One of the things that makes the United States military so successful is its command structure and its clear line of succession, should a warrior fall in battle. The commander has his executive officer, the sergeant major has his first sergeant, and the platoon leader has his platoon sergeant. Unfortunately, war seldom cares of for such formalities.

So what happens when multiple leaders fall in the chaos of combat? Who takes command if all senior leadership has died? In the case of the 102nd Infantry Regiment during a battle near Verdun, France, on Oct. 27, 1918, the responsibility fell on a young corporal from New Haven, Connecticut.

Timothy Ahearn was born on Dec. 15, 1898. He was the third of six children born to Patrick and Bridget Ahearn, who emigrated from Ireland in 1886 and 1887, respectively. At the age of 18, following his graduation from St. Francis Catholic School, he enlisted in the 26th Regiment as an infantryman with the intent of fighting against Francisco “Pancho” Villa on the Southwest border.

After his service in the Mexican Expedition in November 1916, his unit mustered out of service, but was remobilized in February of the next year after the United States declared war on Germany and re-designated as the Connecticut National Guard’s 102nd Infantry Regiment.

The 102nd rose to quick fame when, on April 20th, 1918, it engaged in the United States’ first major infantry battle of World War I in Seicheprey, France. Despite heavy bombardments and the eventual capture of the town by German forces, the Soldiers of the 102nd never gave up and initiated a counter-attack that regained the lost American trenches.

This was the American’s first encounter with the horrors of trench and chemical warfare. Climbing out from the protection of the trenches and into the maelstrom of enemy fire in the area that became known as “no man’s land” left many soldiers fearful. However, according to a local newspaper, Cpl. Ahearn’s “coolness and courage under fire,” left others surprised and motivated to follow his lead. The article continued: “Ahearn was always in the first when the boys went ‘over the top.’ He seemed to bear a charmed life, and although the boys dropped on all sides of the gallant corporal, he still pressed on …”

His ability to lead those around him would become instrumental in the days following Seicheprey. On Oct. 27, 1918, an enemy attack killed or incapacitated every officer and sergeant in his company. With only 17 able-bodied men still standing, Ahearn did what no corporal probably ever expects to do while in combat: he took command.

