FORT DRUM, N.Y. (April 21, 2022) -- For most Fort Drum Soldiers and family members, it is simply known as Clark Hall – the place to go for in-processing, out-processing and everything in between.

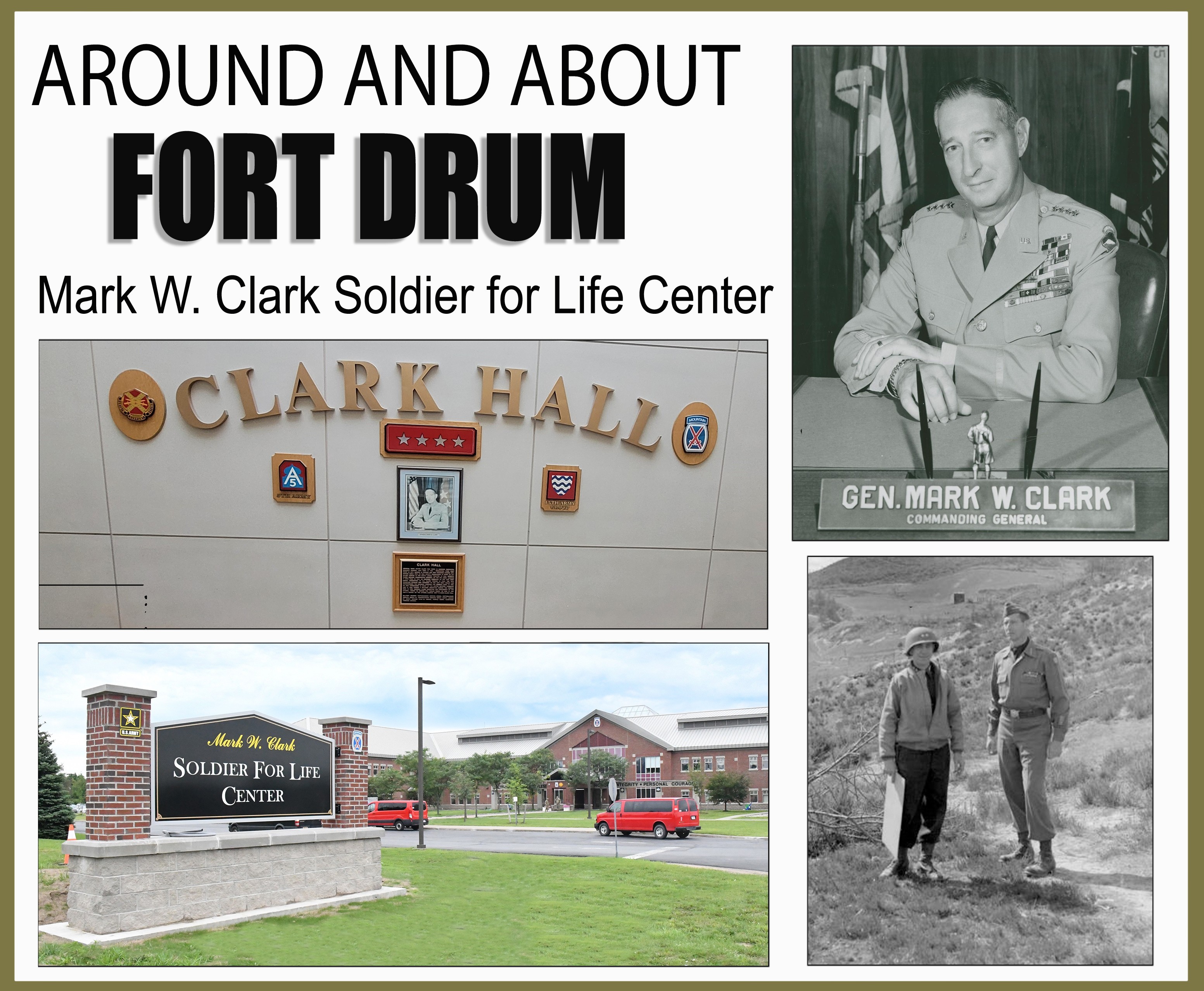

But in full, it is the Mark W. Clark Soldier for Life Center, named after a World War II commander who, some historians would say, ranks alongside Gens. Dwight Eisenhower, George Patton and Omar Bradley.

Mark W. Clark was born in Madison Barracks, Sackets Harbor, on May 1, 1896, to Charles and Rebecca Clark. He spent most of his youth in the Chicago suburb of Highland Park as his father, a career infantry officer, was stationed at Fort Sheridan, Illinois.

