, but felt confident he could make a good showing based on successes as an intramural and club ball player.

“I got to Fort Bragg (N.C., site of the trial camp) and sat on the bench the entire season,” he scoffed dismissively.

The reputation he grew at JBLM was not commensurate with the skills needed to compete at All Army level. He also suspected that he made the team simply because of mass absenteeism as most of the veteran players deployed that year.

“It was nothing to brag about,” Latson huffed. “In my head, I got cut that year.”

At the same time, though, the bench-warming affair served as motivation. Latson returned to JBLM vowing to never again sit on the sidelines, relentlessly working on his physical conditioning and all aspects of his game through a rigorous program of self-improvement.

“I lost my mind,” he said with a bit of hyperbole. “I went volleyball full-throttle, playing for different clubs and teams in the Seattle area.”

Latson was a different player upon receiving a second invite to All Army in 2010. Mentally, he was more-focused. On the court, his skills were two notches better. Physically, he was quicker, stronger and more explosive. Additionally, the stigma of making a weak team was non-existent since the camp was bulging with the Army’s top talent.

“I ended up starting … as the middle (player),” Latson said. “That year, we finished second in the (Armed Forces volleyball) tournament.”

Yet, that was still not good enough for ultra-competitor. He set his sights on making the All-Armed Forces Team that represents the country in global sporting events such as the International Military Sports Council (CISM) tournament.

“I went back home and honed my game even more,” he said of preparations for 2011, the year the All Army team went on a rampage, toppling the other services and claiming the Armed Forces title. “We had so much talent, the coaches and administrators literally wanted to take the entire Army squad and make them the Armed Forces team.”

Out of fairness, that did not happen, but Latson was one of those chosen to represent the Army. As such, he was able to compete in the World Military Games in Brazil that was a warmup for the 2012 Summer Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro.

“It was an all-expense paid trip to represent the U.S. in volleyball,” said Latson, incredulously. “I was absolutely living a dream.”

Latson went on to make the All Army Volleyball Team in 2012, 2013 and 2014 as well. In addition to his usual starting position, he served as team captain.

“After four years playing at that level, the question became, ‘What’s next?’” he said. “I had pretty much done everything including failing on a team, playing on a team, making the Armed Forces team, winning the tournament four years in a row, making the CISM team and the World Military Games team. We played at nationals; we played overseas … I was at the point – not that the fire died – in which I kind of felt like, ‘OK, what can I give back to the program that I couldn’t give as a player?’”

The choice became obvious. In 2015, Latson applied for and got accepted to serve as the All Army head coach.

“The good thing was everyone on the All Army staff knew who I was,” he said. “They knew what I brought to the program and team. Regardless of what was on my application, they knew what they were getting from me.”

Anthony Poore met Latson in 2011 while holding the general manager position with the All Army Sports Program at Joint Base Fort Sam Houston-San Antonio, Texas. It was not long before he recognized the skillset Latson bought to the table.

“He just has character,” said Poore, now the Clark Fitness Center manager at Fort Lee. “He is just a positive person. Also, he is a leader.”

Such a leader that he did not strong-arm program participants merely because he was in charge. Rather, Latson remembered his own experiences and operated from that perspective.

“I just thought about things as a player,” he shared. “What was good? What was bad? What were the good and bad things about me as a coach? I tried to do things that were completely different. … I tried to make it as fair as possible. I sent emails letting (qualifiers) know what my expectations were, and if they didn’t bring it, they were going back home in the first day or two.”

Latson’s coaching debut was not stellar. His team finished second at the Armed Forces tourney, although three players snagged an Armed Forces birth. It sufficed for the time being, Latson supposed.

“It was good enough for a first (coaching) experience,” he said. “I don’t think it was good enough for the competitive side of me.”

As Latson noted earlier, he is not one to gloat about accomplishments – how he took up volleyball as an adult and worked his tail off to improve and climb to the highest levels of the sport that many work at mastering over a lifetime. He seemed to take that part as a given. Surviving Liberty City had steeled him to be successful at anything, at any level.

“To much is given, much is required,” Latson said philosophically. “You can’t sit here and say, ‘I want to play at the top level’ but you are lazy. You can’t say, ‘I want to play at the top level’ and eat like crap. You can’t say, ‘I want to play at the top level,’ and don’t train to get there, right?’

“My mindset, especially coming from where I did, is to take care of business no matter what. I tell my Soldiers this all the time, ‘There is no plan B. Stick with plan A.’ Don’t let failure be an option.”

Conceptually, it is the near equivalent to “do or die.” If one’s will and determination is easily disrupted at the first sign of difficulty, then strengthening one’s resiliency is likely the first order of business

“If you have a mindset that can easily be broken, that’s the first thing you need to work on,” Latson said. “You need to ensure you are sure of yourself.”

Doing the work required for success also is at the heart of his approach to achieving any goal.

“If you are interested in something, do your homework,” Latson said. “I knew I wasn’t the tallest or most-experienced middle player trying out. I just knew that I was very versatile, and others were going to get tired before I did. I knew my training; what I put in it to make sure I had endurance. I was in the gym all the time doing my homework … I knew what it took to separate myself from the rest.”

He has done the same throughout his military career, becoming airborne qualified early in his enlistment and seeking out jobs that have moved him beyond kitchen duties at Warrior Restaurants. “Doing the homework” is the reason he is now serving as a company first sergeant.

“I want to challenge myself and work assignments that are outside of my military occupational specialty,” he said. “I feel like I have more to offer than just being identified as a 92G or ‘Cook.’ Culinary specialists and sustainers are some of the most well rounded Soldiers in today’s military. We are capable of doing it all.”