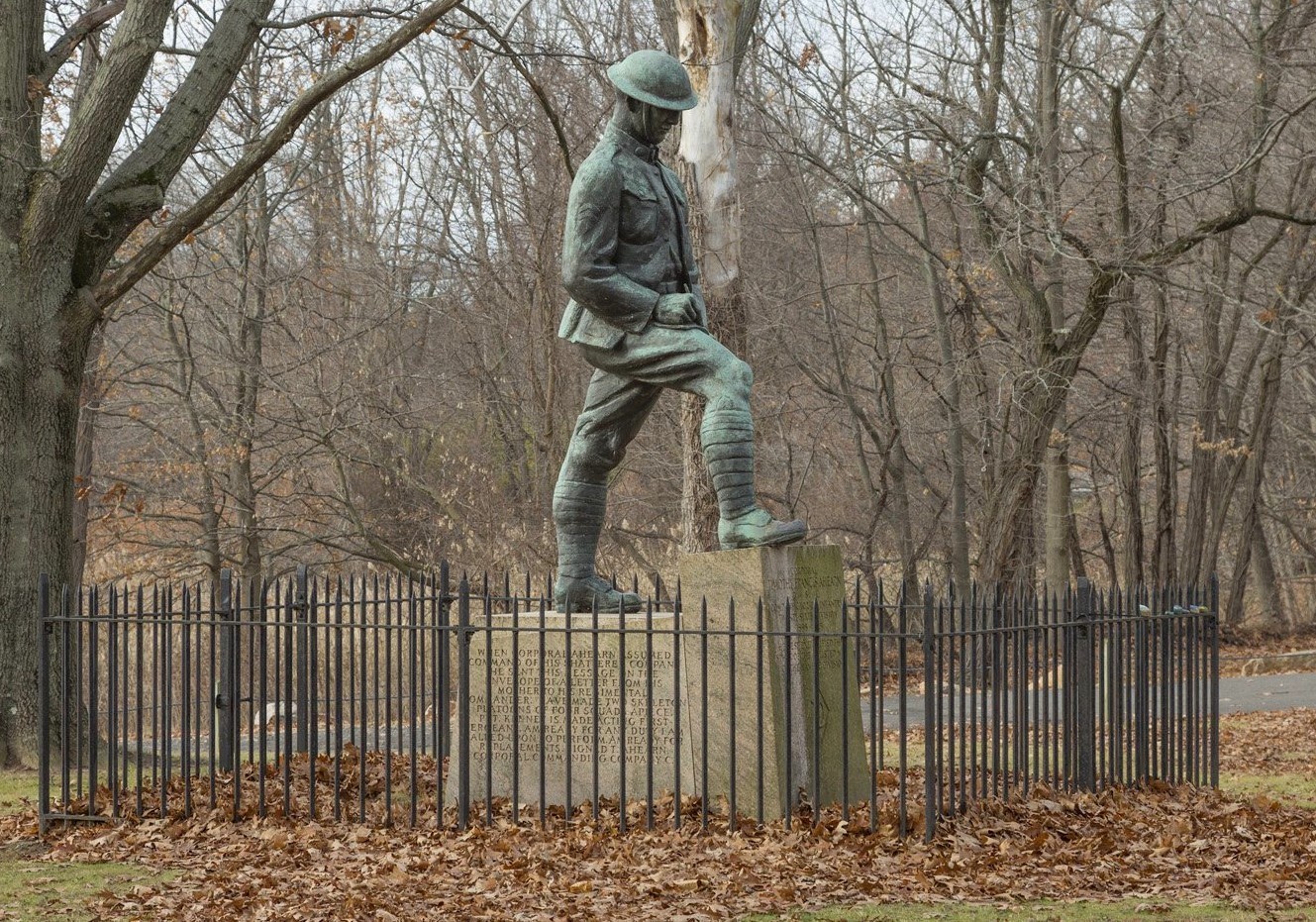

Under his care, the shattered remnants of his unit successfully held the line for the remainder of the battle. Once the bullets and shells stopped firing, Ahearn sent this message to his regimental commander on the back of a letter from his mother: “Have made two skeleton platoons of four squads apiece. Pvt. Kenney is made Acting First Sergeant. Am ready for any duty I am called upon to perform. Am ready for replacements. Signed T. Ahearn, Corporal, commanding Company C.”

In addition to keeping his soldiers focused on keeping the line, he also made at least one trip into no man’s land and, while under heavy machine gun fire, successfully retrieved a wounded soldier from imminent demise. For his gallantry on that fateful day, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the French Croix de Guerre, and the Italian War Cross.

Like so many other young warriors who fought in World War I, when Ahearn returned home, he suffered from the side effects of exposure to chemical weapons. Just three days after his actions in Verdun, he fell victim to an enemy gas attack during the Meuse-Argonne offensive and had to spend some time in an army hospital in Revigny, France. Although he survived the war, his body and mind continued to suffer.

Upon his discharge from the Army, he moved back into his family home with his parents and two of his younger siblings and found work as a stenographer in a local office. In January 1920, the unexpected death of his father Patrick left his family precarious situation. His mother, brother, and sister moved to New York to live with his older sister and her husband, but he decided this was the perfect opportunity to set out on another adventure.

For the next five years, Ahearn wandered the country from coast-to-coast trying to make a living as a migrant worker. On Jan. 25, 1925, Timothy Francis Ahearn passed away in San Francisco from respiratory complications of his exposure to mustard gas. He was 25.

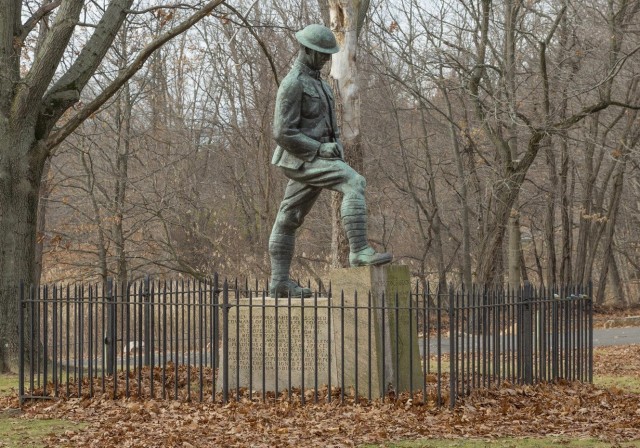

In 1937, the New Haven chapter of the Yankee Division Veterans Association dedicated a statue of Ahearn at the West River Memorial Park where his memory and story will continue to live on.

Social Sharing