At age 17, Clark entered the U.S. Military Academy in June 1913 and befriended an older cadet, Dwight Eisenhower, who was Clark’s company cadet sergeant. Clark earned the nickname “Contraband” for smuggling unauthorized snacks into the West Point barracks.

Two weeks after the U.S. entered World War I, Clark’s class graduated early and he was commissioned as an infantry officer on April 20, 1917. He was assigned to the 11th Infantry Regiment of the 5th Division, and served as a platoon leader and company commander.

While deployed in France, Clark was wounded from a German shell in the Vosges Mountain. After being hospitalized for several weeks, he was deemed unfit for infantry service and was assigned to the First Army Supply Section.

Among his follow-on assignments, Clark managed a small entertainment detachment that traveled frequently across the U.S. From 1921 to 1924, he was assigned to the Office of the Assistant Secretary of War in Washington, D.C., where Clark again traveled extensively while disposing of surplus property and supplies. Clark graduated from the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia, and then served three years at the Presidio of San Francisco with the 30th Infantry before attending the Army War College.

In July 1937, Clark reported to the 3rd Infantry Division at Fort Lewis, Washington, as the U.S. Army began preparations for war. As the assistant chief of staff (G-2 and G-3), Clark was in charge of intelligence and training, and he helped to oversee a large-scale test of landing forces against simulated enemy opposition.

Clark was reassigned to work in the General Headquarters of the Army (GHQ), the field headquarters tasked with organizing, equipping and training the Army for combat. He traveled with Gen. Lesley J. McNair, the GHQ chief of staff, to Pine Camp (now Fort Drum), where the First Army was conducting maneuvers with National Guard and Army Reserve units.

The GHQ evolved into the Army Ground Forces, and Clark became chief of staff as a newly promoted brigadier general. He was instrumental in planning of large-scale maneuvers in Louisiana to assess all of the logistical operations needed to maintain great numbers of troops in the field.

In the lead-up to the U.S. entering World War II, Clark served as commander of the Army II Corps in England until Eisenhower tapped him to be his deputy commander-in-chief for Operation Torch in August 1942.

Clark helped lay the groundwork for logistics of stationing thousands of troops in the British Isles and then had a major role in planning the invasion of North Africa. But he was ready for more. As he wrote in “Calculated Risk,” “… I had been in the entanglement of planning so long that I had ‘ants in my pants’ and wanted action.”

Clark didn’t have to ask for it, either. On the morning of Oct. 17, 1942, he received a call from Eisenhower to meet him immediately. The French commander in Algiers had requested a secret meeting with an American delegation to discuss plans for Allied operations in French North Africa. Clark believed this meeting could yield cooperation instead of resistance during the Allied invasion of North Africa, and he would lead this covert rendezvous.

The contingent traveled by train and plane to Gibraltar before embarking, under the cover of night, in a submarine to reach the Algerian coast. At 6 feet 2 inches, Clark was always in danger of being concussed in the cramped confines of the sub. He said that he had to “literally crawl on all fours” to get to the bathroom.

Upon reaching the coastline, they waited for a light signal from French officers before approaching the beach by small boats and then moved stealthily to a house where the meeting convened.

After a full day of negotiations, it became known to them that police were notified – possibly by servants – and Clark and his staff hid in the wine cellar while the house was searched. They managed to leave the house undetected, contacted the submarine and escaped.

Clark traveled back to Algiers the day after the Allied landings on Nov. 9, 1942, and took Admiral Jean Francois Darlan, the commander in chief of all French forces, into protective custody. He convinced Darlan to order his troops to cease resistance of the Allies moving into northwest and west Africa.

Clark later reflected on the “bombardment of criticism” he received from the “political wrangling” involved with these efforts:

“There is only one real answer I can give – as Ike’s deputy, I was charged with fighting a war, or more specifically, with preventing a war against the French and getting on as rapidly as humanly possible with the war against the Axis in Tunisia.”

Clark organized and commanded the Fifth Army, which activated in January 1943, in French Morocco. By September, the Fifth Army was transported to Salerno, Italy, and began the advance on Naples. Leading up to the amphibious attack on Anzio, Clark’s troops suffered heavy losses on the Rapido-Garigliano front.

On Jan. 20, the Battle of Cassino commenced, while Allied forces prepared for the landing at Anzio. Clark spent much of his time rotating between both fronts. Roughly 50,000 Soldiers and 5,000 vehicles went ashore at Anzio, about 33 miles from Rome. German strength grew from an initial 34,000 troops to 70,000 in two weeks. Clark said that January through March were the hardest days of battle for the Fifth Army, but the Allies succeeded in gaining a foothold at Anzio and the high ground at Cassino.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt flew to Sicily to personally award Clark with the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions at Anzio.

