Intriguingly, the truck-mounted MGR-1 ‘Honest John’, the United States’ first surface-to-surface nuclear-capable missile, was developed at Redstone Arsenal in 1951, and thus could theoretically have been what the soldiers saw. But Heidner says the system didn’t come to Yuma for testing until 1958, the year after the Soviet Union proved it possessed intercontinental missile capability by launching Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite.

“White Sands Missile Range was really busy in a post-Sputnik spasm, so some of the hiccups with Little John and Honest John were tested here,” said Heidner. “It resulted in many upgrades like telemetry and cinetheodolites and a lot of range improvements. We didn’t really have the instrumentation to accommodate missile testing prior to that: YPG was mainly a tube-launched projectile kind of place.” VIEW ORIGINAL

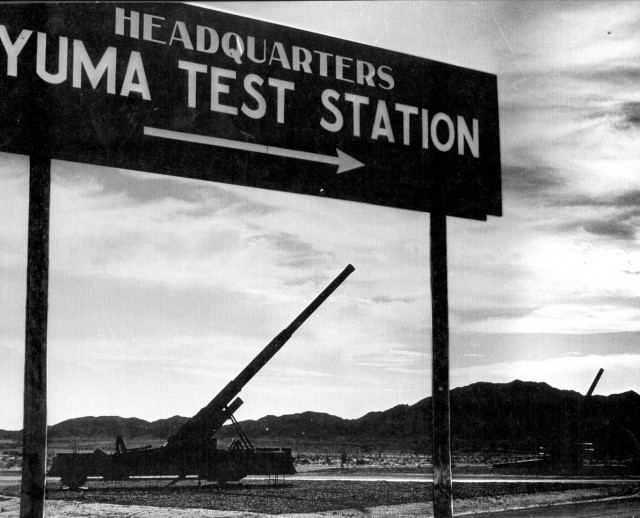

From its inception as Yuma Test Station in 1951, U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground has been a natural desert laboratory for testing equipment destined for use by Soldiers.

It is a place where the scientific method trumps superstition and wild speculation, where unexplained phenomenon are methodically identified and fixed.

Yet, at least once in the proving ground’s distant past, personnel viewed something in the sky that was never definitively explained.

It was a bit after 3:00 in the afternoon of Thursday, April 17, 1952, and 13 Soldiers were in the midst of a field familiarization hike three miles south of Yuma Test Station, near what today is a vehicle mud course. We can’t say with certainty what the temperature was that afternoon—YPG’s weather records only go back to 1956—but presumably it was warm enough for the men to enjoy resting beneath a shade tree in between a canal bank and the Colorado River. Suddenly, they saw almost directly overhead a flat-white circular object heading toward the mountain-lined southeastern horizon, emitting an intermittent vapor trail. About a quarter inch wide when judged at arm’s length from the ground, the object disappeared within seven seconds.

Official records of the U.S. Air Force from the 1950s and 1960s are replete with such sightings. Often, the objects were weather balloons or extremely high altitude aircraft like the U2 reconnaissance plane. A scattering of military observers in the early 1950s speculated that such sightings could be unarmed intercontinental ballistic missiles being test fired from the Soviet Union, and duly shared their concerns with agencies like the FBI.

Yet the first flight of the U2 wasn’t until August 1, 1955. Historical accounts of missile development show neither the US nor the USSR had intercontinental missile capability until later in the 1950s. And all 13 Soldiers who saw the object at Yuma Test Station that day in 1952 were part of the post’s meteorology team, men who knew full well the look and flight characteristics of weather balloons.

“I have 11 years military duty in meteorology, with a substantial portion employed on weather equipment development and upper air observations entailing the use of many sizes and types of meteorological balloons,” wrote 2nd Lt. Bernard Gudenkauf in his report on the incident. “I have never observed any other object with which this object could be identified.”

Standing under the shade tree looking at the horizon where the object had disappeared, Gudenkauf told the Soldiers they should attempt to take a bearing on it from at least two theodolite positions if they ever saw the object again. The following day, two of the men, both of whom had engineering degrees, had just that opportunity, and this time they had a theodolite within their reach. Yet the object’s flight pattern was so fast and erratic they were unable to take a reading. It left no vapor trail this time, and vanished across the horizon within 10 seconds.

At the time, the Yuma Test Station headquarters staff relayed information of the sighting to their superior command, the Sixth Army, who in turn forwarded it to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. Beyond a request for a written report about the sighting from the officer who witnessed it, there is no further documentation regarding the sighting or speculation as to its origin within the long-since declassified files.

Modern day members of YPG’s meteorology team doubt that the object had extraterrestrial origin. In fact, they are skeptical it originated from anywhere outside the boundaries of Yuma Test Station.

“I hope they fully understood the behavior of weather balloons,” said Nick McColl, the present-day chief of YPG’s meteorology team. “This thing was moving awfully fast for a weather balloon, even if it were in a low-level jet stream.”

By 1952, meteorology had come a long way since the invention of the radiosonde in the 1920s and the advent of radar during World War II, but was still far less sophisticated than today. The first meteorological satellite, for example, was nearly a decade in the future from that long-ago spring day. It is unlikely that any of the enlisted men who witnessed the object had meteorology backgrounds prior to their time in the military. Likewise, on-post communication was far less integrated in the early days of Yuma Test Station. According to YPG Heritage Center curator Bill Heidner, when the test station was re-opened in 1951, six different test activities reported back to separate home stations across the United States. They didn’t share range space, and rarely discussed aspects of their respective test missions with one another.

Intriguingly, the truck-mounted MGR-1 ‘Honest John’, the United States’ first surface-to-surface nuclear-capable missile, was developed at Redstone Arsenal in 1951, and thus could theoretically have been what the Soldiers saw. But Heidner says the system didn’t come to Yuma for testing until 1958, the year after the Soviet Union proved it possessed intercontinental missile capability by launching Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite.

“White Sands Missile Range was really busy in a post-Sputnik spasm, so some of the hiccups with Little John and Honest John were tested here,” said Heidner. “It resulted in many upgrades like telemetry and cinetheodolites and a lot of range improvements. We didn’t really have the instrumentation to accommodate missile testing prior to that: YPG was mainly a tube-launched projectile kind of place.”

The sightings, it should be noted, coincided with the annual Lyrid meteor shower, which, while not prolific, has a higher likelihood of producing brilliant fireballs that can hiss through the air and throw shadows on the ground in daytime.

So, what did the Met team Soldiers of 1952 see in the skies all those Aprils ago? Meteors? Artillery shells? Missiles? Airplanes? Was it a case of bored Soldiers far from the frontlines of raging combat in Korea inventing a good story? Or a sighting of a high-performance spacecraft from beyond our planet piloted by intelligent beings?

Any of these are possible, but the last is certainly the least likely.

Social Sharing