PORTLAND, Ore. — Leaves are changing, the weather is cooling and getting wetter, and Fred Meyer is stocking its shelves with Christmas decorations, which means it’s October. Instead of skipping ahead to winter holidays, let’s fall back and celebrate autumn and Halloween by highlighting a fish that has been demonized in the past, partly for its looks, and partly for our past perceptions of it as a blood-sucking, bottom-feeding trash fish*: the Pacific lamprey.

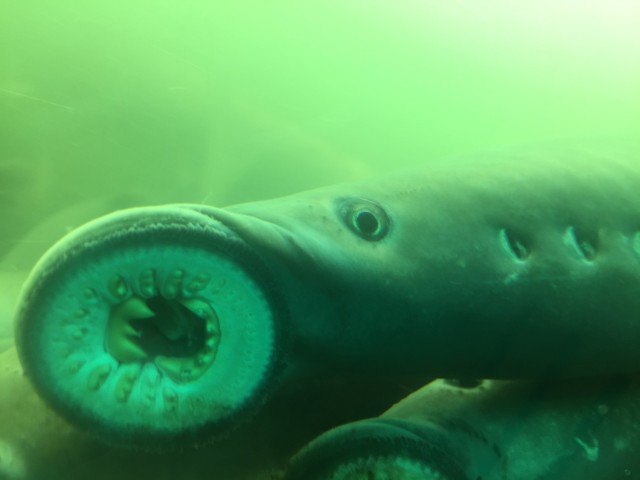

It’s true. This fish from before the time of the dinosaurs is gruesome, scary, nightmare fuel or part of the “Upside Down” in Stranger Things … and because of those things, lamprey were like the Rodney Dangerfield of fish: They don’t get no respect.

That is, until recently.

Some, like Tammy Mackey, Portland District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) Fish Section chief, even find the lamprey species to be “cute and cuddly.”

“I find them fascinating because they are so old and they’re not a detriment to our ecosystem; they’re not like the sea lamprey in the Great Lakes,” said Mackey. “If you take time to really stare into their little, bitty, beady eyes, it’s like you can connect with them,” she said. It’s more like a Valentine’s Day animal than a Halloween animal…they have a lot of depth to them.”

Pacific lamprey are also important to tribes in the Northwest. They have rich, fatty meat, which provides a food source and tribes use them during feasts and celebrations according to the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission’s (CRITFC) website.

“Lamprey are high in vitamins and have medicinal qualities; the oils were and are used for a variety of purposes, such as treating earaches and skin conditions and the oils were also collected and used for lamps,” said Laurie Porter, CRITFC lamprey project lead. “Lamprey have been misunderstood, mislabeled, and attempts were made to eradicate them in the past. The tribes have led the way to change the narrative and were the first to bring attention to the plight of lamprey and have educated the greater community on their cultural and ecological significance,” Porter explained. “They’re native to the area and not an invasive species. If you eat salmon, you should be supportive of lamprey because they bring nutrients to the system – they buffer salmon – a protector of sorts.”

Fresh perspectives and added prominence as a “first food” have helped increase fish managers’ focus on studying and assisting their upstream migrations. For instance, engineers didn’t initially design the fish ladders, which successfully move salmon upstream of the lower Columbia River dams (Bonneville, The Dalles and John Day) with lamprey in mind.

But that’s changing. Andrew Derugin, Supervisory Fish Biologist at Bonneville Lock and Dam, and his team are making improvements for lamprey passage.

“Overall, it’s higher water velocities that are fine for salmonids but are challenging for Pacific lamprey,” said Derugin. “We operationally change water velocity at night to help lamprey enter the ladders,” he said. Additionally, we are making modifications to improve passage including installing resting boxes, climbing ramps, new orifices, rounding challenging corners and other lamprey-friendly actions, he said.

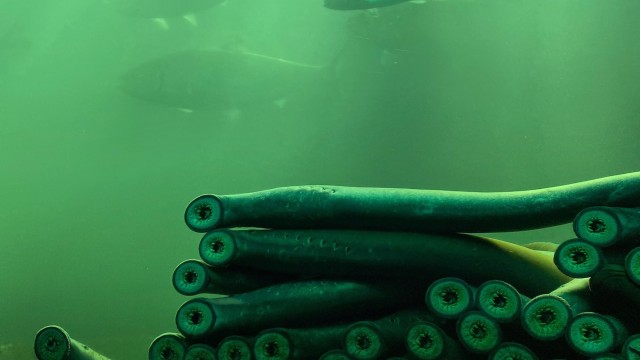

Until Corps engineers and scientists can make improvements at all lower three Columbia dams, CRITFC will help the Corps move lamprey upstream. In fact, CRITFC transported the largest-ever number of lamprey upriver for the Umatilla, Yakama and Nez Perce tribes to release into tributaries in the upper Columbia and Snake River basins in 2021. CRITFC collected and transported 5,714 fish with less than one percent mortality.

“Tribes translocate lamprey into areas that lamprey were known to historically occupy and where they have been extirpated or near extirpated. Sites are carefully selected to ensure the habitat can support the population and to optimize spawning success and larval occupancy and growth,” said Porter. “The Umatilla lead the way with translocation outplanting in 2000, followed by the Nez Perce Tribe and Yakama Nation. Translocation is a stopgap measure to avoid extirpation while improvements to passage are being made. The ultimate goal is for Pacific lamprey to return in sustainable harvestable levels throughout their historical range and in all tribal usual and accustomed places,” Porter continued.

Porter also added that the Warm Springs Tribe doesn’t currently participate in translocation but conducts Research Monitoring and Evaluation for conservation and restoration measures.

In the near-term, it’ll take the Corps four more years to finish planned and funded improvements for lamprey passage, with another year for monitoring and evaluation. Staff will continue to seek improvements and funding in the future. Small but important steps. In the meantime, lamprey can work on their image, too. They have an uphill battle (without a fish ladder, this time) – mainly because they look like a Demogorgon (see Stranger Things).

*“Trash fish” specifically refers to fish that fisherman catch that are undesirable (carp, pikeminnow, etc.).

Social Sharing