After weeks of bitter fighting to capture Naples and forcing a German withdrawal, the Fifth Army faced less resistance with the invasion of Rome. When Clark drove with his staff to the gateway of the city, he stopped for a photograph in front of a large sign that read “Roma.” At that moment, shots rang out from a German sniper firing at them from a distance. Bullets hit the sign, but the senior officers were unscathed. On June 4, 1944, Rome was the first Axis capital liberated from the enemy.

With the shift in troop strength moving from Italy to France, Clark found his Fifth Army numbers dwindling. By August, he slowly integrated 25,000 men from the Brazilian Expeditionary Forces into his formation.

In December 1944, Clark was placed in command of the 15th Army Group, which consisted of the Fifth Army and the British Eighth Army, as well as all of the fighting elements in Italy.

By the spring of 1945, the Nazi forces in northern Italy amounted to 25 German and five Italian divisions. Clark saw the necessity of preventing the enemy from withdrawing to the Alps, where they could establish new defensive lines and prolong the war. The objective was to destroy the enemy in the Po Valley. To do that, the Allies would have to capture and hold Mount Belvedere, an obstacle that Fifth Army battalions failed to accomplish in three previous attempts.

Clark was fortunate to have been sent the highly trained Soldiers of the 10th Mountain Division just when he needed fresh troops to clear the objective. Strategists believed it would take weeks to take Riva Ridge and Mount Belvedere, but the 10th Mountain troops proved everyone wrong in only five days.

The final push for the Po River Valley launched on April 14 with infantry, artillery and air support, as the mountain troops pushed through difficult terrain with steep hills to navigate. It would prove to be the bloodiest day of battle for the 10th Mountain Division.

“It wasn’t easy going,” Clark wrote in his memoirs. “The men of the 10th Mountain Division advanced by inches and feet; but by afternoon they had seized the high ground ….”

On April 20, the Soldiers of the 10th broke out of the Apennines and reached the Po Valley. Clark sent Maj. Gen. George Hays, the 10th Mountain Division commander, a congratulatory message for their successful operation.

The 10th Mountain Division made the first Allied crossing of the Po River on April 23 and found little German resistance. Clark and his troops eventually caught up with the 10th and gave them their final mission to cut off the German escape route at the Bremmer Pass.

With the enemy in disarray, negotiations for an armistice commenced. On May 4, a day after Clark’s 49th birthday, he met with the German emissary at his office in Florence to accept the formal surrender of German land troops in Italy. Clark discussed battle tactics with Gen. Fridolin von Senger, who spoke admiringly of the 10th Mountain Division offensive power.

After the war, Clark was assigned as U.S. high commissioner in Austria, and then commander of U.S. Army Ground Forces. A June 24 cover story in “Time” Magazine reported on Clark’s diplomatic efforts to alleviate the suffering of the Austrian people while curbing Russia’s attempts to exploit the newly-liberated country.

The article described Clark as a likeable public figure who uses his personal charm to disarm detractors. The Russians respectfully called him, “The American Eagle,” a nickname bestowed upon Clark by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

In 1947, Clark was named deputy to the U.S. secretary of state and helped to negotiate a treaty for Austria with the Council of Foreign Ministers.

Clark assumed command of the Sixth Army, headquartered at the Presidio of San Francisco, California, on June 19, 1947. He was appointed chief of Army Field Forces at Fort Monroe, Virginia, in September 1949.

In 1952, he commanded all U.S. troops during the Korean War as commander in chief for Far East Command and as U.S. Army Forces commander. Concurrently, he also served as supreme commander of U.N. forces and governor of the Ryukyu Islands.

After signing the armistice that ended the conflict in Korea, Clark relinquished his posts and retired from military service on Oct. 31, 1953.

Following his distinguished military career, Clark served as president of The Citadel in Charleston, South Carolina. During his tenure there, he was appointed to chair a task force from 1954-1955 to investigate U.S. intelligence organizations, including the Central Intelligence Agency.

Clark served as The Citadel president for 12 years before retiring on June 30, 1965, and then became president emeritus of the esteemed military college.

He died at the age of 87 on April 17, 1984, and was buried on the military college campus next to Mark Clark Hall, which was named in his honor.

The facility at Fort Drum formerly known as the Consolidated Soldier and Family Support Center was memorialized in honor of Clark during a grand opening ceremony on Dec. 19, 2002. At the time, the 13-acre building housed 22 different agencies with 484 employees. It included 94 offices and 390 work cubicles, seven conference rooms, two elevators and 771 parking spaces.

(Editor’s Note: Around and About Fort Drum is a monthly series exploring the history of Fort Drum and the names associated with buildings, sites and structures on post. This is the eighth article in the series.)

Social Sharing