FORT DRUM, N.Y. (Jan. 27, 2022) -- On this Holocaust Remembrance Day, the Around and About Fort Drum series features an individual who worked to make sure his community never forgot the atrocities committed by the Nazis against millions of Europeans.

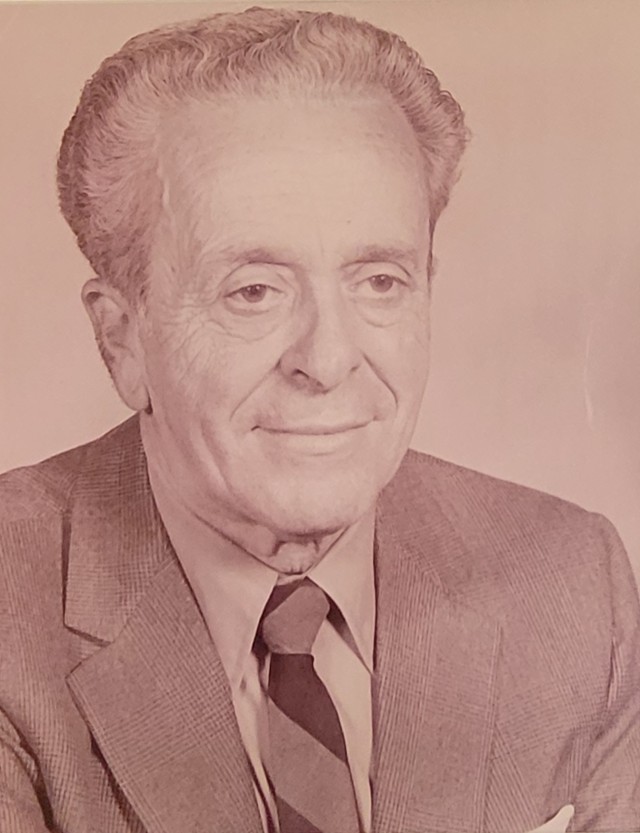

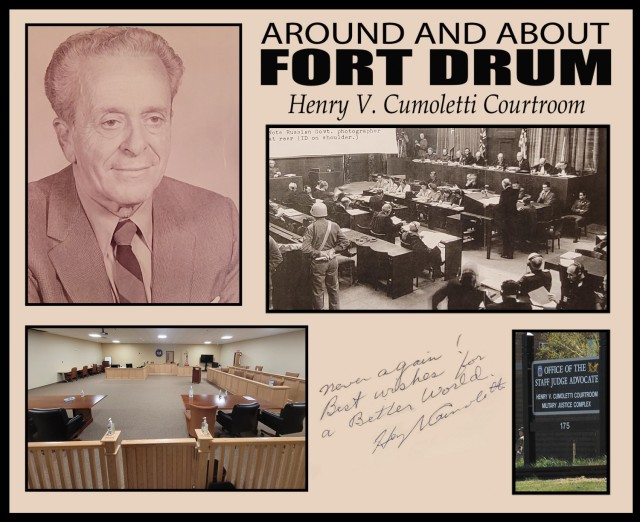

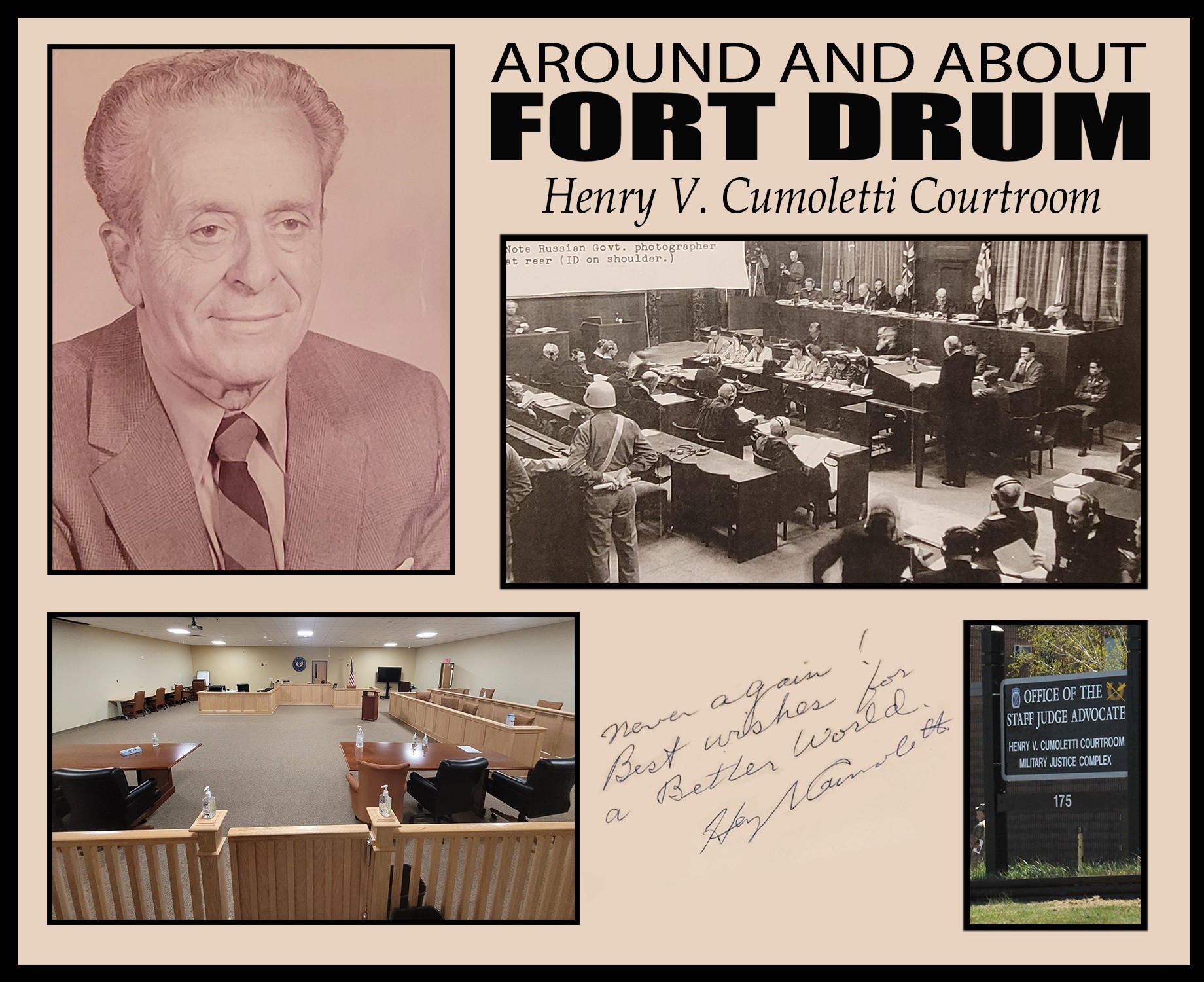

Henry V. Cumoletti, for whom the Fort Drum Office of the Staff Judge Advocate’s courtroom is named, began his civil service career at then Pine Camp in 1941 as an assistant clerk-stenographer. He was promoted to court reporter, and he had worked more than 250 courts-martial when he received a phone call that would forever change his life.

On June 23, 1946, Cumoletti was about to leave his office at the court-martial branch of the Judge Advocate Division for the bus ride to his Watertown home. Then, he was alerted that someone from the War Department in Washington was calling for him.

In a 1991 public broadcast interview, Cumoletti said that the phone call was brief, but it was impactful.

“They just said, ‘Mr. Cumoletti, how would you like to go to Nuremberg?’ And I’m not exaggerating,” he said. “That’s all they asked me. And I was really stunned.”