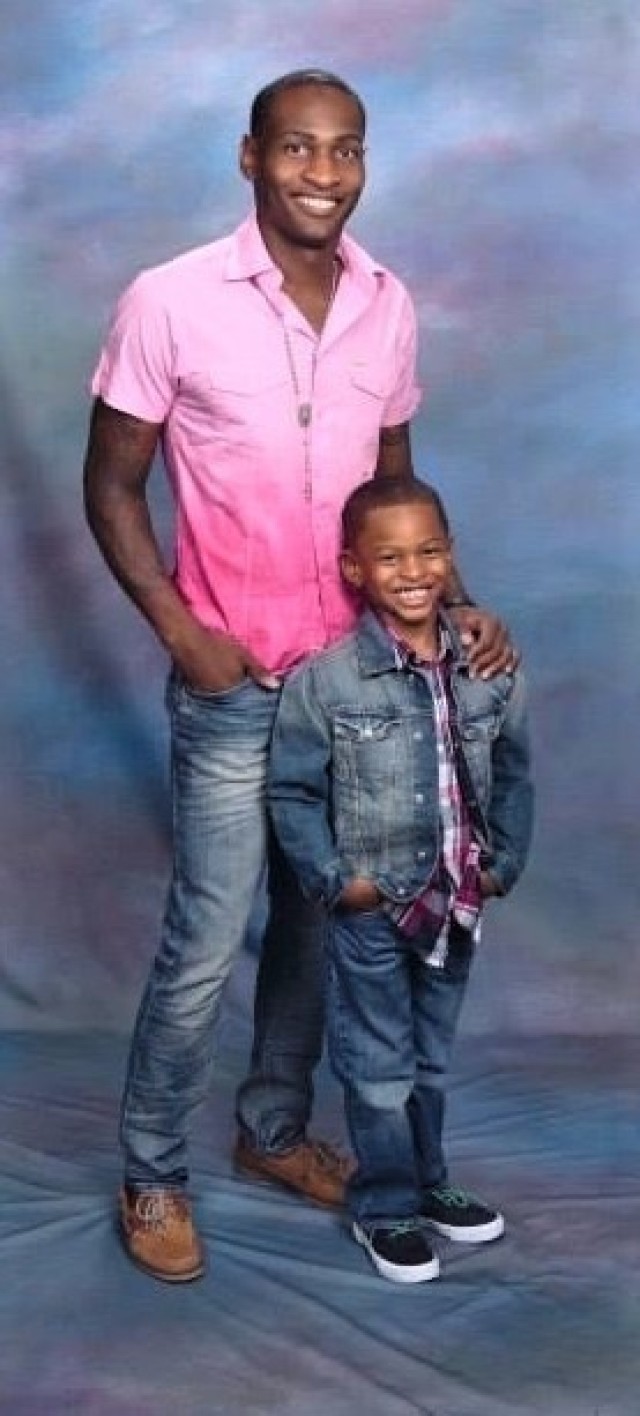

The truth of that statement carries over to his home life. Latson has been a single parent for more than 11 years. His 13-year-old son Christian is two inches taller and is a capable athlete.

Latson said he is very much aware that his successes as a Soldier, volleyball player and parent were made possible by subscribing to an uncompromising doggedness and taking advantage of every open window and crack of the door. The blessings have flowed as a result, he said.

“Opportunities aren’t given to everybody,” he said, with an immediate correction. “Let me rephrase that. Opportunities are given to everyone but not everybody seizes and capitalizes on them. I could have been this hoodlum that didn’t even look at tennis or track, but that opportunity presented itself to me, and I capitalized on that and was not afraid to do so.”

Latson’s youngest siblings, Errol and Gregory, were not so opportunistic. Two decades ago, their big brother proposed the idea of moving them out of Liberty City and joining him at his first duty station with the 173rd Airborne Brigade at Vicenza. It would have shown them better tomorrows are indeed possible.

Both declined the offer. They had been infected by the disease of hopelessness or perhaps fooled by the illusion street life could fulfill desires better and faster than anyone or anything else, said Latson. They were wrong.

“My next younger brother got killed in 2019 and the one under him is in prison right now,” Latson said. “I just don’t understand it. Five boys grow up in the same house but walk different paths. … All of them wanted the street life … I wanted to get away. All of this stuff I’d seen in magazines and on TV, I wanted to see it in real life, too. The lightbulb went off early in my head – there is more to life than Liberty City. Why couldn’t they see it?”

Gregory’s death, especially, moved Latson to a big-brother state of guilt. He went through iterations of asking whether there was any more he could have done to save his life.

“I can’t really say I blame myself, but here’s my doubt: Did I leave (Liberty City) too early?” he said in retrospect. “You know, when I graduated (from high school), was I supposed to stay? When I sent the plane tickets, did I push hard enough to make them get on the plane?”

The struggle with those thoughts brings urgency to what he feels is among his most important responsibilities as a senior NCO and company leader. It is helping junior Soldiers see the world of possibilities that military service affords them.

“I try to instill in Soldiers that not having or giving up on goals and dreams is not an option,” Latson emphasized. “I use my teamwork mentality from the volleyball years to build a cohesive unit/organization no matter where the Army sends me.

“I also use experiences and life in Liberty City to help me relate to the different walks of life that come through Charlie Company day in and day out.”

Moreover, to help him rise to the challenge and charge of his life – to help as many Soldiers as possible recognize that the Army is a bastion of opportunity and with a bit of hard work and dedication, better tomorrows are indeed possible.

Social Sharing