CAMP HENRY, Republic of Korea – The puzzled looks and worried questions still come, usually when Master Sgt. Harry Willis III takes an unexpected fall or runs like he’s trotting. There used to be a time where these reactions would bring embarrassment.

“The hardest time for me was understanding the disability and how I can overcome it,” said Willis, who works in the Distribution Management Center, 19th Expeditionary Sustainment Command. “Once I start working through the disability, instead of avoiding it, then I can use that to adapt.”

The reminders of his injury are constant, from a loss of feeling in his toes, to an often unpredictable leg movement. The Purple Heart medal Willis wears on his dress uniform is another reminder of a night in Iraq when everything went dark, and his flourishing Army career was suddenly at a crossroads.

In 2005, nearing the end of his second deployment, Willis was seeing the results of dedicating his 12 months in Iraq to upgrading his physical fitness. Even though Willis was a high-performing wrestler in high school who qualified for the Army Wrestling Team shortly after arriving at Fort Riley, Kansas – on this deployment he took it to another level.

Willis would set personal records on his Army Physical Fitness Test, breaking 11 minutes in the 2-mile run and recording 96 push-ups and 86 sit-ups. Combined with his combat-tested proficiency as a motor transport operator (88M), Willis was promoted to sergeant shortly before his 21st birthday.

On one of the final missions for 2nd Transportation Company, 1st Sustainment Brigade before redeploying, Willis’ convoy driving skills may have saved the life of himself and his platoon leader.

“We were doing retrograde operations, going from Balad to Taji,” said Willis. “Normally, blackouts happen all the time, but this one was different – the whole grid went dark.”

In the middle of a Heavy Expanded Mobility Tactical Truck convoy that was 36 vehicles long, Willis saw fireballs and soon white tracer rounds coming from the tree line. Willis could see the enemy fire was directed at the HEMTT drivers, and turned off his truck’s headlamps in response.

Three .50-caliber rounds hit the cab of the truck, two were low and entered the floorboards, but one partially broke through the armored driver’s door. The fragments of that bullet perforated Willis’ legs, and the bullet tip lodged behind his right knee. A leader’s book in his cargo pocket absorbed some of the bullet fragments.

Willis screamed out that he was hit but – overcome with adrenaline and the intense heat of the fragments – the pain quickly subsided.

“It was so hot that my leg went numb, and I started laughing – thinking I had avoided getting hit,” said Willis, whose relief soon turned to panic when he saw blood pooling out.

Even with his serious wounds, Willis kept driving. Understanding that a sudden stop in the convoy could have jeopardized other trucks, he pushed through until they reached a safe stopping point more than a mile later.

The Long Road Back

After receiving life-saving attention from an Air Force combat medic, Willis’ rehabilitation journey began. His first stop was Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, then Walter Reed Army National Military Medical Center outside Washington, D.C., and finally Brooke Army Medical Center on Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

Before leaving Iraq, Willis was awarded the Purple Heart with his unit and brigade leadership by his side. He remembered learning about the Purple Heart in high school from one of his teachers who received it during the Vietnam War.

“Never in a million years did I think I would earn the Purple Heart,” said Willis.

Throughout his medical travels, Willis endured many surgeries to prevent infections in his wounds, and allow him to someday walk again.

“Reality started to set in,” said Willis, whose weight dropped from 210 pounds to 160 in the weeks after the attack. “The same legs that got me a 10:38 2-mile now just don’t work.”

Reality also meant a rehabilitation that depended just as much on Willis’ perseverance than medical treatment. At first, Willis had little interest in eating, much less rehab. A medical discharge from the Army was one possibility, but Willis was determined to continue his service as a young NCO.

One of his doctors at BAMC could see the potential Willis still held as an NCO, and one day gave him a wake-up call that would start his road back to walking and running.

“He said to me ‘are you going to let this define you? You say you want to stay in, but you’re not showing progress.’” said Willis. “That’s when I got off the pity wagon.”

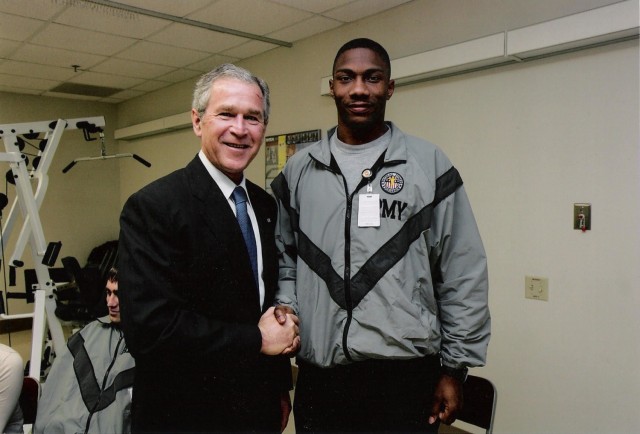

With a newfound urgency, Willis went from bed-ridden, to a walker, to a walker with wheels, to walking with a cane in a matter of months. His rehabilitation at BAMC also included a visit from President George W. Bush, who chatted candidly with Willis and encouraged his recovery.

Even though he still could not wiggle his toes, Willis had started to adapt to his injuries and get back into physical fitness. While his days of running a 10:38 2-mile were probably behind him for good, his time of “only” 13 minutes was still far above average.

By 2007 he was deploying with 1st Sustainment Brigade, 1st Infantry Division again, and this time he brought a new outlook on leadership. Willis recalls once feeling indifferent to the frequent combat convoy training that focused on safely egressing after a rollover.

“In 2012, my convoy got hit with a 700-pound bomb, and I started calmly directing everyone on their roles,” said Willis. “It reminded me, this is why we do so much training.”

Willis has used his combat experience to help teach the next generation of Army transporters, first as an instructor at the Army Transportation School, and now at the DMC where he helps coordinate all military transportation throughout Korea, as the Transportation Operations Branch NCOIC.

Since 2012, Willis has been active member of the Sergeant Audie Murphy Club, a volunteer organization that promotes excellence in the noncommissioned officer corps. Willis brought his passion for SAMC to Korea, where he helped revive the Area IV chapter.

“It didn’t really take off until he came, he’s been carrying the torch,” said Sgt. Maj. Andy Lee Hardy, DMC Sergeant Major. “His accomplishments are a testament to his leadership.”

While at DMC, Willis also assisted Hardy in mentoring Soldiers who attend the Basic Leader’s Course on Camp Henry.

Though his career has since accelerated and his body has recovered, Willis never forgets the pain and journey from that night in September 2005.

Social Sharing