He, like most Americans, was aware of the Nuremberg War Crime Trials happening halfway around the world, where former Nazi leaders were being prosecuted for crimes against humanity before the International Military Tribunal. The series of 13 trials were the first to have a panel of judges from four countries – the U.S., Soviet Union, France and Great Britain.

Cumoletti said that he was approached with the assignment due to his extensive service with the War Department as court reporter and his work at Pine Camp with German and Italian prisoners of war.

“It was held in Nuremberg because that was the seat of the greatest demonstrations of power held by the Nazis,” Cumoletti said in the television interview. “They held massive demonstrations there, maybe a million people gathered there. The greatest demonstrations of power, and the Allies decided, as a lesson, that was where they were going to have it.”

Three weeks later, he would leave his wife and three children to board an Army transport plane to Europe. For the Brooklyn native, this was his first air flight and his first trip out of New York state.

“And it was generally known that I never cared to go on rides at the carnival,” he said. “I was always afraid of the heights. But when I sat in that airplane, I was very apprehensive.”

The flight was long, with stops in Newfoundland and Paris, France. By the time the plane touched down to its final destination, Cumoletti said he had lost his fear of flying and actually enjoyed it.

He joined a team of court reporters who took testimony in shorthand or typed, in roughly 20-minute relays. When a session was over, the court reporter would re-type the notes so they could be checked with the audio recording of the testimony, and then made into a copy for the official record.

Given a choice of typewriters, Cumoletti selected an Underwood model that reminded him of home. He was also shown how to operate the earphones they wore, allowing court reporters to listen to the translator’s version of whatever language was being spoken during the proceedings.

Taking the second relay on his first day there proved to be a little intimidating for Cumoletti.

“When I got to the second relay, I faced these massive bronze doors with heavy security,” he said. “And the police opened up the doors just so I alone could walk into this courtroom, packed with dignitaries from all over the world, prosecutors and judges and the 21 Nazis sitting right up there.

“It’s difficult to explain the thrill of that, to just walk in there, and the presence of everybody, and the proceedings were going on at the time, by the way, so there was a momentary disruption as everyone looked to see who’s this guy coming in,” he continued. “And you hoped that you don’t drop your pencil or your book or anything else, and you hope you do your job right.”

Until the trials concluded, he spent his days listening, writing, typing … and learning. While digesting overwhelming amounts of information and details of the Holocaust, he was not permitted to speak or offer opinion. He said it was difficult not to be emotionally affected by the sheer amount of evidence presented at the trials.

“It changed my whole philosophy of life and thinking,” Cumoletti said. “I couldn’t believe what I saw. I see this human lampshade, a lamp made from human skin, it’s hard to believe. You say to yourself, is this a new world? What is this all about? A city 95 percent leveled. And here’s the evidence, it’s staggering. You can’t believe that humans would do these things.”

While testifying about an incident where German soldiers killed a group of prisoners to avoid having to feed them, a Nazi officer justified this as a youthful prank.

“The Nazis were tremendous for taking pictures, while these things were occurring, never believing they would lose the war,” Cumoletti said. “And they didn’t have time to destroy them, so the evidence was there, the films were there as people were getting slaughtered. The thing that I didn’t like, the one thing sometimes stands out more than others, is to have these kids in the pit – that’s what bothered me – little children with their mothers, trying to hide under their mothers’ skirts, for example, and have them machine-gunned.”

Sitting 10 feet away from defendants such as Rudolph Hess, Hermann Goering and Albert Speer, Cumoletti could look into their eyes and watch their reactions throughout the trials.

“None of them showed any compassion – they sat there sullen and quiet mostly,” he said. “The seriousness of this thing didn’t come across.”

Hans Frank, the Nazi governor general of Poland, said that if he were to write down all the names of people he was responsible for having killed, all the forests in Poland would not be sufficient to furnish the paper for this list.

“He wrote that in his diary,” Cumoletti said.

Cumoletti could not believe the way Goering kept his composure during the trial, giving no hint that he was prepared to die by suicide instead of accepting a death sentence from the guilty verdict.

“He knows that you’re not going to hang him, because he is going to kill himself,” he said. “He has this plan all the way, and he never displayed any emotion along those lines.”

Cumoletti said that the trials were not limited to convicting only the high-level Nazi leaders, but also a number of other party members, the Gestapo and medical personal. He was asked to remain in Nuremberg for the subsequent trials, but Cumoletti declined.

“I saw enough, I wanted to come home,” he said. “I missed my family.”

His experiences in Nuremberg were never far from his mind, and, for many years after, Cumoletti would lecture for free at schools, universities and civic organizations across the country. He said he felt obliged to share his experiences with others, especially students.

“I was amazed that the schools taught them little if nothing at all on the Holocaust,” he said. “Many of these students were glad to come to the end of the stage and ask me questions about it. They don’t know the words Nuremberg or the Holocaust, and that’s a fact.”

Cumoletti left federal service in 1953, but he continued working as a court reporter for the Watertown City Court. By the time he published his recollections of Nuremberg in the 1989 book “Crimes Against Humanity,” he had delivered more than 300 lectures. On several occasions, Cumoletti spoke with personnel at the Fort Drum Office of the Staff Judge Advocate, and he donated a photograph of the Nuremberg Trials that is still displayed there today.

Cumoletti said he was afraid that future generations would forget what happened, and thus be susceptible to allowing such atrocities to reoccur.

In the preamble of his book, he wrote: “The innocent are always vulnerable, but the ignorant are doomed.”

He also quoted the statement of U.S. Chief of Counsel Robert Jackson, who said at the trial:

“What makes this inquest significant is that these prisoners represent sinister influences that will lurk in the world long after their bodies have returned to dust. They are living symbols of racial hatred, of terrorism and violence and of the arrogance and cruelty of power. They are symbols of fierce nationalism and militarism, of intrigue and war-making, which have embroiled Europe generation after generation, crushing its manhood, destroying its homes and impoverishing its life.”

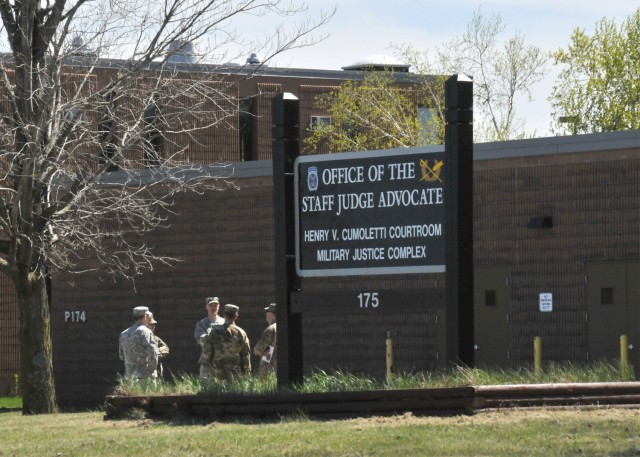

Cumoletti died at the age of 89 on Nov. 6, 1996, in Watertown. Fort Drum officials dedicated a courtroom in his honor, located in a wooden WWII-era building on South Post, in 1997.

Twenty years later, a new courtroom opened on post, and the Henry V. Cumoletti Courtroom was dedicated on May 10, 2016. Three generations of the Cumoletti family attended the event.

Brig. Gen. Charles Pede, who served as commander of the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General Legal Center and School at the time, joined Cumoletti’s son and daughter in the ribbon-cutting ceremony.

“Mr. Cumoletti allowed us to look backwards, and he reminded us constantly of this history that we all share and have to remember,” Pede said.

(Editor’s Note: Henry V. Cumoletti’s book “Crimes Against Humanity” and the WPNE/WNPI Public Television interview (https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn509003) were the main source material for this article.)

Social Sharing